Just as Europe gets over the peak of the corona health crisis, a second major ‘shock’ could be on the horizon. For a new Brexit crisis is brewing between London and Brussels that could see talks collapse in June after the latest session ending on Friday made little progress.

Last week, EU Trade Commissioner Phil Hogan warned the United Kingdom “to get on with the job” if there is to be a deal by the end of the year. And he said next month’s stock-take talks would be “critical”.

By common consent of both sides, hardly any serious advancement has been made since negotiations for a new trade deal began in March. There remain big gaps in positions, including over the EU’s demand for guarantees of fair competition (so-called ‘level playing field’ provisions) that have been rejected by the United Kingdom; guarantees on personal data protection; plus the UK’s request for continued access to the EU police and border database, the Schengen Information System.

While the EU needs to show more compromise too, it is the UK government that seems most inflexible in its approach. This includes ruling out (for now at least) even the possibility of an extension to the transition period at the end of the year, even if Brussels asked for this.

Delivering a smoother departure now needs clear, coherent, and careful strategy and thinking on all sides so that London, Brussels and the EU-27 can move toward a new constructive partnership.

There are at least three interpretations of the UK’s dogmatic stance. First that it is tactical and designed to convince the EU that London doesn’t mind if it gets a deal or not in the hope that a better deal then emerges on UK terms; and second, that Boris Johnson’s team would prefer a ‘no deal’ outcome which signals maximum political distancing from the EU to the outside world but then is somewhat softened by a series of sectoral ‘side deals’ in areas to which the UK gives priority.

A third explanation is that it is tactical too with the UK team having no intention of signing up to the likely terms on offer from the EU, and that with the recession accompanying the coronavirus crisis (the worst since 1707 the Bank of England forecast on Thursday), leaving on WTO terms is a less daunting prospect that it appeared before the pandemic hit. It is noteworthy here that London has already said that it has re-commenced preparations to end the transition period for no trade deal on WTO terms.

Former Irish minister Hogan leans toward the third explanation. He said last week that “UK politicians and government have certainly decided that Covid is going to be blamed for all the fallout from Brexit and my perception of it is they don’t want to drag the negotiations out into 2021 because they can effectively blame Covid for everything. There is no real sign that our British friends are approaching the negotiations with a plan to succeed”.

'Bare bones' UK-EU trade agreement

That startling candid assessment has, of course, been rejected by Downing Street. Yet, unless the United Kingdom drops its doctrinaire position that there can be no transition extension, Hogan’s views are a plausible assessment of the government’s motivations given the short amount of time now to reach a deal.

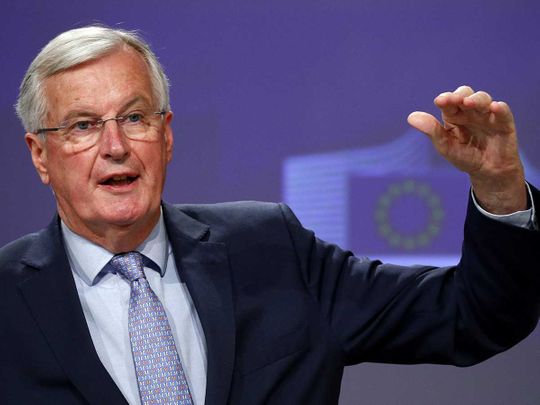

Even before the corona crisis began, the ten months period from March to December was not likely to be nearly long enough to agree more than what Chief EU Negotiator Michel Barnier has called a “bare bones” UK-EU trade agreement. And not the kind of deep trade deal promised by some Brexiteers in 2016.

All in all, with the political mood music between London and Brussels so bad, there is a growing possibility of what even Brexit Party Leader Nigel Farage has called a new “crisis” next month by which time both sides need to decide if there will be an extended transition into 2021. So, there is growing pressure on both sides with the prospect of a no-trade deal Brexit raising its head again.

If that outcome happens, especially in the absence of any sectoral side deals, both Brussels and London would probably need to return to the negotiating table in the months that follow, but with a new set of incentives. Such discussions could take significantly longer in this scenario than if Johnson were to secure a deal in the transition period.

Moreover, outside a transition, the negotiating process could get significantly harder, with the same tough trade-offs as before. One factor that may make concluding a deal significantly more difficult is that — outside of transition which requires only a ‘qualified majority’ of states to ratify — EU-27 unanimity would be needed. Indeed, the possibility of just one European state blocking an agreement remains a key risk.

The stakes in play therefore remain huge and historic, not just for the United Kingdom, but also the EU which could be damaged by a disorderly no-deal Brexit. Delivering a smoother departure now needs clear, coherent, and careful strategy and thinking on all sides so that London, Brussels and the EU-27 can move toward a new constructive partnership that can hopefully bring significant benefits for both at a time of corona crisis and wider geopolitical flux.

— Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics