From my cafe window at the mall, I noticed visibly excited Pakistani diaspora clicking selfies at the backdrop of a very large standee of ‘London Nahi Jaunga’, somewhere in Abu Dhabi.

A careful look revealed how fans posed themselves in a manner that a fragment of Pakistani superstars Humayan Saeed and Mehwish Hayat would appear in their photos. I could imagine from their hurried body language how instantly these pictures were to go up their social media.

The visible gaiety around their cinema synced well with the celebratory mood of Eid at the time. Movie theatres were playing houseful, and ‘London Nahi Jaunga’ was here to spread the cheer albeit for Pakistanis away from home.

As my cafe window inadvertently let me watch these sumptuous fan moments not so far away, I sipped my Ethiopian espresso, and drifted back to the memories of Cannes earlier this May inundated by those happy photos of the exuberant ‘Joyland’ cast and crew, the first film from Pakistan to win the Jury Prize in the segment of ‘Un Certain Regard’ along with the year’s Queer Palm Award at the 75th edition of Festival De Cannes.

‘Joyland’, directed by Saim Sadiq, had received unprecedented accolades at the Cannes Film Festival.

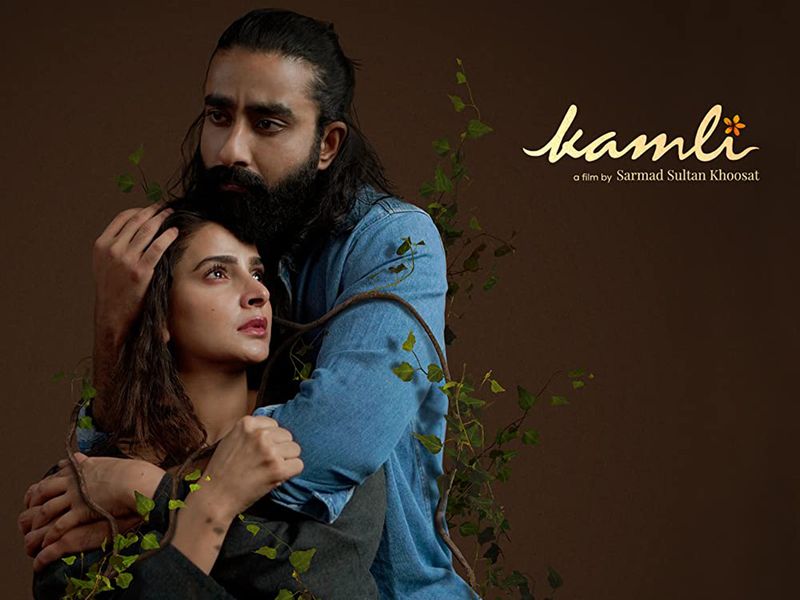

Then ‘Kamli’, directed by Sarmad Khoosat, one of the producers of ‘Joyland’, released in Pakistan. It played to its expectations, ensuring the balance of fine cinematic language and audience pull at their home turf. In the times of web, there isn’t much that’s limited. Hence one learnt more, saw more of the film, heard its melodious numbers.

And all this is evocative enough to sense that Pakistan’s cinema is in a happier state. But more than being in a happy state perhaps it is at an interesting, rather critical juncture as never before — a road full of possibilities.

Maybe its almost arriving there, creating an identity for itself in the centre of world cinema — Europe. Maybe it will come up shoulder-to-shoulder in its consistent burst of creativity with its other Asian fraternities; Taiwan, South Korea, Hong Kong, Iran and Japan, occasionally India, who had already built their legitimate space in the eyes of European movie goers.

It could be the other road too; of commercial cinema, which by no means is less enticing for Pakistan at the moment. Of late Humayun Saeed, Fawad Khan, Mehwish Hayat, Pakistan’s most sought after international actors, have been drawing attention of the South Asian diaspora worldwide and the West.

‘London Nahi Jaunga’, was in the 8th position in its first week’s run at the UK box office, topped by Fawad Khan’s and Hayat’s presence in ‘Ms Marvel’. A tiny video clip of Khan and Hayat in the series episode 5 has enamoured South Asians. However, for now, this discussion is more aligned to cinema that germinates a way of seeing, many times more than revenue, or is beyond nationalism transcending boundaries. Pakistani cinema is at that crossroad, albeit once again. Will it this time be able to sustain on that meditative, arduous path?

