Meeting Juma Al Majid takes you back to the very roots of Dubai and to the heart of its history and culture.

He was born into a family of pearlers and fishermen in Shindaga, on the banks of Dubai Creek. As a young boy, Juma used to accompany his father on long, arduous trips at sea.

It was there he learnt patience and perseverance, two qualities that buttress his life-long pursuit of promoting education and preserving the cultural heritage of Emiratis – and that of the larger Arab and Islamic world.

He learnt too under the tutelage of teachers such as Farah Al Quraini and Ahmad Al Qanbari before he formally joined the National School in 1948, the Dubai institution founded by Hassan Mirza Sayegh.

But trading was in his blood, and after leaving school he began life as a trader, setting up an enterprise that would eventually become the Juma Al Majid Group – a thriving and multi-faceted business that is prominent now in the UAE and beyond.

Despite his professional career, education and culture remained close to Al Majid’s heart. In the early 1950s he and a few fellow businessmen, with the consent of the late Shaikh Rashed Bin Saeed Al Maktoum, established secondary schools for boys and girls as well as the first charitable society to help the needy of Dubai.

In 1986, he also established the Arab and Islamic Studies College.

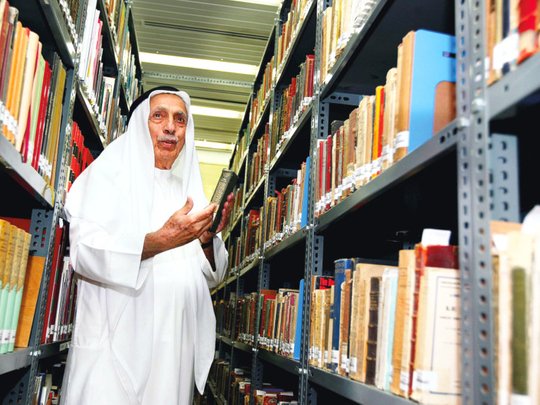

Throughout, however, Al Majid’s enduring love for books now defines one of his most significant contributions to the world.

In 1991, he established a public library to meet the needs of researchers and scholars as a reference point for books, writings and manuscripts.

Indeed, that library has now grown and expanded, becoming a cultural organisation that bears his name – The Juma Al Majid Center for Culture and Heritage. To this day, it remains a pre-eminent centre of learning, history, literature, culture, education, heritage and social interaction and exchanges in Dubai and the UAE.

Al Majid was one of the first businessmen in the UAE to donate money, time and resources into the service of books and manuscripts, determined to ensure the rich literary heritage of the Arab, Islamic and broader world would be preserved for future generations.

“I consider myself responsible for saving any book that is damaged anywhere in the world,” he says. It’s a commitment and passion that still endures now and drives him forward.

Al Majid, accompanied by specialists from the culture and heritage centre, have scoured the world for Arab and Islamic manuscripts, either originals and copies.

Restoration work

What’s become clear, however, is the need for the latest restorative techniques and innovative technology to ensure the written words of the past survive now and into the future.

The centre subsequently developed the Al Majid restoration machine, which restores damaged manuscripts to a virtually original condition and protects them from further corrosion and decay.

Up to now, the machines have been distributed as gifts to literary restoration centres in more than 14 countries.

To date, the Juma Al Majid Center for Culture and Heritage has received books and manuscripts from institutions as diverse as Harvard University, Sharjah’s National Theatre Library and Mitsubishi, and it has thousands of manuscripts from across the globe that are now preserved in digital form.

The centre attracts a broad range of support, and those associated with its work include Abdulla Abdul Majid, Salim Al Zarkali, Afif Bahnasi, Jamil Salibia, Abdel Rahman Attieh, Hamad Bouchehab, Dr. Abdullah Al-Jubouri, Haitham Al Kilani, and Sidqi Ismail among others.

Al Majid, however, remains a man of vision, enterprise and drive and is a guiding light and inspirational force behind Dubai’s cultural development.

