You lower a record player’s stylus onto an LP, and it begins. The crackle of needle on vinyl is silenced by a long, low heartbeat fading in and then a maelstrom of sound that serves as overture for the (dis) passion play to come.

Perhaps the record player is illuminated by the light of the nearby lava lamp your sister gave you when she left for college. The maelstrom builds and swirls like the Aleph in that Borges short story your hip English teacher assigned the class, and then — whammo — the album’s soundscape widens into 3D Technicolor CinemaScope, and a weary singer arrives to remind you to ‘Breathe ... Breathe in the air’.

It’s 1973, you’re 15 years old, and you’re listening to ‘The Dark Side of the Moon’.

Well, maybe you weren’t, but I was, and so was everyone my age — an entire generational cohort of suburban adolescents, mostly male, mostly White, for whom Pink Floyd’s album served as a sonic bellwether of our discontent. This year marks the 50th anniversary of the release of ‘The Dark Side of the Moon’ — if it hasn’t aged, neither have we — and this month sees the limited theatrical release of ‘Have You Got It Yet? The Story of Syd Barrett and Pink Floyd’, a long-in-the-works documentary directed by Roddy Bogawa and the late graphic designer Storm Thorgerson, whose cover art for ‘Dark Side’ — a prism blasting colour into the night — is as enigmatic as anything in the grooves of the album itself.

These milestones are convenient excuses to commemorate a work of popular culture that stubbornly refuses to go away. With its clanging alarm clocks and stately dirges, its banshees and its bliss, ‘The Dark Side of the Moon’ is a monolith of Classic Rock, a genre better known to our children and grandchildren as Dad Rock, which they either quickly flip past on Sirius Radio or settle into with studious teenage curiosity, the way I once listened to my mother’s Sinatra records. But here’s the catch — ‘Dark Side’ doesn’t need Sirius or a parental playlist to be discovered by 21st-century adolescents. They find it on their own, right around the time their disenchantment with an adult world they’re being frogmarched toward crystallises into exhaustion.

I played a lot of music when my two kids were growing up at the turn of the millennium, but not a lot of Floyd. And yet at a certain point in their respective teenage individuations, there ‘The Dark Side of the Moon’ was, handed along by friends.

It’s an intriguing conundrum. There are other monoliths of early ‘70s Dad Rock — ‘Who’s Next’, ‘Led Zeppelin IV’, ‘Layla’, ‘Eat a Peach’, insert your own candidate here — so why has this one had such an insanely long tail? 'Dark Side' is the fourth-best-selling album of all time, starting with an uninterrupted run of 14 years on the Billboard 200 and regular appearances up to and including 2023, for a total of 981 weeks on the charts.

It’s not like the world was waiting to pounce on a new Pink Floyd album a half-century ago. ‘The Dark Side of the Moon’ caught everyone by surprise, musically and commercially, especially in America, where the British band’s experimental art-rock had been ignored in favour of stateside sonic explorers like the Grateful Dead.

