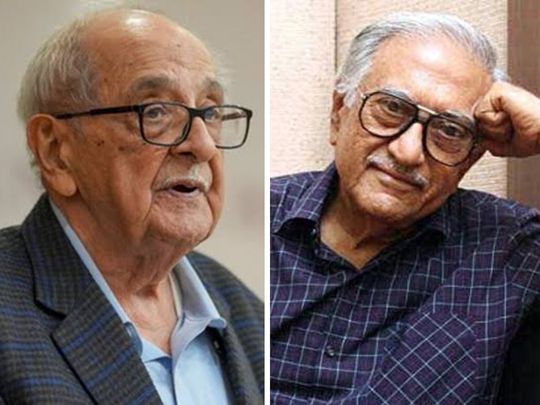

India lost two giants when Fali Nariman, the fiercest sentinel of India’s Constitution, passed away, and Ameen Sayani, quite literally the soundtrack of lives before radio had jockeys and huge market compartmentalism, died. Both Nariman and Sayani lived to a ripe old age and, in many ways, were the last of the men who had created and shaped a kinder, gentler, more egalitarian India.

From my babyhood, before I even learnt to speak and understand language, Sayani’s familiar voice on the radio, gentle with literally a smile when he introduced songs, lulled me into comfort. The radio played all day in the house, sometimes turned up when his signature Bianca Geetmala came on the radio of my young aunt or my father, whose love for music I inherited, or for the news by my grandfather.

Sayani’s baritone voice and his beautiful enunciation captured the heart of India in a time when film music was lyrical, meaningful, and giants like Kishore Kumar, Mohammed Rafi, Asha Bhonsle, and Lata Mangeshkar sang and ruled the charts. The songs were classics in the making, not instant so-called “viral” hits.

Some of the songs introduced in Sayani’s soothing voice provided the elusive “sukoon” closest translation (peace) that one sought. Obviously, unlike today, when there is objection to name of a colour “besharam rang” if you remember the Shah Rukh Khan starrer Pathan — ridiculous controversy over a song didn’t happen.

When Nariman and Sayani started, India was still a relatively young, idealistic country proud of our democratic values, trying hard to understand other fellow citizens. Hearing the Indian national anthem “Jana Gana man” written by Rabindranath Tagore sung beautifully and played on the radio still made us tear up. I still remember my grandmother, my dadi, crying every time Latajee’s came on the radio and sang “Allah Tero Naam,” her favourite prayer.

Markers of a gentler, more embracing India

Nearly every Indian had a transistor set, and if they didn’t, they would sit in the village paan shop clustered around a huge tree or the “chai ki dukaan” (tea shop) and listen to the radio. Radio truly ruled, unlike today, when various media alongside social media compete with our tiny attention spans.

We scroll, but we don’t quite internalise what we constantly swipe. As radio ruled, so did Sayani, but he was a gentle ruler, making us think and get in touch with our best sides as he mellifluously curated the top of the pops, the chart list India listened to.

I met Nariman after I became a reporter in the Delhi High Court, where I was summoned in a case to reveal my source for an investigative story. I used to work for The Statesman then, and the redoubtable late C R Irani was the Editor. He appeared with me to show support for my stand that I was willing to go to jail if the Court ordered.

Nariman suddenly appeared and sat in the Court. The judge thankfully ruled that I didn’t have to reveal my source for the story, and he wouldn’t send me to jail. Suddenly, Nariman loomed up and patted me on the back, saying, “you are a brave young lady and deserve a chocolate bar. Never lose your journalistic values. All of us, you, the free press, we the lawyers, should only worship lady Justice and our Constitution. Don’t ever back down. And, if you get in trouble again, I will fight for you.”

Pleasant, unifying symbols

Such reassuring words for a young reporter from such a distinguished counsel. Before parting, Nariman added with a twinkle in his eye, “I know CR (Irani) wouldn’t be paying you much so I will appear for you pro bono.” That blanket assurance has gone now.

Nariman was the doyenne of the legal profession when it came to Constitutional law. But, he wore his laurels lightly. Nariman publicly admitted that representing Union Carbide and arguing for them in the infamous Bhopal gas tragedy was a mistake.

A member of the Rajya Saba, the house of elders in the Indian Parliament, Nariman didn’t ever take positions on partisan lines. In one of our meetings, he said he was sad to see lawyers and the bar get divided along political lines, saying that the rule of law and the Constitution should be the only guiding light of lawyers. Again, like Sayani and Indians of that generation, unity and not fault lines concerned Nariman.

Even at the age of 95, when most people would have given up public life, Nariman wrote a letter to senior lawyer Prashant Bhushan congratulating him on the outcome of the controversial electoral bond case which was struck down by the Supreme Court of India as “illegal”.

We will never hear Sayani again, and we will not witness Nariman’s passionate defence of our Constitution, and we are the poorer for it. RIP.