Shahryar, a mighty king learns of his wife’s amorous connect with a slave, promises to avenge it on all women he would marry hence. A night of conjugality, the next morning would turn a doom for the newly wedded bride succumbing to an untimely death designed by their husband.

Enters Shahrazad, the vizier’s daughter, clever and brave determined to put an end to these murders. She comes up with a plan, to narrate a story every night for the next 1000 nights, leaving the king curious to know the end of these tales, consequentially delaying Shahrazad death.

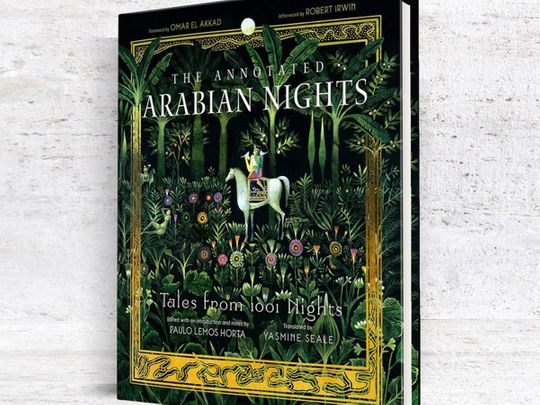

Here is a woman storyteller who can spin stories like unending silk carpet of spectacles, wonders, and burlesque form the grounding adventure for the newest annotated, brilliantly illuminated ‘The Annotated Arabian Nights:Tales From 1001 Nights’ (WW Norton & Co ).

Perhaps the biggest irony in the world of literature, The Arabian Nights had been regretfully credited to British antiquarian Richard Burton and primarily to another French translator Antoine Galland whose volumes of stories were published between 1704 and 1717. Europe showered fame on Galland crediting him a literary genius, denoting him wrongly as the creator of The Arabian Nights.

However the reality was distant from what Europeans thought it to be.

With no single definitive manuscript in Arabic and no defined author, The Arabian Nights owe its roots to rich folklore traditions of Arab lands, a storytelling culture spawned out of coffeehouses, markets and souqs of cosmopolitan Cairo, Damascus, Aleppo pollinated through many sources brought over from Persia and India.

Interestingly the best known tales like Aladdin or Alibaba and Forty Thieves or Prince Ahmed and Pari Banu has no records, thus emphasising of their raconteur qualities.

To that the most acceptable ownership of these popular stories goes to a Syrian man called Hanna Diyab, a professional storyteller from Aleppo of early 1700s, who invented or recycled them and yet remained in complete anonymity for next 270 years.

The Hanna Diyab connect

A packed coffeehouse somewhere on a busy street in Aleppo, Diyab was heartily narrating a saga. The audience, mostly a mix of locals and travellers were lapping it all, some alert to what’s coming on next, others languidly, reclined on seaters, absorbing every word of the young storyteller dressed in his local attire of an upper and an inflated loose pant as the air smelt thick of caffeine.

During one of these storytelling sessions, Diyab met a French man called Paul Lucas, an archeological treasure hunter scouting through Arab lands, dispatched by king Louise XIV of France. The later had been desperately looking for an interpreter cum associate, who could team up with him.

Lucas’s offered Diyab a role of a guide for the rest of his trip and in return he would get Diyab a coveted job at the Royal Library of Paris. The Syrian storyteller accepted what seemed a lucrative offer, as they embarked on a long journey reaching Paris in the fall of 1708.

All this and more was recorded in a memoir which Diyab wrote after returning from Paris to Aleppo in late 18thcentury.

Life in Paris was an impatient wait for Diyab, hoping Lucas to fulfill his promise. Soon he would meet an elderly literato called Antoine Galland. That was on a Sunday in the summer of 1709. Over the next few sessions Diyab had narrated Antoine15 amazing stories including the story of Aladdin.

Hardly did the men sense how these spontaneous narration would eventually change the dynamics of world’s most popular literary work.

Galland was an old player; an antiquarian at the royal court of France, a scholar, librarian and a traveller who had spent his time in Arabian countries as well as in Constantinople. As luck would have it, when he met Diyab he had ran out of his bank of stories having previously published 7 volumes, tiled as “Les mille et une nuit” in French drawn from the medieval Arabic manuscript ‘Alaf Layla Wa Layla’.

Galland began preparing for his next, appropriating what Diyab had described. Strange as it may sound, Galland did not credit Hanna Diyab other than a few sporadic mentions in his personal diary.

Playing it in 2022

With the new annotated and translated Arabian Nights titled ‘The Annotated Arabian Nights’ published by WW Norton, some of these gaping gaps have been addressed. To that a just and fair contribution, breaking the myth of French genius read European creator is achieved.

The current volume has inspiringly translated by French Syrian poet, translator Yasmine Seale and brilliantly edited by scholar Paulo Lemos Horta has more than one goodness to highlight.

Not only it is a telling of world’s most spectacular stories of wonder, dreams, magic and reality packaged in the most intimate translation, it is also a decolonized viewing of the arabian roots of these stories, detaching it from its overwhelming burden of European-ness.

Commenting on the new volume’s tone Paulo Lemos Horta, scholar and editor, faculty at NYUAD (NYU Abu Dhabi) says, “The most widely available version of the Nights out there in English is by Richard Burton, reprinted in the Modern Library Classics series, a handsome Barnes and Noble edition, and countless other online and print editions. That 1885 version is burdened with Burton’s own prejudices, which he interwove and interpolated freely. My goal was very much to move beyond past versions burdened by the prejudices of the translators.”

Brining back Diyab’s signature, a more nuanced, culturally intimate Arabic storytelling was an intent for the translator and editor.

Horta affirms “It is the reason for this new volume, to restore his tales, first published in the French translation, among them, “Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp,” “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves,” “Prince Ahmad and the Fairy Peri Banu,” “The Enchanted Horse,” and “The Night Adventures of Harun al Rashid.”

Because of this mandate to publish the Hanna Diyab tales alongside those of the original core, I sought out a translator who could translate with equal poise from French and Arabic, Yasmine Seale”.

For the starters, Seale is an acclaimed French Syrian poet and translator, the first woman to translate Nights. The other first credited to the volume is its inclusion of stories around female protagonists like Marjana, Pari Bano and Parizaad all smart and incisive women, earlier shadowed by their male counterparts, courtesy orientalist nature of earlier translations.

Horta and Seale reverses this. Seale also reclaims the Persian name for the vizier’s daughter; Shahrazad, the narrator of the Nights instead of much used Scheherazade.

Horta notes “And working with the same editor who commissioned Emily Wilson’s Odyssey, the first English translation by a woman, I reasoned the Nights tales, more focused on tales of women versus men, might benefit even more from a first female translator in English.”

Through Seale’s sparkling, visually rich translation and Horta’s opulent annotations one is exposed to splendorous storytelling grounded in the culture from where it originated minus its ethnographic lens.

Interestingly this edition of Arabian Nights show how these stories continued to be amalgamated right from its first collation in Bagdad way back in the times of Abbasid Caliphate imbibing imprints of imagination, localization in its journey while being time and again shared and recycled in public places, coffeehouses, markets of Aleppo, Damascus, Cairo till it landed on the other side of Mediterranean in the uninformed imagination of Western audience.

This edition of ‘The Annotated Arabian Nights’, returns to a full circle.

‘The Annotated Arabian Nights : Tales From 1001 Nights’ (Hardback)

Yasmine Seale (Translator), Paulo Lemos Horta (author of Introduction and Editor) published by WW Norton & Co

Nilosree is an author and filmmaker