The coronavirus pandemic has stress-tested the world. Beyond challenging human fortitude, national health services and international rivalries, it has forced a series of moral choices. Many have provoked impassioned disagreement — over whether governments can force businesses and schools to close, over sacrifices for the sake of the elderly and, most bitterly and surprisingly, over whether being asked to wear a simple face mask infringes individual liberty.

The toughest moral test lies ahead. The biomedical industry and research facilities around the world are progressing toward creating a vaccine that would offer the best chance to end the pandemic and return life to normal. But the moral dilemmas provoked by the development and distribution of a vaccine will drive ever deeper debates.

The issues strike at profound divisions between schools of ethics. The newly published ‘Ethics and Pandemics,’ an anthology edited by philosophy professor Meredith Schwartz of Ryerson University in Toronto, presents contrasting views of academics, doctors and commentators along with a series of impossibly difficult case studies. The scientific, economic and political choices involve moral issues that have divided ethicists for centuries:

How to develop the vaccine?

The US government says the COVID-19 vaccine will be developed “at warp speed.” But vaccines take years to develop, for good reasons, and none of the benefits can be realised if they are released before they are safe. A failed COVID-19 vaccine could even compromise confidence in other vaccinations, threatening a return of measles, polio and other plagues.

Testing shortcuts are available but fraught. The first rule of deciding when they’re justified, explains Arthur Caplan, the head of bioethics at the NYU Langone hospital system in New York, is that risks can be balanced against the prospect of better data. Thus, skipping animal testing may pass muster since the data from testing humans is better.

That leads to the issue that divides teams at Moderna Inc. in Boston and at Oxford University in England who are working on the two most promising attempts to find a vaccine. How much risk of harming humans can they justifiably take? The best way to accelerate the process could fall afoul of the long-established obligations of medical ethics, from the Hippocratic oath to “do no harm.”

That pledge is as old as ancient Greece, it aligns with the powerful school of rights-based philosophy identified with the 18th-century German philosopher Immanuel Kant, which holds that people should never treat humanity as a means to an end. Whatever the ultimate positive consequences, Kantians argue, there is no right to harm anyone. Virtuous ends do not justify unethical means.

Moderna opted against human challenge trials, and instead started a conventional trial with 30,000 test subjects in July. Volunteers are given either the vaccine or a placebo, and then go about their daily lives as the pandemic rages. Moderna hopes to have scientifically reliable results by the end of the year. Tal Zaks, Moderna’s chief medical officer, said he expects this approach to reveal how the vaccine behaves with different groups of people and in different regions. By testing in the real world, he said, results can be superior to the outcome of challenge tests, which are held in laboratory conditions.

But the conventional approach is slower, and leaves much to chance. Oxford’s attempt to hold such a study in London and Oxford earlier this year came just as the epidemic was beginning to decline in the UK, making it hard to draw firm conclusions. A rival research team at Imperial College, London, has the same problem and is looking to hold a trial in another country.

Further, doctors are morally obliged to tell volunteers how to avoid getting infected. They cannot tell them to go maskless, or to seek out crowded spaces, even though from a narrowly scientific point of view this would improve their test results. It’s also impossible to monitor so many volunteers closely enough to determine if they are reporting their experiences inaccurately and skewing the results.

How can the vaccine reach a critical mass without compulsion? An employer might demand vaccination as a condition of reporting for work. A university might impose the same requirement on faculty and students.

Rutgers University bioethicist Nir Eyal says that coronavirus challenge testing in the U.S could simultaneously “maximise utility and respect rights.” Researchers would use only “informed, willing, low-risk volunteers” from a population that is already in high-risk areas, he said.

Volunteers are abundant. An advocacy group called 1 Day Sooner has found 32,000 volunteers in 140 countries, all between the ages of 20 and 30, (old enough to consent but much less exposed to serious harm from COVID-19 than their elders) with no relevant underlying medical conditions. Strongly believing in effective altruism, Josh Morrison, who heads 1 Day Sooner, voluntarily donated one of his kidneys to a stranger, as did others helping with the campaign.

But Kantian objections are serious. Michael Rosenblatt, a Harvard Medical School professor and former chief medical officer of Merck Inc., objects that human challenge studies should only be contemplated when some lifesaving treatment, such as an antiviral medicine, is available for a candidate who gets sick. There is no such cure for COVID-19.

Then there is the problem of the unknown. Vaccines must pass muster with libertarians, descended from figures such as the enlightenment philosopher John Locke and the founding fathers of the US, who build morality around individual freedom. To counter libertarian objections, researchers must obtain “informed consent.”

Rosenblatt argues that when it comes to COVID-19, “It’s pretty hard to have informed consent when we barely know anything about this yet.” There are fears that the virus can cause lasting damage even in twentysomethings, for example, but little clear evidence. Can volunteers really consent to expose themselves to such poorly understood risks?

