Ali Al Ameri, international horseman and owner of Rahal Ranch in Abu Dhabi, nestled in the dunes of the Al Wathba desert, dismisses the title of horse whisperer. He doesn’t want to be labelled as one. “There’s no whispering with horses,” he said, even mimicking whispering with a chuckle. “They call me a horseman, but I am a horse student. I learn from them. They have made me everything I am today,” Al Ameri explained, between sips of tea. “I don’t even like to call them animals,” he adds.

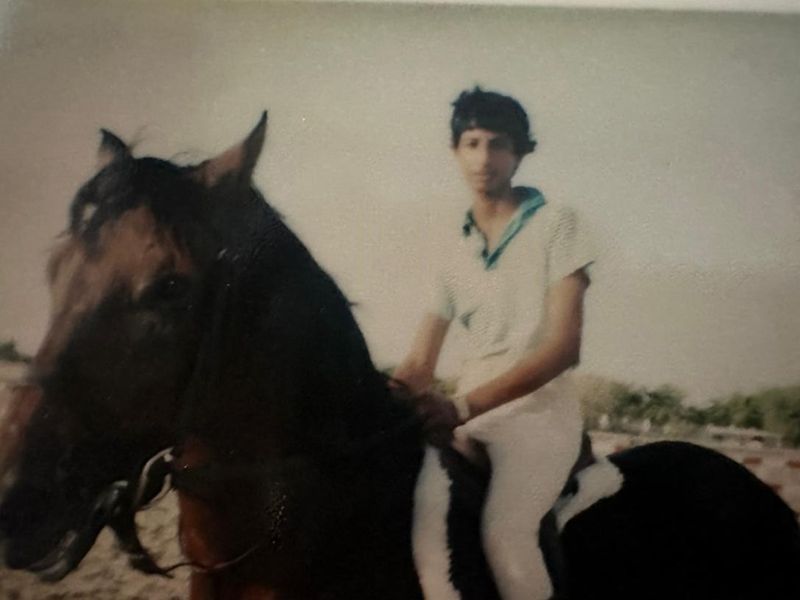

While eating dates, drinking tea and walking around with Adnan, a quiet, gentle brown horse around the sprawling ranch, Al Ameri shared the many stories from his life. While being a gifted horseman, he’s also a storyteller at heart. His whole life has been nothing less than an adventure, beginning from his childhood.

Without much of a preamble, he began, “I don’t know when I was born exactly. There’s no birth certificate and paper. I lost my parents when I was a kid, and my uncles looked after me in Al Ain,” he said. His uncles would argue over which year he was exactly born in, ranging from 1964 to 1967. “So now, whenever someone asks me when I was born, I say well, a long time ago,” he said with a wry smile.

Al Ameri cherishes his childhood. “I’ve grown up around animals in the desert. That’s where we lived. We used to play with camels and goats, cook food on fire in the desert, even if there wasn’t much wood. It was a beautiful life,” he recalled.

In 1974, he moved to Abu Dhabi with his family. Everything was almost a shock for him, especially the sight of the vast sea. “I kept saying, ‘There’s so much water here!’ There were boats and ships; and we would keep wondering how they managed to keep afloat. It was all so new to us,” he remembered. The sight of a car was equally frightening, he said, almost akin to a “monster”.

Escaping to the horses

This shift to Abu Dhabi entailed school; something he loathed. It was nothing less than torture for him, as he wished to remain outdoors. “I don’t like to see walls. I hated indoors. I wanted to be free, outside and see the blue sky. I would fight with the kids for the window seat,” said Al Ameri. He wasn’t a bad student, he emphasises; but his passion resided elsewhere. As the stables were close to his school, he would escape to be with the horses, whenever he could. Of course, he would inevitably get chased away, but he would go straight back to the horses, whenever he could. There was something empowering and powerful about horses, and yet, so gentle.

Pausing at this point in his story, he patted Adnan’s ears and nose gently. “They’re really the most forgiving species. They are so trusting, even when people are so cruel to them. They take it,” said Al Ameri.

Al Ameri showed his ‘magical’ touch with horses. He isn’t a whisperer; he was right. He just walked, and with a few gestures, the horse understood him. With a few words, he got Adnan to gallop around the sandy fields, while we watched. “Try running with him,” he told me with a wry laugh. “He won’t hurt you. He’s a gentle one,” said Al Ameri. Apprehensive at first, I ran a little, with Adnan right behind me. I touched the horse a little nervously, and even got a surprising nuzzle from him, before he trotted back to Al Ameri’s side.

The road to international fame

It’s this unusual talent of understanding the language of horses that brought Al Ameri international fame early in his life, in his twenties. Relating a story that sounds like something out of a novel, Al Ameri said, “I was working with horses in stables at that time. An Australian man named Heath Fields, had come to UAE, as he was bringing camels. He saw me working with the horses. I didn’t speak a word of English then,” he recalled. Field took keen interest in Al Ameri and wanted to take him to Australia. “He said that I had talent. I had no idea what he was talking about at first. Anyway, I went with him to Australia,” he said.

