Whitehaven is, as they would say in rural places in the UK, “the back of beyond”. You’d only ever get there if you were going there. It’s on the end of the road, a good 60 kilometres to the northwest off the main M6 highway that heads from Birmingham, England’s second largest city, north to Glasgow, Scotland’s largest population centre.

Few now ever go to Whitehaven. It’s a small port town that a brave 23,000 or so call home, tucked between the hard shoulder of Cumbria and the armpit of the Scottish border.

Sure, back in the day, it was a prosperous little place. As the 16th Century rolled into the 17th, it was the second busiest port in England after London — the leaving point for ships heading over the top of Ireland, out into the Atlantic to the 13 colonies that were quite happy then under English rule.

Coal then made it rich. Coal died, and so did the town, with the only work locally in a nuclear plant and waste recycling facility. A few work out of town, in Barrow-in-Furness, in the shipyard that builds and maintains the UK’s nuclear submarine fleet.

So, when a local company said it wanted to develop a new mine four years ago, for coking coal for the steel industry, the good folks of Whitehaven got more than a little excited. And so too did the environmental lobby, shocked that the UK would even consider developing a site that would add to global warming, carbon emissions and all of that.

Besides, the UK was a world leader, wasn’t it, when it came to the fight against climate change? After all, didn’t its delegates at every level just lecture the rest of the world on the need to get rid of coal, telling India and China and other developing nations that they had to turn away from the black rock that made Victorian and Edwardian Britain a global industrial power.

After years of dispute over planning, Levelling Up Secretary Michael Gove on Wednesday waved through plans for a new mine in Cumbria, which would provide coal for steelmaking rather than power generation.

But, if you know one thing about the Brits, they abide by the mantra of “do as I say not do as I do”. Or, given Whitehaven’s seafaring past when Britannia ruled the waves, now it’s Britannia waiving the rules.

Or, to spell it out in a single word: hypocrisy.

UK’s green credentials

The decision paves the way for 500 new regional jobs in a town and region where only the hardiest businesses can make it through a winter of very high energy costs. While the economic hit might be welcome, the environmental one will reverberate for months to come. Overnight, the approval of this coal mine to fuel steel furnaces has melted years of work trying to forge the UK’s green credentials.

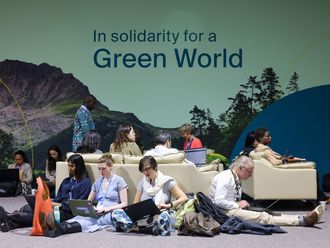

The approval comes a year after the UK hosted the COP26 climate talks just over the border in Glasgow, when it lobbied other countries to “consign coal to history”.

The developer, West Cumbria Mining, naturally says it’s delighted with the approval, and said it planned to create “the world’s first net zero mine” — which in itself seems like the ultimate environmental tautology. It plans to offset the emissions from the construction, mining and domestic transport phases.

The mine could release as much climate-heating pollution as putting 200,000 extra cars on UK roads, analysis by think tank Green Alliance says.

Besides, even the steel industry says that there’s little demand for the very product being clawed from the black rock under Whitehaven.

British Steel doubts it has the right composition, while Tata Steel plans to shift away from coal to cleaner methods within ten years, and the wider steel industry is looking at greener technologies such as hydrogen, to make its product meet carbon neutral levels. Even if the coal from Cumbria was to be used in Britain, it would displace imports from Kentucky and Pennsylvania, and not from Russia — obviously a hot political potato right now

A fractious lot

There are a couple of things that might stop the mine from ever going ahead.

For starters, Gove’s decision is highly politically charged, and will surely meet opposition from within Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s own Conservative party.

They are a fractious lot, with a third supporting the former PM Boris Johnson. Sunak is looked upon as a defeated and default leader — losing to Liz Truss in the race to replace Johnson, a default choice because Johnson pulled out of the race to replace her, opening the door to the current occupant of Number 10.

This environmental cause might find favour with those in a rebellious mood in the House of Commons.

And then there’s the court route.

Lawyers for Friends of the Earth, which opposed the application during the planning inquiry, are considering legal action. The UK, after all, is in a legally binding international treaty on climate change.

Ding. Ding. Ding. That’s the sound of alarm bells. Yes, the UK is also a signatory to a legally binding international treaty on withdrawing from the European Union.

Sunak’s own government is passing legislation to overrule that when it comes to the little matter of Northern Ireland. If that bill passes, the judges who hear the Cumbria case will then have a legal precedent to see how the UK really doesn’t have any legal obligation to meet any international legal agreement.