In the early 1990s, I went to the Swedish Television station in Stockholm to give an interview. My Swedish colleague and I just walked into the building without anyone even noticing us, and after a few minutes, I saw the news anchor reading the evening news behind a glass window.

It was my first few months in Sweden, and the absence of security checks surprised me the most. I asked my Swedish colleague what would happen if I came with four or five people and firearms, got into the newsroom, and declared myself the new ruler of Sweden.

He just laughed and said people watching the television would switch to the other channel for some time, thinking that a mentally challenged man had entered the TV station.

This short anecdote explains Sweden’s level of trust and confidence three decades ago in its democratic institutions. Someone may debate if that trust and confidence are still there, but it is for sure that entry to that same Swedish Television station building is not that easy anymore.

Some years ago, it was unimaginable for anyone to think of violent overthrow of governments in Western Europe or North America.

The coup was not part of the political dictionary in these countries. But that is changing rapidly. Far-Right extremist group’s attack on the US Capitol in January 2021 was not an aberration.

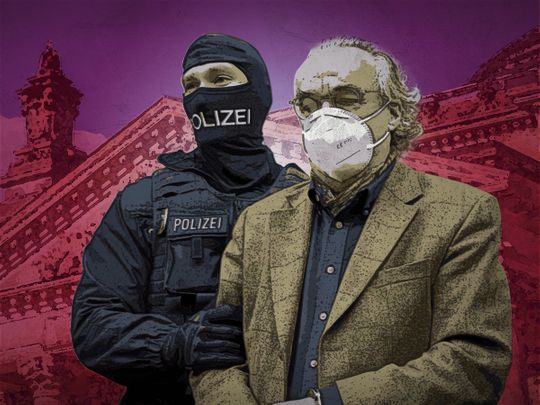

Last week, the German police arrested at least 25 extremists of the far-right Reichsbürger movement as they were at the advanced stage of a plot to overthrow the German government.

It is highly doubtful that the coup attempts will succeed in Western Europe. Still, it will be very irresponsible to underestimate these insanely militant far-right extremist groups and the dangers they pose to democratic institutions and the rule of law.

The arrested coup plotters in Germany are not semi-educated grungy characters; they are all educated professionals, including a judge, an aristocratic entrepreneur, former army officers, and former members of the police force.

They all know the political system and have a larger support base inclined to resort to violence. Political extremism has become a growing threat to Germany, and in 2021 alone, there were 33,476 politically motivated crimes recorded in the country.

In June this year, six months before the coup plot became public, the German Interior Minister had warned about the far-right extremism being the biggest existential threat to her country’s democracy.

The Institute of Economics and Peace prepares the annual Global Terrorism Index, which gives us an overview of global terrorism trends. The 2022 Global Terrorism Index reveals that while the West is witnessing a significant decline in religiously motivated attacks, there is a considerable increase in politically motivated attacks.

Taking far-right extremism seriously

In the last five years, the West has seen at least five times more political attacks than religious attacks. In 2021, there were 40 politically motivated attacks and only three religiously motivated attacks in these countries. Despite this trend, the political and security establishment has yet to take far-right extremism seriously.

Right-wing violence is not a new development in Europe. It has a long history, but its organised activities were contained for a period after the end of the Cold War. However, the continent has been experiencing a revival of far-right extremism for over a decade now.

In 2011, German police uncovered a far-right terror group called National Socialist Underground that had killed at least ten people. The same year, a far-right terrorist killed 77 people in a youth camp in Norway.

Since then, Europe has witnessed several extreme right-wing terror attacks. The refugee crisis in recent years has enlarged the support base of far-right parties in many countries and militant networks.

In 2022, far-right parties have come to power in Hungary, Bulgaria, and Italy and have increased their electoral support in Sweden and France. Their support base is expanding all over Europe, particularly in Germany, Austria, Poland, Netherlands, and Spain.

Europe’s far-right militants

This development makes it more difficult for security agencies to act against far-right militant groups because of their ties with legitimate far-right political groups.

Europe’s far-right militants, though the media often project the issue as domestic terrorism, have an extensive international network, even more, dense and diffusive than religious terrorism. At the same time, far-right terrorists have a robust domestic support base.

Far-right militant outfits in Europe are decentralised. They have different entry points to adhere to right-wing extremist ideology, but the common agenda is to end the liberal democratic political system of the country using unlawful means.

They use modern technology, particularly the internet platforms, in a more sophisticated manner to propagate their vicious ideology. They usually don’t adopt a mass killing strategy but opt for the targeted killing of key figures. They also don’t release press statements claiming their terror act.

The far-right terror groups have maintained a low profile by adopting these strategies. Still, they have become the most dangerous threat to the established values and norms of European politics and society.

One can hope that the uncovering of the coup plot in Germany will motivate the European countries to prioritise an adequate response to the threats they face from far-right extremists.