His passion and commitment to preserving literature and works have garnered him many awards including the King Faisal International Prize for Service of Islam (1990); the International Personality Award for Culture and Heritage Service from the Egyptian President (2000); the Cultural Personality of the Year Award at the Qareen Cultural Festival in Kuwait (2005); Tarem Omran Cultural Award for Enterprise (2007); and Sultan Bin Ali Al Owais Cultural Award for Cultural and Scientific Achievement in 2006-2007.

Juma Al Majid speaks with Weekend Review:

We live in an age of barbarism and extremism. How do you think cultural centres such as the Juma Al Majid Center for Culture and Heritage can contribute to the process of enlightenment and the dissemination of culture, science and knowledge among youth?

I do not think that one organisation can change the world, but institutions like ours can help contribute towards better understanding.

Our centre is different from many others because we create, invent, and reach out to all. If researchers and authors cannot come to us, we go to them. Our manuscripts belong to people.

We are different from libraries, not only in the Arab world but in the Western world too.

To help scholars, we keep the costs low by offering digital snapshots of manuscripts and books at one-fourth the price the prevailing price.

We’ve turned the fee system for knowledge on its head.

As the largest manuscript preservation centre in the world, we have a huge collection of very rare written material on various mediums.

There are about 900,000 manuscripts in our center. Few libraries in the world that can match that.

Although we conserve four or five manuscripts a year, it is not our specialty. These manuscripts are not just for preservation and exhibition, but are valuable source materials for readers, researchers and scholars.

Is culture capable of overcoming the challenge of extremists in our time?

It’s a fact that it’s the countries that claim to be civilised that have created extremism and terrorism.

As long as there are presidents and leaders who lie to their people, what can we say? When they investigate, they protect themselves. Tony Blair in Britain admitting his mistake was aimed at avoiding prosecution in the future.

I ask, who created extremism?

See what Bill Clinton said? He said: “We created Daesh.”

People read but do not understand, and do not seem to hear when a head of state says something.

The question is: Why did they create Daesh? To devastate the countries of the world. They are a curse. We must serve culture in order to enlighten the nation, as well as other people.

I’m sure you had read how the government of Japan extended a railway line to a remote village so a girl living with her family on a farm who could go to school. Arab and Muslim rulers should spend at least 10 per cent of their national income on education and 10 per cent on health.

No one wants to hear this, but our situation is catastrophic. Unesco has reported that there are some 80 million illiterate people living now in Arab countries, the majority of them in Egypt.

How have the rulers moved to address this issue of illiteracy in the Arab world?

“We note that some individuals and institutions are doing this. We should not only look at the United Arab Emirates and what Sultan Bin Al Owais, Juma Al Majid or others do in this field, and the facilities and support they receive from the state.

"The late Shaikh Zayed Bin Sultan Al Nahyan, may God bless his soul, and Shaikh Hamdan Bin Zayed Al Nahyan ordered the shipping of all my books and manuscripts in diplomatic bags so as to ensure their safety. His Highness Shaikh Mohammad Bin Rashid Al Maktoum ordered that no book that came to Juma Al Majid Center be subjected to censorship."

When the noted poet Nizar Qabbani came to Dubai to receive the Sultan Al Owais Award, Mr Al Owais said to him: “Go and see the library of the Juma Al Majid Center.”

Qabbani said: “I’ve seen the best libraries of the world, so I don’t need to see it.”

But the scholar changed his mind and came to visit the library. We had coffee and went down to the collection. When he saw the library, he said “I hope my books will also be here.”

I said: “Why not?”

Not believing what he heard, he replied, “But my books are forbidden.”

I said, “No, your books are not forbidden here, as are many others.” Still unsure, he said, “Don’t send anyone to take my books, I will send them to you.”

On his return to Lebanon, the illustrious writer shipped a collection of his books, which we received at the airport and included in our Centre’s collection.

This is the story of our association with poet Nizar Qabbani, one of the most influential voices in the history of Arabic literature.

Why don’t other Arab countries follow the example of the UAE?