A little playback

Resurrected in mid 2000s, Pakistan’s cinema emerged into its phase of nuanced, fine storytelling, in a country embittered with restrictions.

Interestingly, incidents of censorship or limiting artistic freedom can happen even in the most democratic film environment. Satyajit Ray had to once face censorship when his film ‘Devi’ (1960) evoked controversy. Wrote Marie Seaton, Ray’s official biographer: “For a time, Devi embarrassed Union Government and resulted in a disinclination to send the film abroad”.

In Pakistan of mid-2000s, films like ‘Khuda Ke Liye’ by Shoaib Mansoor and ‘Ramchand Pakistani’ (winner of FIPRESCI award) by Mehreen Jabbar, pioneered a cinematic freedom and a visual language with social realism hitherto unseen. The growing realism was there to stay and some of it percolated to Pakistani drama series later.

Made with limited resources, these films led to a new cinema movement of Pakistan. They had more than one goals, of which bringing back the middle class moviegoers to the theatres was a primary, while simultaneously initiating a change in the way of seeing. Indeed a John Berger approach, who once said “When art is made new, we are made new with it. We have a sense of solidarity with our own time”.

Mansoor and Jabbar’s films resonated their individualism much like the oeuvre of Wong Kar-wai, Abbas Kiarostami or Asghar Sarhadi. But importantly, their cinematic vision also included a more palpable, but complex, impression of Pakistan, that helped the global and local viewer sense the country. I would bracket these film as deep social, cultural, political commentary perhaps more direct than their counterparts in Iran or Taiwan.

While ‘Khuda Ke Liye’ spoke of life changing events post 9/11, ‘Ramchand Pakistani’ was about the ‘peaceful life’ of a Dalit family living closer to the Indo-Pakistan border, and how an incident changed their lives almost for years.

Along with a host of other directors like Billal Lashari who made ‘Waar’ (‘The Strike’ in 2013), Meenu Gaur, who directed ‘Zinda Bhag’ (‘Run for Your Life’, 2013) a critically acclaimed film about illegal migration that became Pakistan’s entry for the Best Foreign language category at the Academy Awards that year, things were transforming for Pakistani cinema and how they were looked at outside Pakistan. Then came ‘Moor’ (2015) by Jami, a sensitive film about the woes of a station master at a small village of Balochistan called Khost, once again Pakistan’s entry to the Academy Awards.

In the interim though it was interrupted by political interventions, while the drama series industry saw an unbridled growth of passionate storytelling, many using lens of social realism. The South Asian audience do retain the dew fresh memories of soft and hard narrative series like ‘Zindegi Gulzar Hai’, ‘Pyare Afzal’, ‘Main Manto’, ‘Rehaai’, ‘Doraha’, ‘Neeyat’ and many more.

It is the legacy of this distinct cinema, cinema with atmospheric liquidity on which ‘Joyland’, or ‘Kamli’ stands. ‘Joyland’ in particular has the urgency to tell the complexities of society.

The recognition at Cannes has subverted the typical expectations from a cinema of Pakistan. It has brought the moment of glory for Pakistani cinema, something that seemed to be in ‘wait’.

With the ability to tell stories like ‘Mr and Mrs Shameem’ (on masculinity), ‘Ek Jhooti Love Story’ (on stratified society and idea of love in digital times) or ‘Parizaad’ (on gender norms) — Pakistan’s content has already had proven their storytelling mettle to South Asia. I don’t see ‘Joyland’ or ‘Kamli’ as one offs. ‘Parasite’ (South Korea, 2019), or ‘A Salesman’ (Iran, 2016) or a ‘Capernaum’ (Lebanon-France, 2018) is a possibility from Pakistan.

And if the final detracting argument is if these brought in money after releasing, they certainly do as their box office in the US reads but more than that they bring forth often unheard transformative stories, which is the biggest gain.

— Nilosree is an award winning filmmaker and author.