On a summer afternoon of 1770s Antoine Polier, a Lausanne born engineer, businessman, soldier, scholar, spy all rolled into one, sat down to write a letter to a Lucknawi artist called Mihr Chand. In a rather sardonic tone he instructed Mihr to finish the commissioned art at hand and swiftly move on to the next lot.

It could be anything that Mihr would paint next, from vivid portraits of tawaiefs to whose mehfils Polier would frequent, or foliage, flowers, vignettes of everyday life, portraits of sheikhs, birds in nature, basically life and times in 18th century Indian subcontinent.

However commissioning art for private consumption wouldn’t remain an exception. The same decade will witness some riveting happenings in patronising and producing art.

“From Olympian detachment above the bawdiness of his contemporaries was the rotund figure of the Chief Justice of the new Supreme Court Sir Elijah Impey”, writes historian, and art historian William Dalrymple as he introduces Elijah Impey in the anthology “Forgotten Masters, Indian Painting for the East India Company”.

Even though Impey’s legal career can’t be attributed as ‘rotund’ with the controversial execution of Maharaja Nanda Kumar, a scar on Impey’s judicial career yet Dalrymple’s words somewhat fit in to the juror’s contribution to the art scene of late 18th century. Impey and his wife Mary settled in Kolkata in 1773. Going ahead, they would play a major role in fostering the artist and art circle of the colonised subcontinent.

Between Impeys, Polier and their friend one Claude Martin, they hold the credit of promoting perhaps the first round of the brilliant artworks, sparkling in their originality termed as ‘Company Painting’ and their creators ‘Company Painters’.

Polier and Martin passionately replicated lives of the Mughal nobility and like the Mughals they also became connoisseurs of art. Martin’s case was of extremes. About 17000 drawing sheets, mostly imported from England, finest produce of Whatman, Britain most famous paper making company were a part of inventoried items discovered on his death in 1800!

Though there are records of earlier art commissions by Jesuit missionaries who visited the court of emperor Akbar’s and by travellers like Nicholao Manucci, yet these commissioning weren’t catalytic to the growth of new style ‘Company Painting’ or in bolstering the demand for these paintings in Europe.

The Rise of a New Aesthete: Company Paintings

It’s not easy to zero in which East India Company officials commissioned artwork had set the trend of this hybrid style yet Claude Martin can be attributed as the trendsetter to have started commissioning a range of art to the Indian origin painters, that were formerly trained in Mughal artistic style, some of them even belonging to imperial families of ateliers.

What are the reason for the rise of these painters in cities like Murshidabad, Lucknow, Calcutta, Delhi, Patna, Tanjore and what factored a successful patronage right from Martin to Hastings to Francis Buchanan Hamilton? Would these local artists not be happy assisting the British water colourists and painters or merely drawing an occasional portrait of a Nawab or a white Mughal?

Like all empires that boast of their sun to never set (symbolic) and invariably crumble someday, Mughal Empire too had a rapid downfall. By the time Mohammad Shah popularly known as Rangeela ascended the throne in Delhi, the empire had started falling apart.

Multiple causes have been cited as the reason for the decline of world’s one of the largest and prosperous empires, of which loss of revenues, prolong wars in various regions, lack of confidence for the central governance, battles over succession, maniacal luxury, exploitative relationship with the vast peasantry, and the strengthening of East India Company were foremost.

With East India Company flexing their muscles in controlling India, English men in large numbers arrived from England.

Some of the expats were trained artists. They took to drawing India and its sights and sounds, smitten by the grandeur of the ‘unknown’. The list is long with the likes of Charles D’Oyly, S C Belnos, William Prinsep, Thomas and William Daniell, Palmer, Solvyns and others.

Daniells were a uncle nephew team, who became famous touted as the finest of British landscape artists with a sizeable volume of art they produced in India while others like D’Oyly and Prinsep got involved in art as a hobby while being employed with East India Company.

Alongside these trained artists, there were other English men who were simply curious about the unusual country, noticing the vignettes of life here. They started hiring Indian artists. The artworks produced adapted European style, colour palette mixed with the existing stylistics of various miniature schools resulting in hybrid aesthetics distinct from their influences.

Thus Company Painting became a generic, umbrella term for innovative artwork brought to life by private patronage and were catalytic to forging new relationships with Indian artists some of them being finest painters of their times and with a wide commercial market that spanned beyond England.

The Path That Emerged

The art that these Indian artists produced were their responses to the world. They were marked by distinct use of colours, brilliant details, stroke pattern, and sparkling highlights by way of light and shadow, resulting in a cinematic effect. It is an irony that when Company Painting disappeared from public recall they would be displaced by the advent of photography.

From Claude Martin to Elijah Impey to Warren Hastings to James Skinner, William Fraser the collective art commissions were diverse; a world of unseen flora and fauna, glimpses of everyday life, architecture, shrines, modes of transports, festivals and celebrations and what not.

Beyond their artistic excellence Company Painting also centred around the complex interest of the colonisers, the ruthless aggression of East India Company, a militaristic trading entity whose representatives used art to tacitly engage in diplomacy, pump up social mobility and most importantly to gain knowledge about territories which they would transform into their colonies.

Sita Ram was a Bengali painter who accompanied Governor-general Warren Hastings on a trans country trip by boat in circa 1814-15 travelling from Calcutta to up north. Hastings was the commander in chief and a pan subcontinent journey was not undertaken for a rejuvenating cruise.

