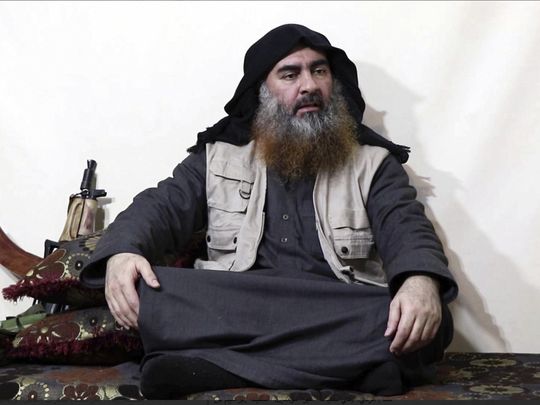

Obituaries, announcements of deaths accompanied by short biographies, make for sad reading. Some obituaries, however, we read with pleasure. One such is the obituary of Abu Bakr Al Baghdadi, who was hunted down and killed last Saturday in a night-time raid by American Special Operations commandos based in Syria.

Al Baghdadi lived to be 48 years old, which is — given the man’s calling — was 48 years longer than he deserved. His passing brings to mind the line spoken by Malcolm, one of the king’s sons in Shakespeare’s play, Macbeth, heralding the execution for treason of the traitorous Lord Cawdor, “Nothing in his life became him like leaving it”.

Who among us, whose job is to report or interpret the news, would forget that day in Mosul, Iraq, on July 29, 2014, when the Iraqi-born Al Baghdadi mounted a mosque pulpit there and made public the formation of a worldwide caliphate, known as Daesh?

And who among us, additionally, would forget that audio-taped message released days later of Al Baghdadi declaring, bizarrely, that after uniting all Muslims, soldiers of the caliphate would then “march” on Rome and “liberate” Spain.

Al Baghdadi lived to be 48 years old, which is — given the man’s calling — was 48 years longer than he deserved. His passing brings to mind the line spoken by Malcolm, one of the king’s sons in Shakespeare’s play, Macbeth, heralding the execution for treason of the traitorous Lord Cawdor, “Nothing in his life became him like leaving it”

In the man’s anachronistic Arabic, Rome was generally understood to mean the West and Spain was Al Andalus, the expanse of territory in Medieval times that Muslims governed as a cultural and political domain in the Iberian Peninsula between 711 and 1492.

Ludicrous and outlandish his claims may have been, Al Baghdadi went on to build a global terrorist network that, at its peak, drew into its orbit tens of thousands of recruits from 100 countries, and controlled swaths of urban, rural and desert territory the size of Britain — a sphere of influence watched over by deluded, but dedicated caliphniks who saw themselves as the vanguard of the “jihadist” movement — and they, like their leader, were cruel, barbarous and nihilistic.

They were quick to project a penchant for wanton violence and contempt for human life. And they beheaded innocents, enslaved minorities, destroyed cultural treasures, raped hostages and tortured captives. In short, they embodied evil.

The horror they wrought was beyond all rational understanding.

Yet, with all that said, the phenomenon that Al Baghdadi and his terrorist network epitomised was not unique to our part of the world, not by a long stretch.

Consider, for example, Thomas Muntzer, the German preacher and radical theologian who led a scorched earth peasant uprising in 1525 that terrorised Europe; and more recently in history, Adolf Hitler, the failed small-time, unemployed graphic artist and agitator, whose Nazi hordes and venomous ideology were responsible for much destruction, suffering and death, so much that Ian Kershaw, the renowned English critic, whose work has chiefly focused on the political culture of 20th century Germany, said of the mustachioed fuhrer, “Never in history has such ruination — physical and moral — been associated with the name of one man”.

Then there are, among countless others around the world, the likes of Stalin, Pol Pot, Ivan the Terrible (the murderous first tsar of Russia) and, lest we forget, King Leopold of Belgium, whose soldiers in the Congo, virtually gratuitously, killed 10 million Congolese.

Well, let’s say it then, evil is not the monopoly of any one people, any one region, any one epoch, any one faith. It is, simply put, part of the human condition.

Different cultures throughout history have struggled to understand, perchance to master, this inscrutable force in their lives and virtually all of them ended up concluding, after climbing the same mountain from different sides, that evil is there because, well, it is there, posited at a point in our objective reality where our human contradictions intersect. Period.

In Islam, the concept of evil, which resembles that in its two sister faiths, Christianity and Judaism, holds that it is visited upon us as punishment for our sins or presented to us as a test of our powers of endurance. No more. Another period.

For Al Baghdadi, whose delusional whimsies about conquering Rome and liberating Spain have cost countless people unspeakable suffering, the party he threw back in 2014 is now over. But his nihilistic legacy will continue to haunt our modern history long after he becomes forgotten dust. Damn the man.

Fawaz Turki is a writer and lecturer who lives in Washington and the author of several books, including the Disinherited: Journal of a Palestinian Exile.