Just as I was blissfully settling into my first year of motherhood, life threw a curveball at me when my daughter was diagnosed with life-threatening food allergies.

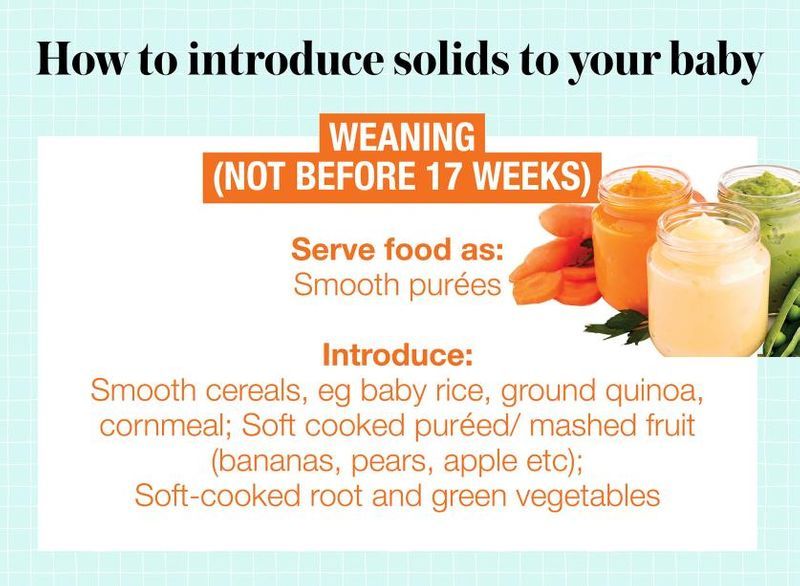

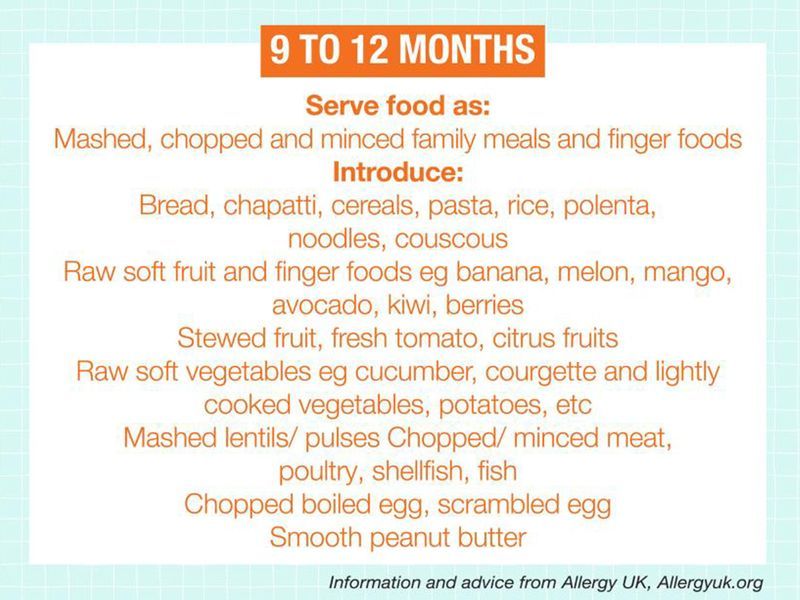

At that time, I was enjoying the weaning stage of her babyhood, gradually introducing her to the recommended new foods: rice cereal, fruits and vegetables. However, after a few weeks of persistent atopic dermatitis – or eczema – my then eight-month-old daughter’s paediatrician suggested we do a test for food allergies.

We were in disbelief when the results arrived. They revealed a list of allergenic foods that could be potentially deadly for our little girl: peanuts, tree nuts, eggs, fish, shellfish, soy and sesame. These were all foods that she had not yet tried.

As someone who had absolutely no familiarity with the concept of food allergy, I was shocked. Where had she got this life-threatening condition from? Was there something we could have done to avoid it?

My daughter was prescribed an epinephrine auto-injector – or an epipen – as the primary treatment for anaphylaxis, and we were sent home with instructions to strictly avoid contact with any allergens, plus reams of reading material to educate ourselves about food allergies. The serious reality of her diagnosis began to sink in…

Managing food allergies

Allergies arise from an immune response to a substance (allergen) that the body doesn’t recognize. We were told by my daughter's doctors that possible allergic reactions could range from mild (like coughing or sneezing) to life-threatening anaphylaxis, which requires emergency treatment.

Anaphylaxis can lead to anaphylactic shock, which is characterised by symptoms like wheezing, dizziness and vomiting. The pulse can slow, blood pressure can drop, and the airways can close. For some people, it can be fatal.

