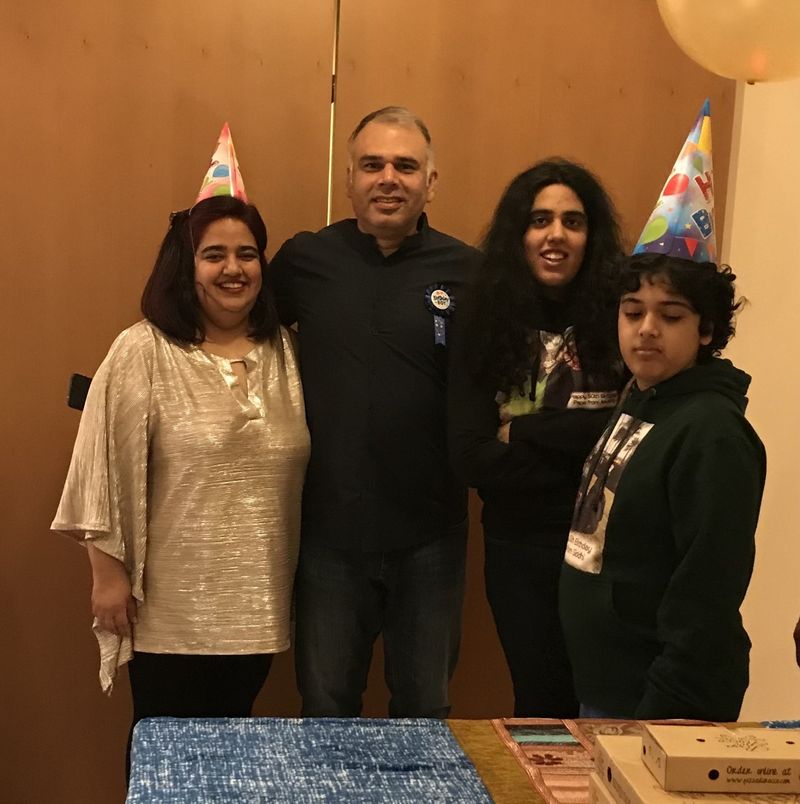

“I hate corona,” says Dubai-based school child Ameya, who turned nine this November.

Like millions of kids across the world, Ameya has borne the brunt of staying indoors and socially isolated for several months due to the deadly virus.

The initial months of lockdown were scary for her. When she had a stomach pain and fever in April, she went crying to her mother, Jismy Shanavas, and asked: “Did I catch the coronavirus mum? Am I going to die?”

At the time Jismy and her husband Shanavas Mohammed - who also have a 13-year-old daughter, Neha - were actively involved in helping several people under quarantine with food, and used to talk frequently to family members and friends about being careful with regards to the virus.

“When Ameya became sick and got worried that she was going to die of COVID-19, we realised that we might have been talking a lot about what is happening around in front of the kids,” says Jismy.

It’s virus-related stress like this that health professionals worry could have a lasting impact on children for years to come. Even as hopeful news of vaccine breakthroughs and approvals ripple across the world, there is concern that the upheaval experienced during delicate periods in kids’ development could potentially lead to a generation of young adults still suffering from the fall-out of their pandemic trauma in five to ten years’ or more time.

Luckily Ameya’s fears faded away with some compassionate explanation from her parents, who were sure to shelter her from sensational news and any further “scary stuff” regarding the virus going forward. But how has the pandemic affected other children, why and how could there be a long-term impact, and is there anything parents can do to mitigate this?

Why children are more vulnerable to COVID fallout

As the first wave of people begin to receive the coronavirus vaccine, there finally seems to be light at the end of the pandemic tunnel. But while as adults we may already have the emotional tools to be able to pick up from where we left off before the pandemic with our mental health relatively unscathed, for children it can be more complicated.

“Children are developing individuals with countless factors affecting their growth and development, from genetics to parenting, schools, environments, nutrition, good habits of sleep and health,” says Sam Hassan, lead author of a study by Mediclinic Hospital Dubai on the impact of COVID-related home confinement on children, published in the American Journal of Paediatrics.

Children are particularly sensitive to sudden changes in routine, and the upheaval following the onset of COVID-19 and the subsequent restrictions will have inevitably affected most aspects of children’s lives, says Dr Hassan. “Trauma of this kind may endure for a long time with negative consequences that may manifest later on, even up to adult life.”