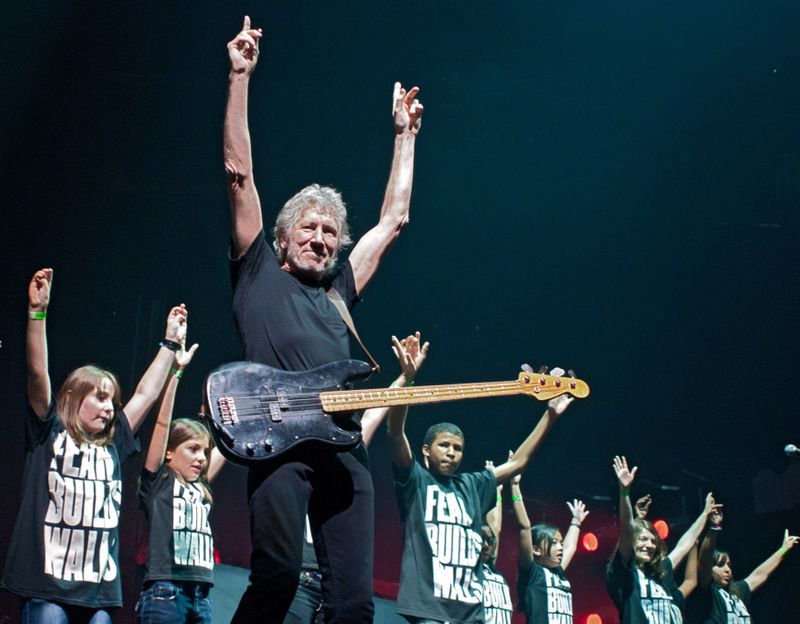

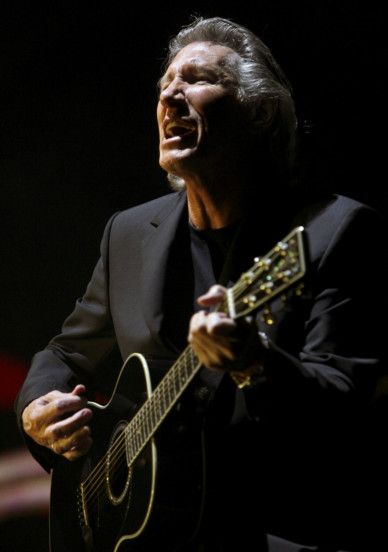

‘Dark Side’ represented the culmination of the group’s struggle to extricate itself from the long shadow of original leader Syd Barrett. As the new documentary makes clear, The Pink Floyd (as they were originally called, fusing the names of Barrett’s favourite American blues musicians, Pink Anderson and Floyd Council) was very much a product of Barrett’s visionary whimsy, with bassist Roger Waters, keyboardist Rick Wright and drummer Nick Mason supporting the leader’s singing, songwriting and lead guitar. The magic lasted through the group’s eclectic first singles, but as early as the tour for the 1967 debut album ‘The Piper at the Gates of Dawn’, a mentally ill Barrett was staring into the middle distance and playing one note for entire sets. He was barely present on the follow-up, ‘A Saucerful of Secrets’ (1968), and got jettisoned from the band shortly thereafter, with guitarist Dave Gilmour already drafted to take his place. Fellow musician John Etheridge later remembered thinking that Gilmour should “enjoy it while it lasts, because without Syd that band’s going nowhere” — one of the great wrong calls in the history of popular music.

But it certainly looked that way after the strained noise-rock half of ‘Ummagumma’ (1969), although the first two sides of that double album conveyed the band’s live power. By 1970s ‘Atom Heart Mother’, you could hear Waters, Wright and Gilmour back off from the hyperactive inventiveness bequeathed them by Barrett and start to assemble a sound we now recognise as Floydian, and 1971’s underrated ‘Meddle’, with its sidelong masterpiece ‘Echoes’, set the stage for the majestic aural cohesiveness of ‘Dark Side’. ‘Echoes’ was rock, it was a trip, but it was somehow pop, too. All that was missing was for Pink Floyd to mean something.

With ‘The Dark Side of the Moon’, they meant something, and in a way that many young American listeners in 1973 intuitively understood.

The Watergate scandal was a spreading stain leading to the door of the Oval Office; US military involvement in Vietnam had ceased in January but the bombing of Cambodia continued for months. The movie theatres were dominated by parables of corruption (‘The Godfather’ won a best picture Oscar the same month that ‘Dark Side’ was released) and demonic possession (‘The Exorcist’ was out by the end of the year). Your parents watched ‘The Waltons’ on TV and wondered what had happened to this country. If you were a teenager, you didn’t join protest marches like your older siblings; you’d missed the revolution and Woodstock, and, anyway, what did protesting get you other than a Nixon landslide? Instead, you hung out with your friends at this new place called the mall. “I’d love to change the world,” the British band Ten Years After had sung a year or so earlier, “But I don’t know what to do/So I’ll leave it up to you.” A lot of us knew exactly how that felt.

So, apparently, did Pink Floyd. ‘The Dark Side of the Moon’ was lyricist Roger Waters’ attempt to catalogue the strains and enervations of the rock musician’s life and in doing so he solemnified and romanticised a generation’s sense of defeat. The drag of an after-school job: “Dig that hole, forget the sun/And when at last the work is done/Don’t sit down it’s time to dig another one.” The deadening IV drip of teenage existence: “Kicking around on a piece of the ground in your hometown/Waiting for someone or something to show you the way.” The sense that the future was more of the same: “Up (up ... up ... up ...) and down (down ... down ... down ...)/But in the end it’s only round and round.” The steady beat of the songs, Gilmour’s mournfully chiming guitars, and Wright’s piled-up clouds of synthesizers left a listener comfortably numb, unprepared for the plane-crash paranoia of “On the Run,” singer Clare Torry’s wordless wails of despair on “The Great Gig in the Sky,” or the 7/4 snarl of ‘Money’.

Among other things, ‘The Dark Side of the Moon’ showed Pink Floyd give up exorcising the living ghost of Barrett and start mythologising him instead on the album’s penultimate track, ‘Brain Damage’ (and on ‘Shine On, You Crazy Diamond’, from the band’s 1975 follow-up ‘Wish You Were Here’). “The lunatic is in my head,” Waters sang in ‘Brain Damage’; a lot of us thought we knew how that felt, too.

Such were the emotions and pretensions of middle-class teenage existentialism in the suburbs of mid-1970s America. ‘The Dark Side of the Moon’ gave them a soundtrack to nod and nod out to and, if you lived near a city with a planetarium, a laser show to light up the dark side of your brain. In three years, punk would come along to obliterate the glorious self-pity of ‘Dark Side’ and insist that there was no future but the one you made for yourself. By that time, a lot of us were moving on and either finding a purpose or letting a purpose find us. Pink Floyd got rich, turned ambitious, splintered into acrimony.

Syd Barrett died of pancreatic cancer in 2006, having retreated from public life to his mother’s house and the eternal mystique that comes with being Classic Rock’s most unknowable lost boy. But ‘The Dark Side of the Moon’ remains a quintessential adolescent rite of passage. It’s a playlist passed along like a secret handshake, a CD in the car of a long midnight drive, and a heartbeat connecting one generation of kids struck dumb by doubt to the next.