In Australia, Al Ameri was noticed for his unusual connect with the horses. As he explained, it normally takes four to five weeks to “break in” a horse, which means ensuring that they’re ready to be saddled and ride. However, it took Al Ameri just a day to get the horse ready to be saddled.

And so, in his words, “news began to spread”. This secret language of the horses took Al Ameri to different places around the world, including Europe and the United States. “I have been all around the world, for tournaments, racing, buying or fixing problematic horses,” he said. “I’ve just been horsing around since the 1980s,” he said, enjoying the wordplay. “In 2016, I had 16 wild horses from Montana, USA, and I got them ready for riding and brought them to Dubai,” he said with a little pride.

Understanding horses

When asked further about this connection with horses, Al Ameri preferred not to share much, but explained: “I convince them that I am their friend. They tell me what to do. I have to let them know that I won’t hurt them and that they can trust me. We can lie and act, but they can’t. I am two steps ahead as I can predict their next move… so they feel I am one of them,” he says. It has been Al Ameri’s passion for over four decades now, saving wild horses.

People don’t know how to deal with wild horses; they’re written off quickly, he says. “Some of them are lucky and go to riding schools, but others face a worse fate. There’s no one to help them. So here, we have horses that have come to us from different regions, wild and unsaddled. Some have never seen humans too. So, after I work with the horse, I give the trainers homework on how to look after the horse, so they don’t resort to their bad habits again.”

The story of Rahal

Al Ameri has a special relationship with each of the 56 horses on the Rahal ranch, but perhaps the closest to his heart is Rahal, after whom the ranch is named. “He was a bad horse. He was so hard to ride, everyone kept saying,” he reminisced. However, Al Ameri managed to “help” him in such a way, that the horse would only come to him. “He was special,” he remembered fondly. “He became my friend,” he said, as he showed us photos of him with the horse, his reins, and a few strands of hair from the mane that he preserved.

Speaking about the Rahal Ranch itself, “There was not much here, before the ranch, in 2006. I settled here in 2006. Now, we have a horse city here,” he said, saying that there are more than 300 stables in the vicinity.

The ranch life

“Who’s the boss here?” Al Ameri called out, to his staff member, Narayan Singh, who has been working on the ranch for the past 10 years.

“The horses, sir,” he answered. Al Ameri grinned at us and said, “The horses rule here.”

“How many people work here?” I asked. Al Ameri shrugged. “Too many.”

We then walked through the stables, where roosters were running free. Each horse’s name is printed on the door. The names are a colourful assortment, ranging from Chocolate, Tayyab to Shakira. As Al Ameri is full of anecdotes, he even had one about a horse that he named Dusty. “I named him Dusty, because the day he was born, there was a dust storm,” he said with a laugh. He doesn’t believe that horses should always remain in stables; they’re meant to run free. “Only when the weather is bad, or rainy, do they all stay inside. Otherwise, they’re outside,” he said.

As I listened, I watch one white horse lie on the ground and roll in the mud, just the way a dog does. “Oh he likes doing that,” said Al Ameri, who knows each horse like the back of his hand. While we walk around the stables, a small pony with a white star on the forehead peeks at us and runs away. That’s Biscuit, I’m told, by Aminah Asif, a 17-year-old horse trainer from Fujairah, who stays at the ranch. She has her own horse in the stable: Akeem, a rather demure brown male.

The horses aren’t the only inmates of the ranch; we were greeted by a field of hungry goats waiting for their food in a gated field. Somewhere, in the distance, two dogs, belonging to Al Ameri were running around and barking. “This is my home and family. This is how it is,” said Al Ameri, who stays at the ranch itself. He gave scant details of his personal life, he is married, and has three sons in their early 30s, both of whom live in the region and visit often.

There’s no particular routine on the ranch, Al Ameri emphasises. He wakes up in the morning at around 6am, has a cup of coffee, and then is with the horses. He rides them, watches over their grooming and inspects their shoes, to see if they have gotten hurt in any way. People come for horse riding lessons, and then the ranch closes by around 11 am. “It gets hot by then. After lunch, we’re back by 3pm. By 7pm in the evening, friends come over and we have a barbecue,” he said. If the horses are unwell, he and the staff stay up with them for the whole night, tending to them with drips. There’s a vet nearby.

During the summer months, the horses are kept comfortable in the air-conditioned stables while Al Ameri takes some time out and heads to be by himself, enjoying his own solo adventures and hikes. He doesn’t rely on technology as he says, in fact, he doesn’t even have an email address. “I’m old school. I don’t need it,” he said contentedly.

Note: This article was first published on November 16, 2023.