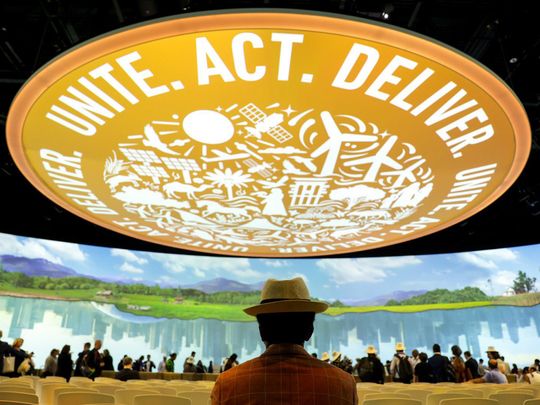

The ongoing UN Climate Conference COP28 in the UAE is witnessing a record number of delegates, a testament to the escalating global concern and engagement on climate issues.

However, this surge in attendance, particularly the involvement of a diverse array of non-state actors while there is a climate treaty in place since 2015, necessitates a critical examination of the efficacy of these annual summits.

Historically, climate negotiations were predominantly the realm of nation-states. The recent COPs, including the staggering 97,000 delegates at COP28, reveal a dramatic shift. Of these, only 24,488 represent the nation-states — the primary parties to the convention.

The rest include a broad spectrum of non-state actors: environmental NGOs, activist groups, intergovernmental organisations, city networks, businesses, indigenous communities, and others. This trend, spurred post-Copenhagen Conference in 2009, signifies a more dispersed, polycentric approach to climate governance.

While the inclusion of non-state actors democratises the negotiation process, it also introduces complexities. These actors bring divergent, often conflicting agendas. Some businesses push eco-friendly policies; others indulge in greenwashing or advocate deregulation.

NGOs range from those seeking insider status to those demanding radical systemic changes. The rise of the climate justice movement further diversifies this landscape with its energetic activism and global protests.

Ability to mobilise funds

Though the states can hold some closed-door meetings, however the myriad of voices at the climate summits, while enriching the dialogue, complicates the negotiation process.

The state’s unique position in this arena is defined by its sovereign authority, legal power, and enforcement capacity. Unlike non-state actors, states can enact laws and policies that address climate change challenges effectively and comprehensively.

This legislative power is complemented by the state’s ability to enforce these laws through various mechanisms, including regulatory agencies, environmental protection bodies, and judicial systems. Moreover, states can integrate climate concerns into broader policy areas such as urban planning, energy policy, transportation, and industrial regulation.

States possess the financial resources and institutional infrastructure necessary for large-scale initiatives on climate change mitigation and adaptation. Their ability to mobilise funds, enforce regulations, and incentivise sustainable practices is unparalleled.

State ratification and implementation

Governments, with their ability to mobilise significant financial resources, are uniquely positioned to fund large-scale climate projects and research, which are often beyond the reach of private entities or non-governmental organisations.

The battle against climate change is also inherently global, transcending national borders and necessitating international collaboration. Thus, international climate agreements, pivotal in the global response to climate change, rely on state ratification and implementation.

When a state ratifies an international climate treaty, it signifies a commitment to adhere to the treaty’s provisions and integrate them into national law. This process is vital because it translates global objectives into national action, making the global fight against climate change tangible and actionable at the local level.

No doubt, the battle against climate change requires a multifaceted approach. While non-state actors contribute innovation, grass roots mobilisation, and pilot new ideas, the state is the conductor of this symphony. It sets the tempo and ensures a harmonised collective effort toward common goals.

In the urgency of the climate crisis, the involvement of an excessive number of non-state actors at negotiation tables is therefore sometimes counterproductive. It makes climate governance more cumbersome and detracts from the efficiency and focus required for immediate and effective decision-making.

The adage “too many cooks spoil the broth” is apt in this context. The sheer number of participants and the diversity of their agendas dilute the focus and efficacy of climate governance, leading to delayed suboptimal outcomes.

Central role of nation-states

To effectively address the climate crisis, particularly in achieving global net-zero emissions and securing necessary climate financing, it’s crucial to reaffirm and prioritise the primary role of nation-states in negotiations. For cohesive and decisive action, as well as the formation of binding international climate agreements, the main responsibility must rest with the nation-states.

They possess the legal authority, financial resources, enforcement capabilities, and diplomatic influence crucial for impactful global climate action. Additionally, they bear the responsibility to safeguard the rights and interests of their historically, socially, and economically disadvantaged citizens during climate negotiations.

Nation-states are pivotal in enacting laws, mobilising resources, and establishing international treaties, all of which are essential for a coordinated and effective global response to climate change.

They have historically signed and administered several international treaties, such as the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, the Antarctic Treaty, the Outer Space Treaty, the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, and the Convention on Biological Diversity, to protect global commons.

Given this track record, why shouldn’t nation-states be entrusted with the responsibility to protect the planet from climate change?

While the involvement of various actors in climate negotiations reflects global concern and commitment to addressing climate change, it is vital to recognise and reinforce the central role of nation-states.