Even our neighbours do not seem to want to benefit from our experience.

How old were you when you realised your passion for books? Were you interested in diving and pearling in your younger days?

I do not have even a primary education certificate, but I was eager to provide readers and researchers with books.

I grew up in a poor family and I used to go with my dad to dive for pearls, the hardest career in life. Each one on the ship had his own task.

I do not have even a primary education certificate, but I was eager to provide readers and researchers with books. I grew up in a poor family and I used to go with my dad to dive for pearls, the hardest career in life. Each one on the ship had his own task.

It was my responsibility to take care of Al karat, a kind of tree bark from Oman that divers use to cover their bodies to protect them from sores and the effects of salt.

I grew up in a poor family and I used to go with my dad to dive for pearls, the hardest career in life. Each one on the ship had his own task. It was my responsibility to take care of Al karat, a kind of tree bark from Oman that divers use to cover their bodies to protect them from sores and the effects of salt

Pearl farming here is about 120 years old. After the first World War, the price of pearls fell and European countries and the United States no longer bought pearls from us – although India with its kings and merchants continued to buy from us.

Before the Second World War, prices went up again, but only to drop again and the Gulf was broke.

A merchant would invest Dh10,000 but only earn Dh6,000. Majid Al Ghurair had the largest ship those days and returned with 100,000 bags at a time.

Smaller boats were no match for such production, at best producing 20 or 30 bags, sometimes 100 bags of seashells, clams and oysters.

You are one of the first to link culture and trade in a positive and beneficial manner to disadvantaged segments of society. You enabled these people to access education and contribute to nation building. Do you think Arab capital is still far from being of benefit and service to educational and cultural causes?

Arab and Islamic governments do not spend enough on education, even though we know that only education can save a nation, whether in the Orient or in the Maghreb, Indonesia or Malaysia.

But what can a trader do in this field? All the Arab traders do not equal one trader in America, where there are companies bigger than a state. Even our writers, like parrots, repeat words that were said before a hundred times, and they exaggerate our capabilities because we have oil. We have magnified ourselves beyond all reality.

When it comes to society, I’d say first focus on women’s education.

In our college, we had 2,700 women studying, tuition is free, books are free, transportation is free, and the poor among them even got Dh500 as a stipend.

Most were from the Sultanate of Oman, young women who could not afford private colleges and universities. We focused on the Arabic language, because it is the language of the Quran, and the language of our religion. Our colleges are recognised by Al Azhar of Egypt and the UAE Ministry of Higher Education.

The first master’s and doctorates in the state graduated from our college. I taught women, and when they graduated they found work immediately, and then they got married.

Education is a value that cannot be equated to any fortune in the world.

As a philanthropist, you have come a long way in the field of charity work and social welfare. How would you rate the extent of your influence on culture and education?

Let me tell you this story. When oil fell sharply some 30 years ago, the Gulf states met and decided they could not provide subsidised education to children of expats any longer. I was the head of the parents’ council in Dubai at that time. We had a minister who was president, and I was the vice-president, of Emirates Bank.

I asked him how was it that such a harsh decision was announced just as the new academic school year was beginning? He shrugged and said it was a decision taken by the Gulf Cooperation Council and could do nothing about it.

Where will the children go in these circumstances?

I then called the Minister of Education and asked him if I could have access to state school buildings in the afternoons, after the regular school hours. He said yes. Then I asked for books. He took out a directive from the Prime Minister to give us the books. I told him I wanted teachers, but we would pay them. He agreed to it.

Thanks to Ahmad Al Tayer, the charity schools began. These are things nobody knows. No writers want to write and no newspapers want to publish about such positive developments.

Now we have 12,000 students graduate from charity schools, and they are always among the top ten in the state.

At first it was free of charge, but the success of the schools found other more affluent people approach us for admission to their children. They wanted it because the schools were recognised by the ministries.

We prescribed a fee of Dh5,000 a year, and raised it to Dh7,000 dirhams later. Our students entered many universities and succeeded – they were given their lives.

