For now, at least, Iraq may have narrowly escaped another civil war. But the political crisis that sparked the clashes on August 29 continues to simmer, and unless the country agrees to an overhaul of the entire system, another — and probably a longer and bloodier — round of fighting is widely expected.

The crisis began shortly after the parliamentary elections in October 2021 as political parties failed to agree on forming a new government and appointing a new prime minister. The unique thing about the current crisis is that it pits Iraq’s most formidable, and heavily armed, Shiite groups against each other.

If the country fails to reach an agreement soon, there will likely be another round of fighting that could easily spiral into a devastating civil war that Iraq may have never seen before.

But on the other hand, the crisis represents a golden opportunity for Iraqi to reform a broken system that led to ethno-sectarian division of power, resulting in corruption and weak state institutions.

If independent parties, civil society groups and the army seize this opportunity, Iraq may finally get rid of the fake statehood that has had most Iraqis suffering from poverty, lack of basic services, subsequent corrupt governments since 2003 and an overwhelming influence of neighbouring Iran that has for two decades empowered corrupt and sectarian parties and politicians.

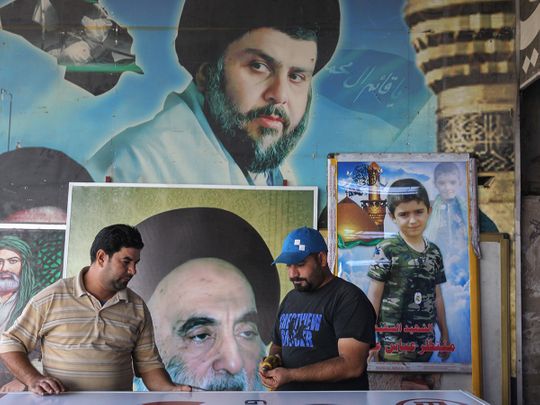

On August 29, followers of cleric Moqtada Al Sadr, upon the call of their leaders, turned the streets of Baghdad into a war zone. Few hours of clashes with his rival Shiite parties, led by former Prime Minister Nouri Al Maliki and popular militias leader Hadi Al Ameri, resulted in 21 deaths and hundreds wounded. A rush of internal and external mediations persuaded Al Sadr to end the clashes. Tension, however, remains high and the situation could explode any time.

Political limbo

Al Sadr’s party won 73 seats in last year’s polls, more than other parties in the 329-seat parliament. But Al Maliki and Al Ameri succeeded in uniting other Shiite parties in a coalition with close to 150 seats thus denying Al Sadr the ability to nominate the new prime minister.

Angered by his rival politicians’ manoeuvre, which he argues was driven by Iranian designs, Al Sadr resorted to the streets calling on his followers to turn the tables on those parties that have overseen the destruction of the Iraqi state in what is widely described as the biggest embezzlement of public funds in the region’s modern history.

President Barham Salih, in widely reported comments during last year’s polls, said $150 billion of oil money “had been stolen and smuggled out of Iraq in corrupt deals since the 2003.”

International groups have accused senior officials of Iraq’s subsequent governments of taking part in the embezzlement schemes, paying off their way into power and keeping a steady flow of voters. Al Maliki’s eight years of power in the past decade has been described as the most corrupt in the 19-year period since the fall of the Saddam regime in 2003. Iraq, despite its vast oil, water and minerals wealth, has one of the biggest poverty rates in the world.

Call for stable, safe Iraq

The caretaker Prime Minister Mustafa Al Kadhimi this weekend said the current crisis is Iraq’s “most difficult political crisis since 2003.” He urged all “to find solutions and overcome the crisis in order to pass towards a new stable and safe Iraq.”

But it is doubtful that his comment would persuade the dominant parties to come to an agreement. The streets may be calm today but come October, those streets will likely see hundreds of thousands of anti-regime protesters to mark the anniversary of October 2019 protests which civil society groups say were put down by Iran and its Iraqi proxies, led by Al Ameri’s Hashd mobilisation forces. This time the protesters will be joined by Al Sadr’s large base of support.

Iraq, therefore, is likely on a crucial date with unprecedented protests that will expectedly call for a complete overhaul of the rotten system.

Iraq’s oil revenue in the first half of this year exceeded $60 billion. Its revenue from the religious tourism is even bigger. Unlike other countries in the region, it enjoys the luxury of having two major rivers and countless lakes.

It is an agricultural haven and boasts one of the most educated and skilled population in this part of the world. But in the past 40 years, subsequent regimes have squandered this massive wealth through wars, corruption and mismanagement.

Iraq today has an opportunity to build a modern functioning state that should enjoy a high level of living standards, compatible with its rich resources. The current crisis, may be a dangerous one, but can represent an opportunity for the Iraqi people to take their country back.