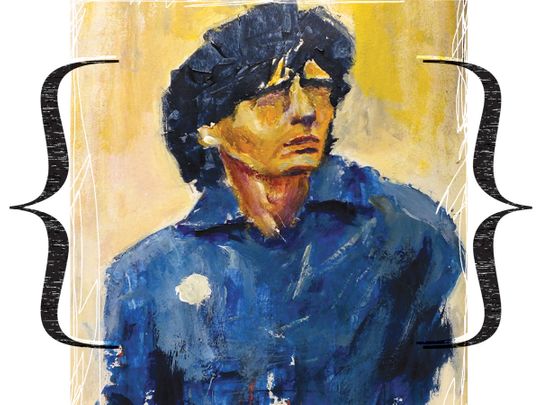

For me, and I assume for millions of others of football fans, the 1994 World Cup in the US was an emotional rollercoaster. Because of one man — Diego Maradona. As the competition started, I was ecstatic to learn that the best player to ever walk the pitch was in the Argentine line-up. Football fans couldn’t ask for more. He was there to avenge the humiliating defeat of 1990 when the Germans literally stole the show in the final. The teary-eyed Maradona’s image at the end of that game broke the hearts of millions around the world. Few managed to hold their tears, I think.

But my actual thrill was totally for another reason. As a teenager, Maradona was my hero. I never missed his games — with Barcelona and then Napoli and with the Argentinian national team, of course. Therefore, it was extremely devastating to see the larger than life lose it all post the 1990 defeat.

In 1991, while still playing for Italy’s Napoli, Maradona was tested positive for cocaine and therefore banned from all football for 15 months by the world’s football governing body, Fifa. All of a sudden, there was hardly any news about his football genius. Instead, it was a daily dose of heartbreaking reports about his drug and alcohol addiction. For a good part of the early 1990s, he was the bad boy of sport — the cocaine addict, the party animal frequently dragged to court for dodging alimony. He seemed to have thrown his life, and an out of this world talent, away. He was done. And for me, football didn’t matter any more. I was done, too.

Then, there he is in 1994, donning the captain sign as Argentina faced Greece in their first match of the tournament. It was like the redemption we all for years had hoped for. Sure, I was overwhelmed. But with some scepticism. Will it be 1986 Maradona who elevated us to the skies with his magic or the 1990’s who broke our hearts? The answer came an hour later.

His incredible 60th minute goal, a Maradona signature goal — a left-foot shot at the top left corner of the net, sealed it for me. He was back and at his best. Argentina went on to win 4-0. The second game was against Nigeria. The Tango boys won again. It was 2-1. Maradona was not particularly exceptional in that game but hey, he was 34 years old. Give him a break, I thought to myself.

Second fall of the giant

What came after that game was the moment I could have prayed to have never happened. The second fall of the giant. The crushing news again. As part of the tournament random dope testing rules, Maradona tested positive for ephedrine, a stimulant allowed in Europe but banned in the US. He was thus banned from all football for another 15 months. Brazil, Argentina’s football nemesis, went on to win that cup. It was the end of football for me — again!

It has been said that if Maradona was ‘the God’ of football, Eduardo Galeano’s book Football in Sun and Shadow was its ‘Bible’. Galeano, the Uruguayan literary giant who died in 2015, was one of Latin America’s most ardent leftist thinkers.

In his trilogy, ‘Memory of Fire’, considered one of his greatest works, he tried to “rescue the kidnapped memory of all America”, as he put it. It was an attempt to redeem the forgotten history of the continent, for long suppressed and also distorted by western colonialism.

A genius who defied logic

In his football bible, Galeano argues that football is not only a sport, and Maradona was not just a football player. He was a genius who defied the logic of science and probabilities, a philosopher who understood the true meaning of the game and that it was not limited to the pitch, a revolutionary adored by millions of nameless people and faceless masses, a magician who made us all believe in magic, but at the same time, he was just a man — a beautiful but vulnerable man who withered like a rose leaving behind a wonderfully scented memory.

Maradona was the mad king of the game who not only exceeded the limits of football but elevated the game to represent something far beyond the sport. Every time Maradona walked the pitch, he lit a flame of hope for those millions of marginalised, destitute, oppressed, and bullied people all over the world.

Galeano, the ever-leftist warrior against ‘Western capitalism onslaught’, which he most probably might have regarded as the main cause of at least some of Latin America’s misfortunes, has likely found in Maradona the champion that gave people of the continent pride. Born in the downtrodden slums of Buenos Aires to a poor single mother, Maradona was an inspiring model that resonated with millions of young people in Argentina and other Latin countries.

Historic goals

His two historic goals against England in the 1986 World Cup was the triumph Argentina looked for, following its humiliating military defeat four years earlier in the Falkland War at the hands of the British. Let’s not forget, England was the leading colonial power for more than 300 years. Those two goals, especially the second one — dubbed ‘the Goal of the Century’, was Maradona’s attempt to redeem his country’s pride, Galeano would have thought.

For me, that moment is where my selective memory of this football genius stops. Unconsciously, perhaps, my brain refuses to register the memories of Maradona post-1986. it cannot fathom the crushing fall of the king — the end of the age innocence, the end of romanticising football in 1994.

I love Maradona, the humanitarian, the leftist activist, I enjoyed his pictures with Castro. (He was active against poverty, war, and oppression. And against the unilateral US wars in the past two decades). But my hero was the kid from the slums who beat all the odds to win football trophies, and most importantly, our hearts.