The more things change, the more they remain the same. 2023 has that déjà vu feeling. It’s a lot like 2018.

Five years ago, the BJP had emerged as the single largest party in Karnataka, failing to reach the majority mark despite anti-incumbency against a Congress government.

To add to that, the Congress outsmarted the BJP by bringing a JD(S)-led coalition government to power. Until then, it was the BJP that had been outsmarting the Congress.

By this time, there was that lingering question in the air: Aam Aadmi ko kya mila? What did the common man get?

In December 2018, the BJP also lost three states in the Hindi heartland: Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh, the last two of which were its bastions. The prime reason was discontentment among farmers.

There’s a similar whiff in the air after the BJP’s stunning defeat in Karnataka last month. Along with Himachal, these defeats cannot be simply explained by local factors and campaign mistakes. One ought to ask the difficult question: Is Brand Modi being overestimated?

Measuring enthusiasm, not just approval

Surveys of course show him far ahead of Rahul Gandhi and everyone else. When asked if you are satisfied with the Modi government, the resulting popularity ratings look comfortably stable.

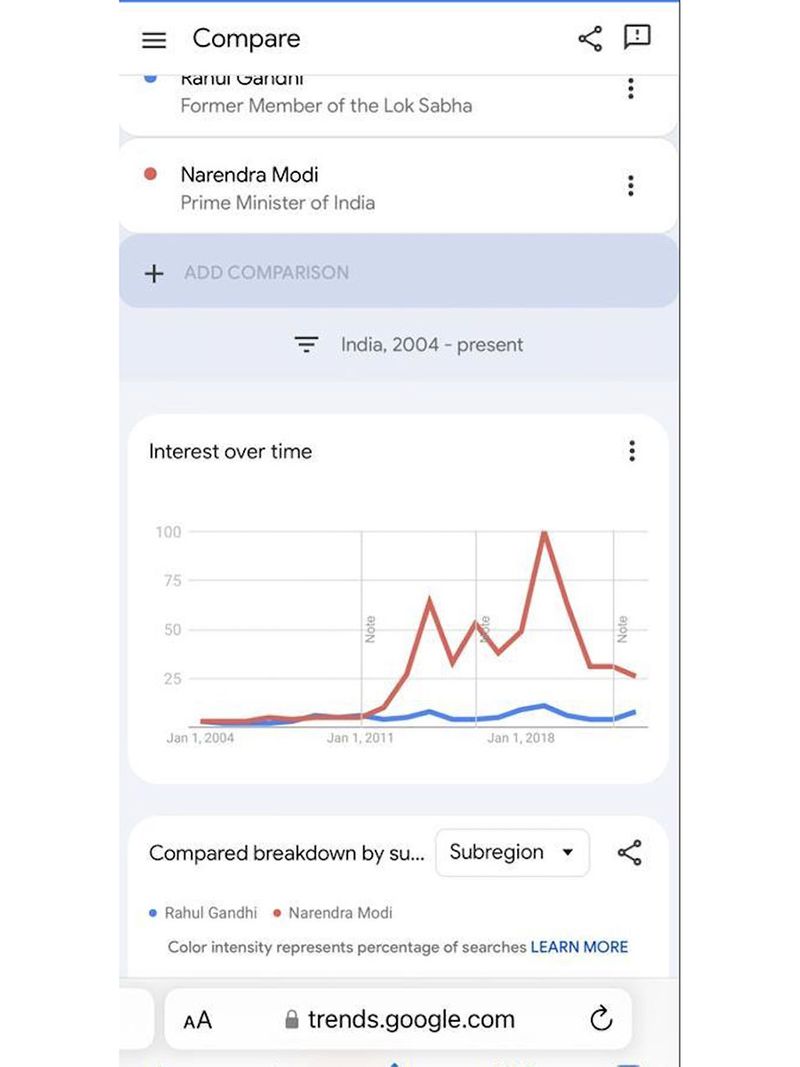

But if one looks at Google Trends, which measures public interest in a search topic, the picture is different. Mind you, this shows public interest in a topic, which includes both positive and negative public interest.

This chart shows that ‘interest’ in Narendra Modi has fallen sharply since the 2019 peak, and is in fact the lowest since 2014. Furthermore, on this trends chart, the distance between Modi and Rahul is the narrowest since 2014.

This does not mean that Modi is losing the next general election. It does mean that the public, including perhaps some of his own supporters, are waiting for something new from him.

Our brand is new

New-ness is a curse in politics. The public constantly wants something new from their politicians and governments. In the way that the public wants new models of the same phone, new designs from the same clothing brands, new movies and shows in the same series, the public also wants new narratives, new schemes, new images, new offerings from their leaders.

There is no dearth of new things coming from the Modi stable. There’s the new parliament, new polarising movies, new attacks on the opposition. What’s missing is a new welfare push.

Aspirations unfulfilled

The data from Karnataka shows the BJP’s sharpest decline in vote-share was in the poorer regions of a relatively prosperous state. Aspirational India, which became the backbone of Modi’s spectacular rise in 2014, is hurting. There’s more than enough economic data to show as much, even as official government data has become sparse.

Part of the Congress party’s campaign was 5 “guarantees” which were all freebies, including for the unemployed youth. In a country that has failed to create mass manufacturing jobs, freebies are inevitable. One man’s freebie culture is another man’s welfare state.

The top complaint across India today is the price of an LPG cylinder refill. It costs Rs1150, and some would say the increase has been in line with broader inflation. Except that it was the Modi government that pushed free LPG cylinders to the poor but now many can’t afford the refills. Their real incomes haven’t kept pace.

Modi-2 vs Modi-1

In 2018-19, the Modi government had tangible things to offer to Aspirational India. There were free cylinders, a big push for free housing, free toilets and finally, cash transfers to small farmers just before the 2019 elections. Without these, the skirmish with Pakistan over Pulwama and Ballot wouldn’t alone have been enough to give the BJP an impressive 303 seats.

In the Narendra Modi government’s second term, there isn’t a single tangible thing that’s new. Doubling down on the old things doesn’t impress voters. What’s new?

Covid is a distant memory, so good or bad handling of Covid is not going to impact the voter’s mind in any election. But the economic setback that was Covid for many, was not accompanied by the sort of compensatory welfare measures we saw in the West.

Some would say this was politically if not financially wise, as it has helped keep inflation in check. The free cash thrown at the public during Covid by Western economies has resulted in runaway inflation there.

The taste of the revdi

Yet, inflation in India did touch 5-6% and is only now coming down. Meanwhile, unemployment only increased in low-paying manufacturing jobs. Unemployment, poverty, inequality, inflation — all these have made life tougher for Aspirational India.

It is not enough to be one of the world’s fastest growing economies. If one has to win an election, the fruits of economic growth have to trickle down.

It is therefore obvious that Narendra Modi needs a new welfare push, and it feels like only a matter of time before it will come.

Despite the Prime Minister’s repeated comments against freebies (“revdis” or free sweets) since last year, that is exactly what Brand Modi needs to make his voters happy again. The taste of the revdi will be in the eating.