The results of Mediclinic Hospital Dubai’s survey of 650 parents show the extent of pandemic home confinement on children. “More than 72 per cent of children were reported to demonstrate behavioural problems which were not there before the lockdown,” Dr Hassan told Gulf News. “More than half were reported to have new mental distress such as anxiety, while 14 per cent were affected financially due to one or both parents losing a job or being on reduced pay.”

Hyperactivity and inattentiveness were found in 36 per cent of the children, while loneliness and depression were reported in 18 per cent of the kids.

And when asked if home confinement due to COVID-19 may lead to long-term impacts such as boredom, fear of infection or stress, 63 per cent of parents answered in the affirmative.

Pandemic stress could be biologically imprinted in children

Stressors stemming from the pandemic such as the above could become biologically imprinted in children and leave a lasting mark on child and adult health and well-being, Michael S. Kobor from the Department of Medical Genetics at the University of British Columbia told The Conversation. “There are several biological pathways that can be modulated by early life experiences, but epigenetics — a process that turns genes “on” or “off” — is particularly well-studied. Epigenetic changes associated with early experiences can last into adulthood and may be linked to stress, inflammation and chronic heath conditions.”

Because children’s growing bodies are still laying the foundation blocks of their physical health and their emotional and psychosocial artillery, any major events that happen while they are in this vulnerable phase could have lifelong consequences. “While scientists continue to map the exact mechanisms by which early experiences impact adult health, what is clear is that children who experience adversity early in life are at heightened risk for later mental, social and physical health problems,” says Kobor.

What parents have noticed

Monisha Gumber, 43, told Gulf News that her 18-year-old daughter has been more affected by the COVID-19-related restrictions than her 12-year-old son.

“Older kids read and hear more about what is going on, and are therefore more vulnerable to suffering from anxiety and stress. Often burdened by exam stress, they can no longer socialise and unwind. In contrast, younger children have often found themselves in their own world,” Gumber says.

Her daughter has suffered for being unable to go out with her friends every week, either at malls or at her friend’s houses.

“It didn’t help that she is facing the IB soon. Only over the last month or so, she has met her friends a few times, but certainly much less than before the pandemic. My son did not feel it much, especially because he has always been homeschooled. He instead enjoys wearing different face masks,” she says.

Gumber adds that she knows of several children who have begun seeing counsellors to deal with the stress, anxiety and social isolation brought about by the pandemic.

Robyn Chislett, a South African homemaker and fine artist, says that she too worries about the impact of COVID-19 on her 14-year-old twins.

“Teens thrive on social interaction, praise and feedback, so the restrictions were hard for my girls. They were less cheerful, and couldn’t wait to go back to school. I felt that they became a lot more insular, and increased their screen time dramatically,” she said.

For the last month or so, the twin girls – Jemma and Erin – have been finally able to attend school two times a week, and Chislett said they are very excited about this.

“I am concerned that this forced segregation will have an impact on their wellbeing. But I also realise that children are very resilient, and find their way through things. For instance, my girls started keeping in touch with many of their friends over Zoom, including those who live outside the UAE. So it’s as if they have forged their own path. In fact, I feel that we struggle more as adults,” she added.

Natalee Busteed, a Dubai-based fitness trainer from Australia and mother of four (aged 11, 15 and 18-year-old twins) says that her children have all been impacted differently by the pandemic too.

“My youngest, 11, did not get to graduate from primary school or transition gently to high school. He didn’t get to have his prom either. He was acutely aware of the pandemic and the number of cases and certainly demonstrated anxiety during the first few months.

“My daughter, 15, also found this time particularly difficult and has been quite anxious. She struggled with the online education, lack of socialization and sport. She doesn’t cope well with change and still finds it hard to adjust to the new normal. As she is in GCSE years I do have concerns about her education.”

Natalee’s 18-year-old twin boys, by contrast, seem to have fared better. “They have been lucky in the sense that they have not missed any key milestones yet,” says Busteed. “They were in the final term of year 12 when it all began. They have handled the situation well and adapted to online school. However, I am concerned about their A-Levels and whether they have covered enough content. I am also concerned about the implications it will have on scoring and entry to university.”