Hastings needed to know the territories better, forge diplomatic engagement with Indian rulers and inspect the on ground realities. Sita Ram recorded the entire journey like a visual commentary rooted in the current political atmosphere of the times.

Of the 239 paintings that emerged in the art circuit as recently as 1975, one noticed a stylistic combination of English landscape painting and Indian aesthetics a lingering reflection of the training that Sita Ram had in Murshidabad, Bengal.

During the course of the travels that lasted for months Hastings and Sita Ram built a relation that was more than a patron and an artist. Hasting’s diary reveals minute details of the trip, which had an entourage of not less than 10,000. He mentions Sita Ram often accompanying his wife in sight seeing, while he conducted meetings.

This to me is an exceptional case of patronage expanded to quasi friendship. The artwork created was from Hastings point of view astute by the artistic swipe of Sita Ram’s imaginative mind. Surprisingly such an important body of work produced in colonial times, resurfaced as recent as in 1974.

On other instances albums created were results of the patron’s curiosity about everything in their new life, read living in India and panache to record private initiatives — the case in point is ‘Impey Album.’

Elijah Impey and his wife Mary decided to have a private menagerie in Kolkata of 1770s. At some point while nurturing their peculiar hobby the couple hired a group of three Indian artists, native to Patna to draw the animals of their zoo.

While the main task of the artists namely Bhawani Das, Ram Das and Sheikh Zain-ud-Din were to paint subjects of natural history, interestingly there were paintings that also depicted private lives of the Impeys.

Drawn between 1777 and 1783, the 326 paintings have been described as the finest of Company Paintings often referred together as ‘Impey Album’. The three artists proved their mantle with detailed studies of plants, mammals, fish, reptiles and even insects all bearing reaffirmation of their training in Mughal artistic technique laced with meticulous details.

Mary Impey closely monitored Zain-ud-Din works which are now much coveted in the private and public art collections. These creations reflect his successful repurposing laden with Indian sensibility and European scientific precision.

What is startling is the vitality of these paintings that ushers the memories of specialists in Akbar and Jahangir’s court namely Miskin, and Mansur whose natural history drawings had gained acclaim in their active years within the network of imperial patronage. Pertinently Mansur was Jahangir’s best flower and animal painter and Miskin worked in Akbar’s court.

If Zain-ud-Din and his friends Ram and Bhawani Das’s oeuvre had raised immense curiosity and attention in recent years, there were others who hadn’t left any clue of who they were and how did their fabulous artistic career began and prosper. Few words put together in artist’s signature were the only window to their personality.

Such was the case of 19th century’s one of the greatest of Indian artist; Sheikh Muhammad Amir of Karaya identified himself as a ‘musavir’ or a professional sketch artist.

His successful career catering to the British market had remained in anonymity as recent as 2000s. Records tell he was resident of Ballygunj in Kolkata active in1830s in this neighbourhood predominantly inhabited by the locals and adopted a unique style of painting to cater to the demands of the growing art market.

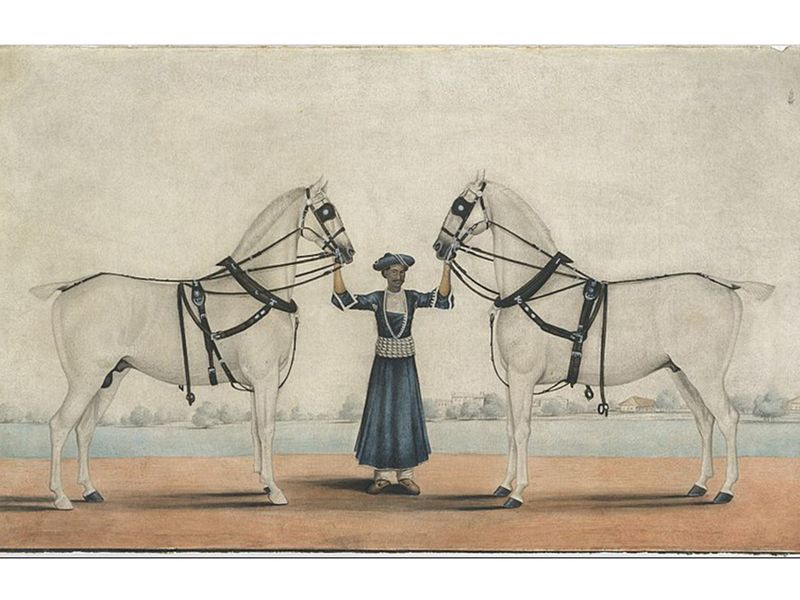

Unlike Sita Ram or the trio Impey artists, Amir’s work oscillated and overlapped between the brown and the white world. Some of his prominent creations feature the labour force from local English households, like a sahish (keeper of a horse) handling horses or a manservant escorting a British baby girl on a horseride.

While the paintings apparently enumerated a colonial life, Amir successfully included the fringe elements read the Indian working class in his artwork. These inclusions were not imaginary but experiential artistic responses creating a powerful-layered world.

Like all things reaching its pinnacle subsides sooner or later, the booming European art market too hit a stalemate at the turn of 20thcentury, with the growing popularity of photography being one of the reasons of its untimely death. Soon the Indian artists were dispossessed both by the market economy and the private patronage that once so covetously had pursued them.

Their disappearances from public realm may today make for a fascinating read but that’s only too recent in the history of Indian Painting, and yet the study of Company Painting and their Indian creators have just begun.

Nilosree is an author, filmmaker