What is your view on the state of intellectual and cultural institutions in the Arab world at present?

Before 2008, some banks and big companies came to me, to ask what is the secret of the UAE? What is the secret of the revolution you are witnessing?

I told them that here you are free in your mind and in your possessions. Here things are easy, you want to establish a company or build a hotel, school, hospital, or bar, no one is an obstacle to your ambition or investment.

We are working for the common good of mankind.

Do you support the establishment of other cultural centers like the Juma Al Majid Center for Culture and Heritage?

We do not want centres, we want to take people out of illiteracy. We want schools – but adequate good teachers are not available in Arab countries. Take Egypt, where a teacher’s average salary was just 2,000 Egyptian pounds in the days of Hosni Mubarak. So how does the field of education develop?

Do you think that cultural work is still lacking funding from the businessmen in the Arab world?

It’s not cause for the rich alone. Where is the harm if traders contribute 5 per cent of their income, especially since taxes do not exist in the UAE? We must have goals to serve and benefit humanity.

Do you cooperate with global cultural centres, and what are the benefits of such intellectual and cultural exchanges?

Of course, we have a great deal of cooperation with other global centres. If we are asked for a book not available in our libraries, we try to get it from the US Library of Congress, from Bristol or Berlin. We subsidise the costs involved. It is unique work.

Although there non-profit organisations in the world that charge fees, I firmly believe that knowledge should not be for sale or purchase.

Many countries, such as China, Japan and Malaysia invest a lot in education, which is missing in our part of the world. That’s why I insist that at least 10 per cent of national incomes must be spent on education and 10 per cent on health.

What projects are you working on outside the Arab world?

We seek to collect diaspora books from Iraqi, Syrian, Egyptian and other Arab authors, and are seeking to build a library costing $30 million. It will be a charity for the benefit for mankind.

I have always been passionate about collecting books from around the world, and I ask the academics, scientists and researchers I meet to contribute good books to my library.

I am a merchant and I do not have knowledge of all the good books in the world.

We have a Persian library containing about 100,000 manuscripts, and this is part of our interest in non-Arabic literature as well.

I consider myself responsible for saving the books of the world, be it Islamic, Buddhist, Christian, Jewish or any other. They are ultimately the property of humanity as a whole and must be saved, wherever it may be. The pillaging and burning of books is a crime akin to killing the soul. It doesn’t matter where it happens in the world.

What is your view on the happenings across the Arab world, especially the destruction of culture, knowledge and heritage, such as the bombing of the Mosul Library and the burning the Baghdad National Library?

I consider myself responsible for saving the books of the world, be it Islamic, Buddhist, Christian, Jewish or any other. They are ultimately the property of humanity as a whole and must be saved, wherever it may be. The pillaging and burning of books is a crime akin to killing the soul. It doesn’t matter where it happens in the world.

What are your plans for upgrading your cultural, intellectual and educational institutions?

Our projects do not stop, and have no end. I know where I am going and what my world is – books, manuscripts, documents, scholars, intellectuals. It’s all about education, charity and institutions like colleges and schools, the Beit Al Khair Society, the Juma Al Majid Center and others.

The Arab League has chosen our Centre as the best library in the Arab world, and this was announced in Cairo. The Bait Al Khair Association received an award from 76 charitable societies. This is a source of great pride.

In 2013, we established a project to teach girl students free two-year courses in Arabic and English, computers and accounting. Many of them have since found employment after completing their graduation.

Unfortunately, though, I’m afraid while the rest of the world is developing, we have not kept pace.

Many years ago when I first visited South Korea as a trader, I found most people lived in homes that were no more than small nests. They did not have five-star hotels at that time. Now see how South Korea has evolved? The main reason for their development is their focus on education. The Arab world at large is still suffering from an education crisis.

Have you thought of writing your memoirs? Is there such a project?

Inshallah.

Shakir Noor is a Professor of Media Studies based in Dubai and is from Iraq.