What teachers say

Anna White, student support counsellor at Hartland International School in Dubai says that, although students from year 1 to year 11 have all been delighted to be back at school in person, as time has gone on, some have become frustrated at not being able to play with or connect as freely with their friends - both within and without classes. “I have found this to be more distressing for students the further up the school they are, although this does depend upon how classes are structured, and which friends are in their bubble.”

She says that in most cases, the status quo has remained; “meaning that those students with a positive outlook and disposition have stayed resilient but those prone to emotional instability have struggled and possibly worsened due to the changes and subsequent new normal.”

The relatively new phenomenon of students playing with each other via on-line games cannot be under-estimated, adds White. “I believe this is one of the biggest changes and could well be long-lasting. Before Covid-19 came about, upper primary school children in particular, could be seen playing together after school, usually outside, whether riding their bikes, kicking a ball or running around. I know now of whole classes who will go home from school, only to join up again immediately upon returning, into their virtual worlds.”

So how does this impact a child or teen? “I believe that, for the most part, this sense of social connection is as good as, if not better than before,” says White. “Children certainly seem to be connected for longer. We know that healthy social relationships are vital for wellbeing, and even though much is now virtual, most students have adapted to this with ease.”

However Hartland’s White also points out the lack of physical activity that has come along with this extra screen time. “I am not sure this will fully change until Covid goes away – and in some cases, these new habits may never revert. Children and teens can still stay physically fit, however I am persuaded that there needs to be a much more intentional and determined approach, as the new normal does not allow for as much natural movement.”

Meanwhile Sara Hedger, Head of Safeguarding & Child Protection at GEMS Education, says that those children who have missed major life milestones may be suffering for it, especially older kids and teens who have missed out on proms or graduations: “The older students leaving for university have also been affected, not only with the reorganisation at very short notice of external exams but once at university, many have been quarantined and have virtual classes for the first year. This can be very hard on the mental health of young people and inhibits the traditional and very important social side of university life.”

For the youngest students, who have had a significant amount of their time at home with parents and caregivers, socialisation has needed to be much more intentional than it would be in a normal year. “Integrating them back into school or attending school for the first time has meant that many of the basic social and emotional skills that students traditionally develop within and outside of the home environment (such as nursery or on play dates) has had to be explicitly worked upon. Sharing with others, managing conflict and establishing or maintaining friendships over and above just being with other students, when you have been used to being on your own are all skills that need to be learned and refreshed.”

The advent of COVID-19 has caused every parent to travail through unchartered territories this year. And as the pandemic rages on across the globe, I wonder often about its long-term repercussions on my children.

They’re both still very young: my eldest was only in his first year of formal schooling when the pandemic shuttered the UAE’s physical classrooms for the first time in March. My daughter, on the other hand, turned two this summer in a small family celebration that we were too wary to take out of the house.

At the outset, understanding little about this whole new world – just like the rest of us – the children were actually happy to see more of us, even as my husband and I spent more hours at work on our laptops. And for weeks, they didn’t really understand why we did not venture out of doors; after all, their sense of time had not really been broken down into weekdays and weekends yet.

CORONAVIRUS TALK

The ‘coronavirus talk’ eventually rolled around when my son finally asked to visit his school library, sometime during the third week of remote learning. We discussed it briefly. But without much opportunity to go out, we carried on with Ramadan and the summer, choosing to dwell on the blessings of being home with the family rather than the freedoms stripped from us by a microscopic organism.

It was when the coronavirus outbreak did not abate enough by the end of the summer that I could not help worrying about how this phase would impact their lives.

NO SOCIAL TRAINING

My son has generally taken a bit longer to adapt to new settings and people, and we had always hoped that school would help him shed some of his shyness. He is still attending classes from home, so there really hasn’t been much of an opportunity for that kind of social training yet. When this pandemic has passed and he finally gets to go to school regularly, will the social experiences prove too overwhelming?

I also notice, quite clearly, how my daughter – who is otherwise very assured and articulate – refuses to let go of my hand when we venture outside. She is hesitant and worried, appearing quite unlike the feisty, little girl who knows her mind at home. Unlike her brother, she is not cognizant of the joy of visiting a park or play area every weekend, and has no memories of enjoying dinner at the mall. It is also clear that she doesn’t yet recognise Abu Dhabi’s landmarks, simply because we go out so rarely that she has not yet had a chance to see them over and over.