Finally, there is the appalling possibility of a volunteer dying. In 1999, this happened to Jesse Gelsinger, a healthy 18-year-old with a rare metabolic genetic disorder who volunteered for a conventional safety trial (not a challenge trial) of a virus-based gene therapy. His death was both a personal tragedy and a scientific disaster that “set the field of gene therapy back by at least two decades,” Rosenblatt said. “That hiatus deprived a generation of patients with genetic disorders of treatments.”

Morrison, of 1 Day Sooner, defends the right to volunteer for testing. Estimates at present are that the risk of death from COVID-19 for people in their 20s with no pre-existing conditions is under one in 10,000 — less than the risk of dying in childbirth while soldiers (whether volunteer or conscripted) face a far higher chance of dying on the battlefield.

How to pay for the vaccine?

“A vaccine is meaningless if people are unable to afford it,” said John Young, the chief management officer of Pfizer Inc. Nobody asserts that drug companies should be able to charge whatever the market can bear for a COVID-19 vaccine.

But private companies like Pfizer have a responsibility to shareholders. Moreover, anyone who develops a successful coronavirus vaccine will have performed an immense service to humanity and will deserve to be rewarded. And so Pfizer defends its right to make a profit.

Pfizer has a $2 billion deal with the US government to supply as many as 600 million doses of the vaccine it is developing. Many of its competitors are in collaborations with public universities, or receive state funding. That raises an intensely ideological issue: Should a private company be free to set prices for a public good developed with government aid?

“We have to make a profit out of the first product,” Moderna chief executive Stephane Bancel told Yahoo Finance. “We have invested $2 billion of our shareholder capital since we started the company. We need to get a return.” But Moderna has also received some $955 million in government funding to finance its big test. According to the Financial Times, Moderna is planning to price its vaccine at $25-$30 per dose, significantly above the $19.50 at which Pfizer is selling each of 100 million doses to the US.

Meanwhile, AstraZeneca PLC says it will sell the vaccine it is developing with Oxford to European governments at no profit, while Johnson & Johnson says it will sell its vaccine at a “not-for-profit price” for emergency use.

The issue is already very political. Five pharma industry leaders have had to testify on their pricing plans before a committee of the US House of Representatives, and Democratic-sponsored bills are in Congress to stop price gouging. They have some Republican support.

Representative Lloyd Doggett, a Texas Democrat who is sponsoring one such bill, told Politico that “a drug company’s claim that it’s providing a vaccine at cost should be viewed with the same scepticism as that by a used car salesperson.”

Once governments have bought the vaccine, should they require patients to pay for their own shots? Most people with money would happily pay much more than $30 to free themselves from the coronavirus. But in the many developed countries with nationalised health systems, the question doesn’t arise: taxpayers pay, and the vaccine is free for patients.

The US, however, has a political issue on its hands. Senator Patty Murray, a Washington Democrat, now backs a bill to ensure that every American has a right to a free vaccine. Meanwhile, the deal with Pfizer will result in free immunisation. Having established the principle of taxpayer-paid vaccines, it could be hard to retreat.

These are issues decided within countries. When it comes to international cooperation, poorer countries complain about “vaccine nationalism.” In the UK, Prime Minister Boris Johnson pulled out of the EU’s so-called Inclusive Vaccines Alliance in a move attacked for playing to his Brexit-friendly political base.

Wealthy countries have little incentive to collaborate with poor ones. Costa Rica led an effort with the World Health Organisation to set up a new “COVID-19 Technology Access Pool” that would share research and then coordinate production — and also share the vaccine once it was ready.

But the list of countries that responded is telling. The US, China, Canada and Japan are all absent, while the only European countries to sign up have been Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Norway. A group of much smaller developing nations has been left to build a collaboration — even though the virus knows no boundaries, and it is in all countries’ interest to stamp it out everywhere.

Meanwhile, rich countries are prospectively buying up vaccines before they have even been cleared for use. The US-Pfizer vaccine deal, and a similar deal with Glaxo PLC and Sanofi AG, uses American buying power to avoid excessive prices. Britain has done four separate deals with providers for 250 million doses.

What about the poorer countries who may have to pay more for the vaccine? For now, attempts at “vaccine justice” have been left to philanthropies such as the Gates Foundation’s Vaccine Network.

How to ration the coronavirus vaccine?

