At least as old as civilisation, the land is a carrier of secrets, grandmother’s recipes, and truths, even those stretched and violated. Like a stream that finds an opening in a crack, it is both the story and the storyteller.

Plunderers, colonialists, rulers, refugees, it watches the silent march of time, manifesting in forms like the mighty tree that spreads its branches to shade and shelter.

Land is not just the physical — a fistful of soil or the ancestral house where generations shared food on the table. It is as much the intangible that breathes life into nostalgia with the ferocity of a newborn’s cry.

At its core is belonging, a word so powerful yet shrivelling in a conflict-laden reality of those bereft of both a past and a future.

So, is land, say for a Palestinian, his refugee tent, or is it what surrounds him — the rubble of Gaza with remains of his family?

On the other hand, for immigrants hoping to better angry oceans by clinging to overcrowded boats and surviving or perishing in just the clothes they wear, the promised land must weigh more than what is left behind.

Hope tussles ferociously with a boundary as in the cult classic Shawshank Redemption, ‘I hope the Pacific is as blue as it has been in my dreams. I Hope.’

A generation struggled

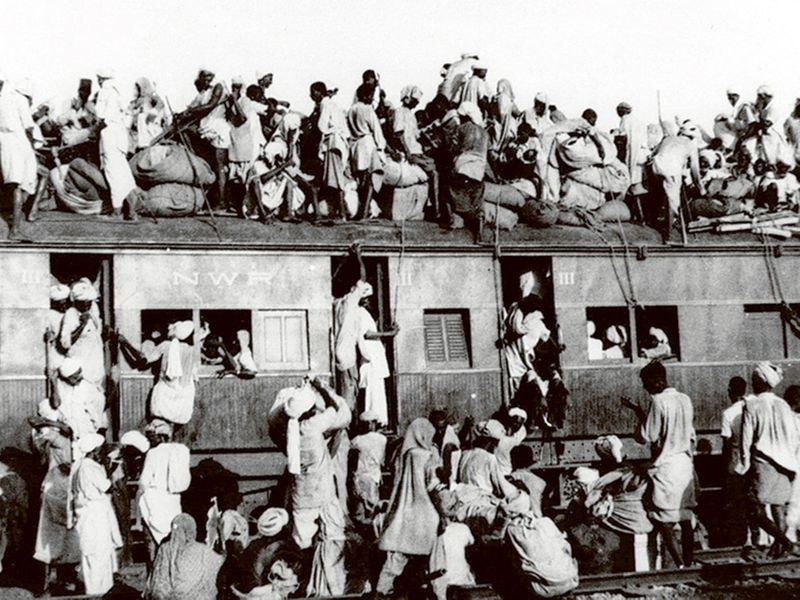

77 years ago, 14 million people grasped that same faith and severed their roots, even if tenderly, in the largest human migration, India’s Partition. In the north, the people of Punjab who were hit the hardest left behind a community of shared past and culture to set up a new home barely hours away.

Through the contemporary lens as those in hindsight, the question arises, is land ambiguous when it comes to pluralism? Have we been blindsided all along?

Separated on religious lines, the jagged line that divided their land into two was not strong enough to wipe all its scent. Reminiscent of a stubborn tap that leaks a drizzle of water, in these homes longing dripped.

It was in every day, in the aroma of food cooked or a kite outside a window in spring. A generation struggled; how much should they let go when forgetting itself is not easy?

Is it tougher to remember or to forget, its answer perhaps has no shades of black or white. Gyanendra Pandey writes of India’s Partition survivors, ‘They had to struggle to overcome new fears, to gradually rebuild faith and trust and hope and to conceive new histories — and new memories that are, in some reckonings, best forgotten. What is the point of telling today’s children about these things? (they say)’

Chasing a well in a desert

Is land then also a burden, both through memories and inheritance of the individual and the collective? Does it equally build resentment among those who feel chained, yearning to step outside its confines and partake of nomadic humanity chasing a well in a desert, and those who stay back?

Punjab was traditionally India’s green basket shepherding its agriculture revolution, today with the youth migrating to countries like Canada in search of a new way of life, the ageing population is left behind to till the land.

The whirlpool slows down to remind us of our origins, like the pandemic’s deadly second wave when even crematoriums in Delhi ran out of sympathy. In times like these the land stays silent, its edges burnished by our tears as it admonishes those who abdicated.

Its anger is felt thousands of miles away for survivor’s guilt is also a disease. Partition, pandemic, and Palestine all have one thing in common, it has extracted a heavy price from those who made it to the other side.

Almost 40,000 people have reportedly been killed in Gaza since Israel’s offensive, a majority of them women and children.

For Palestinians spread across the globe affirming Gaza as their land forever, navigating and processing loss is directly proportionate to their identity, for themselves, and the outside world. It is no different in any other place of conflict.

We are the land

Beleaguered by wars and the tempestuousness of politics — the latter treats boundaries of nation-states as inconsequential — Gaza holds on, challenging the Western slant of history, ‘when we listen to a tale, we need to take into account the teller.’

Land defies all attempts to box it in and with history, the ink to its pen, writes the story. Meanwhile history, irrespective of who records it, has one common thesis. Defiance and perseverance are layered deep within.

A question arises, through time’s passage, is generational loss a given? An American-born Afghan poet, a British-born Indian doctor, or a Turk who plays football for Germany, are all global citizens but are they also a step closer to being people of nowhere land? Do roots define land or is land itself a transformational definition?

In Robert Frost’s famous words, ‘There are two forks in the road,’ the dogma that is their ancestors’ land clashes with the culture of a place called home. It could be a language disconnect or a missing social construct but wrinkled faces who smell that scent will wonder, was it always this easy to lose?

Raw and exposed, the land tests, as in Gaza or a village in India where a family chose to migrate from across the border only to be ostracised for their religion 75 years later.

As Gaza hurts or a refugee boat sinks, is land a privilege? Like its trail, the questions are endless. There is one certainty though, its pain and glory are both ours.

We are the land.