FACE MASKS: NEW NORMAL

I’ve also noticed how the children have adapted quite easily to wearing masks. In fact, they regularly remind their father, mother and grandparents to don the piece of PPE when we are stepping outside the house for work. My son has quietly incorporated face masks on all his Lego figurines, as if it is just that simple. It makes me think: will they one day be scared to go out without face masks, if and when it is safe to do so? Or will they become more comfortable with a world where smiles remain hidden behind a piece of cloth or plastic?

When I dive into that wormhole of worry, it can be hard to extract myself, especially because I am fully aware that my children are still in their formative years, when every action and memory leaves an imprint on the future.

NURTURING RESILIENCE

Then again, I know that the kids are still very young, and therefore more naturally resilient than I give them credit. They’ve been able to adopt stuffy face masks into their daily apparel with far less pushback than adults; they’ll be able to figure out social mores in the classroom just as easily, I assure myself.

I also do take heart from my daughter’s sense of appreciation for the littlest things. My son, being older, still misses his trips to amusement parks and arcade, and a simple walk doesn’t always bring him a lot of delight. But his little sister is forever squealing with joy, making the most elated overtures to the simplest outing.

So maybe there’s hope just yet. Perhaps they’ll actually be able to come out of this pandemic with heaps of gratitude, kindness and grace for this crazy world.

Psychologists: Age matters when it comes to the impact of the pandemic

As parents have noticed, the fall-out of COVID will have a different impact on children, depending on their age, stage and personalities, says Dr Saliha Afridi, clinical psychologist and director of The LightHouse Arabia.

For littler kids, their limited understanding will affect how they process the situation. “Because children do not have the cognitive abilities to fully comprehend what is happening in the world, and young children are egocentric, they can often feel that such events are either their fault or somehow if they behaved better, that they would be able to go back to the way things were (ie. go play with their friends the way they used to).

“Children are also very tactile and need a lot of physical reassurance from teachers and their friends—they will not understand why their teacher can’t hug them the way they used to, and instead they might internalize such moments as something being wrong with them.”

Children are forming models of social interaction that can stay with them for life, so the social distancing may matter even more for kids than for adults. “Childhood is a time of great social and emotional development and much of that happens in play and on the playground,” adds Dr Afridi. “The school and play environments have become sterile and ‘socially distanced’ and this leaves a child missing out on some important elements of social and emotional development.”

However, the hardest aspect of COVID for younger children is the impact it can have on their parents, says Dr Afridi. “If a parent is feeling stressed, overwhelmed or anxious due to world events, then it is likely that they will not be able to see, contain or help their child process the difficult emotions that the child might be going through. Children look to the parents to regulate themselves and if the parent’s nervous system is overloaded, then it is likely that they are unable to be fully present for their child.”

Maryam Ehsani, founder and CEO of Child Safe ME agrees, adding that we can all take a small step towards making things better by first taking care of ourselves. “We need to start walking the talk. We all have to be aware of our mental health conditions and find new ways of managing the new reality. One thing that connects all of us is that we are not alone in this and the entire world is going through the same crisis. We just have to make sure we stay on track with our own emotions as parents.”

Early Childhood (0-5y)

this developmental stage is more sensitive to trauma and this latest may have long-term consequences across their lifespan. So any complications that might hit the family on any level, socially, financially, or health, it will affect the children and they will carry its residue to their adult-life.

Childhood (6-12y)

Children this age, are extremely interested in socialization. Missing social significant event will affect these children negatively. Social distance in this period of age is hard to be understood and processed by children.

Adolescence (13-18 years)

As for the adolescent, they are more affected by their prolonged exposure to online activity and this can increase online harm such as sexual exploitation, cyberbullying, online risk-taking behavior, and exposure to potentially harmful content

Older children may have it hardest

Everyone has been impacted by COVID, but those who are most affected by it are teens and college-aged young adults, says Dr Afridi. “This is a time when the child breaks away from the parents and joins a social group and experiments with many different identities. This is not a time a child wants to be locked up with his/her parents. It is also a time when they are learning a lot about relationships and how to navigate those relationships—and most of that is learned through casual interactions in the mall or at parties, or in lecture halls.”

The milestones that UAE parents note their children have missed out on do matter, adds Dr Afridi. “These years are also filled with important moments such as a child’s first dance, their first date or graduation, or having the college experience. For these kids, they will never be able to get these chances again, and this is why it is the hardest for this particular age group. There is a lot of loss and grief associated with losing such important moments.”

