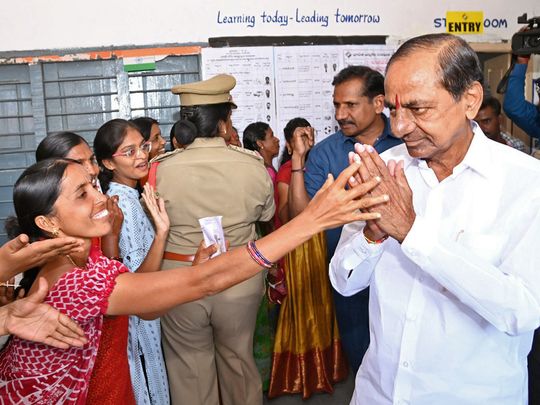

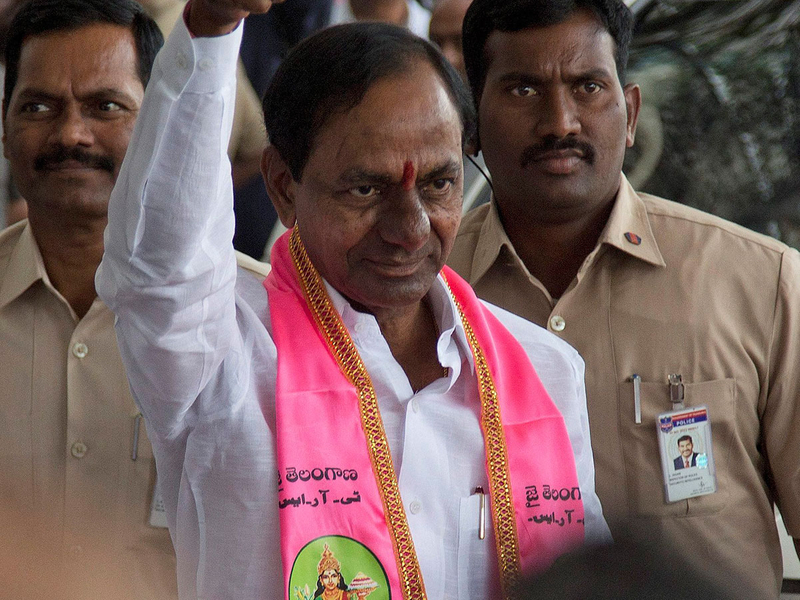

The state of Telangana was carved out from Andhra Pradesh in 2014, after a decades-long statehood movement. The face of the Telangana movement, Kalvakuntla Chandrashekar Rao, won two terms as chief minister, in 2014 and 2018.

If in 2014 he won because voters credited him with wresting Telangana statehood, in 2018 it was because of his welfare schemes. Travelling out of Hyderabad, all one could hear in 2018 was “Rythu Bandhu”, the flagship welfare scheme that gave farmers a direct cash transfer.

The main argument in favour of Telangana’s statehood was that it was the poorer, neglected part of undivided Andhra. Statehood, and nine years of KCR’s Bharatiya Rashtra Samiti rule have resulted in undeniable prosperity for the state.

Apart from the welfare schemes and the dams that have irrigated dry lands, there’s great growth and construction everywhere. Driving from Hyderabad to Gajwel, the CM’s VIP constituency, all one sees is smooth roads and construction, and ads for villa plots on sale. The IT hub in Hyderabad looks fancier than ever. Urbanisation is at full speed.

This visible growth reflects in data. In 2023, Telangana’s per capita income became the highest among large states, marginally inching past Karnataka.

Change is in the air

And yet, there’s a good chance KCR could lose the Telangana assembly election, for which results will be out on December 3.

The sentiment of change is in the air. But why? Why would people want to change a government that has undeniably made them more prosperous? A government that gives them both freebies and development?

“It’s been ten years,” comes the reply. The rational reasons come later. The word “change” is emphasised like people want to take a holiday because they’re bored of their daily routine. They want “change” like wanting to buy new shoes not because the old shoes have come apart, but one is bored of them.

Do you think people are bored of KCR? Absolutely, comes the reply, especially from people who are changing their voting preference from KCR’s BRS to Congress.

The rational reasons come later: they accuse “the family” of becoming arrogant and inaccessible, they complain of favouritism and corruption in the execution of various schemes, they complain that benefits go mostly to one caste, one kind of elite that came about in 2014.

Poor execution in two schemes are particular pain points: “Dalit Bandhu” and “2BHK”.

The Dalit Bandhu scheme promises a grant of Rs10 lakh to Dalit families to help start a business, and the 2BHK scheme promises a 2-bedroom house to the poor. In both cases, people complain that there was corruption in their allotment.

Such issues are typically what are clubbed under the umbrella of “anti-incumbency”. As is the unpopularity of sitting BRS lawmakers, many of whom KCR did not change this election for their ‘loyalty’.

Narrative fail

All of these issues could have been addressed by managing the political narrative. But the BRS was overconfident in its second term that its hold over the people was unshakeable.

This overconfidence led them to change the name of the party from Telangana Rashtra Samiti to Bhartiya Rashtra Samiti, targeting national politics now that they had a complete hold over the state. Like HD Deve Gowda in Karnataka and Mayawati in Uttar Pradesh, projecting national ambitions did not help KCR in Telangana. Replacing ‘Telangana’ with ‘Bhartiya’ created a distance between him and his people.

KCR’s biggest mistake is that he didn’t reinvent himself and his party’s narrative at the state level. The people always want something new, something fresh. Just look at how phones, cars, shoes and clothes all come out rebranded, refreshed every year.

KCR is going through what Shivraj Singh Chauhan did in Madhya Pradesh in 2018: it’s not anger, it’s fatigue.

Old wine needs new bottle

This makes you appreciate how prime minister Narendra Modi reinvents his image and narrative every 2-3 years, without going against the vote values of his brand. To his credit, even Rahul Gandhi recently managed to give himself a slight makeover with the Bharat Jodo Yatra.

The lack of such reinvention is why KCR finds himself in a soup.

How much of this “change” sentiment can convert into votes, nobody knows. There are elections when a leader manages to survive despite a sentiment for change (Nitish Kumar in Bihar 2020, Mamata Banerjee in West Bengal 2022). This is made possible through political management: cadres, resources, ground presence.

But there are elections when the change sentiment is like a tsunami: Punjab 2022, Karnataka 2023, Chhattisgarh 2018, and so on.

Whether BRS wins or loses in two days, the need for a reinvention will not escape KCR.