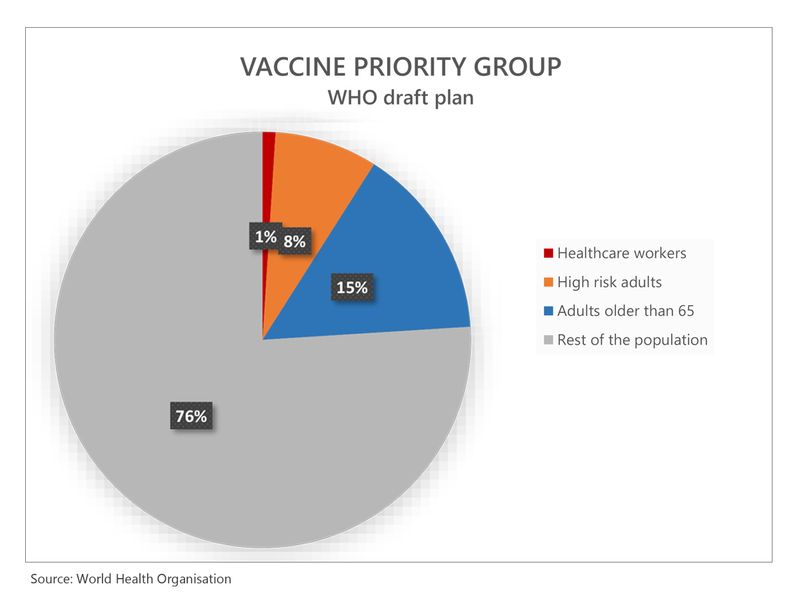

The pharmaceutical industry cannot produce enough vaccine for the entire global population of almost 8 billion all at once. Therefore, rationing is inevitable. Some people will have to wait. Who gets to make these decisions, and by what criteria?

Within the US, various medical bodies and government agencies claim authority to draw up the guidelines. No one seems empowered to adjudicate.

“The principle is to protect those most likely to be harmed,” said Caplan of NYU Langone. That leads to one point of clarity: Medical workers go first. They’re obviously at risk, and have a duty to put themselves in harm’s way.

But after this, following his criterion leads to prioritising some of the least privileged in society “” not because they are underprivileged and deserve help, but because they are most at risk.

Statistically, prisoners follow doctors and nurses on the list of people most likely to be harmed. As prisons are COVID-19 incubators, Caplan suggests that vaccinating inmates would limit the disease’s spread.

Within the US, Native-American communities are grievously affected, and therefore have a case for priority. The same is true of some other ethnic minorities, largely because they tend to live in crowded communities, and because higher rates of poverty make them more likely to suffer the underlying conditions that make COVID-19 more deadly.

People are also more at risk if they cannot work from home. Anthony Skelton, a philosophy professor at the University of Western Ontario, makes a case for sending those in work-at-home professions to the back of the line.” To the extent that racial minorities might live and/or work in conditions that make them less able to avoid coming into contact with infected individuals, the case for giving them priority over people who can work from their home office seems strong,” Skelton said.

read more

- Newsmakers: For Sarah Gilbert and Stephane Bancel, failure isn’t an option in the search for COVID-19 vaccine

- COVID-19 vaccine: Here’s what science tells us

- COVID-19 vaccine: Scared that coronavirus immunity won’t last? Don’t be

- What to expect when a coronavirus vaccine arrives

- Spike in COVID-19 cases globally no reason to panic

All of these proposals spring from prioritising people according to risk, but might in practice look like the kind of redistributionist social-justice crusading that provokes controversy, particularly in the US.

Rationing could also be affected by where the vaccine was tested. In the case of AIDS, experimental treatments were assessed in Africa, where testing was cheaper, but the treatments then went to developed countries. Severely affected African countries had to pay prohibitive prices as the disease took hold.

Africa could become a COVID-19 test site if regulators do not permit human challenge tests elsewhere. If large-scale testing does happen there, justice will demand that early supplies of the vaccine are made available to Africans, even at the expense of people in the researchers’ home country.

Should COVID-19 vaccine be made compulsory?

Vaccinations work best when everyone receives them, since germs that can’t infect people tend to wither away.

But all vaccines come with risks. That creates a “free-rider” problem. The best option from a self-interested point of view is that everybody else has the shot (eliminating your personal risk of catching COVID-19) — but that you don’t (avoiding any personal risk of side-effects). Taxes have the same problem. Taxes are compulsory. Does that mean vaccination should be compulsory, too?

The public-health case for compulsion is strong. But libertarians have a problem with forcing a potentially harmful vaccine on someone without the “informed consent” that’s hard to procure in societies sceptical of experts and low on social trust.

How can the vaccine reach a critical mass without compulsion? Caplan suggests leaving compulsion to private entities. An employer might demand vaccination as a condition of reporting for work. A university might impose the same requirement on faculty and students. A vaccine might be dangled as a golden ticket to return to theatres, cinemas, night clubs or sports events. Governments or foundations could even pay people to receive a shot.

By this thinking, those who assert their right not to be vaccinated would be free to work from home and home-school. They would be voluntarily narrowing their own freedom of movement and assembly.

Yet societies would pay a price. The virus has divided humans in countless ways already. If many citizens opt to stay unvaccinated, the virus and the messy ethics of compelling vaccination will have helped to create another permanent division.

— Bloomberg

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. He is the author of “The Fearful Rise of Markets” and other books. Twitter: @johnauthers