It is important to validate and grieve the losses, she says. “It is a difficult time for teens and young adults, but having a supportive adult who is a compassionate witness through their grief can help them overcome such difficulties, and even grow stronger as a result.”

How parents can help children

The lasting legacy of COVID on children is hard to predict for certain, says Dr Paul Gelston, clinical psychologist at Dubai Community Health Centre. “We have a choice to make about how it impacts people,” he says. “There are of course potential negative impacts – increased discussions about germs, handwashing, masks and so on can possibly create higher levels of germ anxiety in kids and teens for example. But parents and caregivers can be children’s safety net and shape how they adapt and cope with these changes going forward.”

Dr Gelston says that one of the silver linings of the pandemic has been that many more people are now talking about its impact on mental health, which has woken many of us up to the things we need to most to support our emotional wellbeing - something he says was sorely needed. “I would facilitate the mental health and wellbeing conversation as much as possible to normalise the experience of the child you are supporting. I would also intentionally carve out blocks of time for specific activities, making it clear what and why you are doing something. This means ensuring you have work/life balance, that you have dedicated family time, spend time outside – the sort of stuff you’d do anyway but might not explicitly label.”

But if you notice any ongoing behaviour that is out of character for your child, then it may be time to seek professional help, says Dr Gelston. “You know your child best and what is typical for them, but if a child is acting uncharacteristically withdrawn, anxious, asking many more questions than usual or are afraid to be apart from you then it may be a potential warning sign.”

“I think there will be children who thrived during this period, and others who really struggled,” predicts Dr Saliha Afridi from The LightHouse Arabia. “Even before COVID, one in five children and adolescents were struggling with mental health difficulties—and depression was the leading cause of death worldwide for adults. COVID has definitely exacerbated the situation and made things more difficult for children and families.”

But there’s plenty parents can do to help, she adds. “I think it’s important to know that children are resilient and they will overcome, as long as they parents prioritize their psychological and physical health above academic development. For resiliency they are going to need rest, routine, and healthy role modelling.”

1. Be trained in Mental Health First Aid- if we know that the rates of mental health disorders is on the rise and children and adolescent are more vulnerable then as a parent you should be trained in MHFA, so you feel empowered to be able to detect the signs and symptoms of major mental illness and their symptoms and act accordingly. This is no longer a nice to have, but a must have for parents of preteen/teen and young adults.

2. Invest time and energy with children – parents will be the anchor of their children in times of storm. Children need positive role models in the form of parents and other close attachments. They may need a bit more of your love, interest, attention, and validation. This means you have to fill your own cup so that you can pour into theirs without feeling burnout.

3. Let go of the perfectionism. When it comes to expectations you have of yourself or your children, make a list of things that are uncompromisable—and then loosen up on everything else. Uncompromisable things should include routine, daily exercise, sleep/waking up time, how often you allow junk food, and asks you have each other that are related to your family values.

4. Relax the technology rules but still limit the entertainment technology and only allow for educational technology to be used by children. This will help buy you some time to get your work done, while they are engaged with something else.

5. Spend time in nature: As much as possible try to get outside your house and into nature. Go for walks, to the beach, to the dunes—but put the phone away and really enjoy the earthing energy of nature.

6. Have some rituals and traditions during COVID. This could be that every Wednesday you have movie night and every Friday, you have game night. These traditions and rituals ground children in the week and give them something to look forward to.

7. Validate their emotions. This is not easy for anyone, but parents who are saying “you think it’s hard for you, look how hard it is for me” do not help children feel seen or heard. By saying “this is hard for you” or “tell me what you miss most” you create safety for your children to share their experience and to be seen. This is critical for resilience: to have one adult who sees and hears you.

8. Stay active: This can be something you do as a family but it is important for anxiety and depression management to stay active and not succumb to hours of Netflix, gaming, or social media.

9. Guard your sleep and theirs. There is not a single mental health problem that doesn’t have sleep component to it. This means you get blue light blocking glasses/screen shields, avoid technology close to bed (especially for teens), and engage in other pre-bed routines to get a good night rest.

10. Take care of your own mental health- as parents you are the anchor and the guiding light for your children. If you are unwell, seek support from a professional so that you can give your family what they need.