As stressful and worrying as all of this was, it was manageable at first. Since my daughter was still an infant and being cared for at home, we were in complete control as her primary caregivers, and we would take extreme care to ensure that there was no cross-contamination with any of the allergens during the preparation and feeding process.

But there were still unexpected scares along the way. At the age of 18 months, we found out that she was severely allergic to lentils as well, after a serious reaction that made us frantically rush to the hospital.

It was as she grew older that living with a food allergy started impacting our lives even more. It required a whole new level of planning, including sharing our food-safety protocols with family and friends - especially when it came to travelling, eating out, and social activities.

Celebrations often revolve around potentially allergenic desserts, so we always had to have a stash of allergy-free treats to hand in order to stop her from feeling left out if we couldn’t let her partake. Travelling to places where English was not widely spoken and communication about safe (and hidden) ingredients in restaurants was often exasperating. Grocery shopping for pre-packaged foods was never quite the same again either, requiring vigilant reading (and re-reading!) of ingredient labels and the manufacturer’s processing details.

Then my daughter’s schooling began. This triggered a new height of anxiety for me as she was out of my care for much of the day. How vigilant was the school about food allergy? Were the teachers trained to use epipens? How far was the closest hospital, in case of an emergency? I made her wear a medical alert bracelet, and allergy action plans were shared with school staff. And then, of course, there was the importance of educating my own young child that she could only eat her own food and not ‘share’ anything that a friend might be eating – something that all children have had to become used to at school during COVID, but which takes on a whole new level of seriousness when anaphylaxis could be the potential consequence.

Now in her teens, my daughter’s allergy testing has been carried out annually. While she thankfully grew out of a few allergies by the age of eight, the ones remaining will likely continue to be severe and life-long.

Food allergy on the rise

As a parent of a child with life-threatening allergies, there have been many times when I have felt incredibly alone in a crowd of people unaccustomed to food allergy, but the fact is that they are on the rise and fast becoming a serious global health concern.

The rate of food allergies worldwide has increased from around 3% of the population in 1960 to around 7% in 2018, Kari Nadeau, a Stanford University allergy specialist and author of book ‘The End of Food Allergy’ told the BBC.

The range of foods that people are allergic to has also widened - from the key allergens seafood, nuts and milk, to a whole range of different foods. Meanwhile more people are being admitted to hospital for anaphylaxis around the world, with April 2021 research from the Natasha Allergy Research Foundation showing a 200% rise in acute anaphylaxis happening in children under the age of 10 in the UK. As stories about food allergy spread across the globe, a gradual awareness is starting to emerge, although there is still a lot that is uncertain about this immune-based disease.

Why food allergies are increasing

There have been numerous theories to explain the increased prevalence of food allergy. According to Dr Carlos Baptista, paediatric specialist at Novomed, "one of the theories explaining this increased prevalence is the changed intestinal microbiota associated with the excessive use of antibiotics and increased Caesarean births," he says. Profiling of the gut microbiome in human studies has demonstrated that individuals with food allergy have distinct gut microbiomes compared to healthy control subjects, and an imbalance in the gut bacteria has been shown to precede the development of food allergy.

"Other theories could be related to lower rates of breastfeeding, lower exposure to dirt in early childhood and higher exposure to processed foods (containing many food additives and drugs for animal use); all these situations could favour the emergence of food allergy, particularly in genetically predisposed children. The improvement of diagnostic methods, the understanding of food allergy and the spread of information have also contributed to this perceived increase in recent times.”

The controversial hygiene hypothesis another theory, says Dr Baptista. The idea is that "improving hygiene can be one of the causes, since children are not having as many infections. Parasitic infections, in particular, are usually counteracted by the same mechanisms involved in combatting allergies. With fewer parasites to fight, the immune system turns against elements that should be harmless."

Dr Baptista also adds that "a theory of ‘dual allergen exposure’ suggests that the development of food allergy is due to the balance between timing, dose and form of exposure.” The idea is that being exposed to allergens through the skin can lead to allergy, while being exposed to them through eating can potentially result in tolerance. Depending on to what extent children are exposed to the allergens, and through which route, either tolerance or allergy can ‘win out’. For example, kids who have eczema have a disrupted skin barrier, through which allergens in the environment are able to enter – whether it’s in the form of nut oil in a body cream, or peanut residue on a table. According to the ‘dual allergen exposure’ theory, if these children avoid eating nuts but are still exposed to them in the environment, they might be more likely to develop nut allergy.

Real vs false allergies

"There’s no question that there has been much more food allergy in the past 20 years," says Dr Michael Loubser, specialist paediatrician, clinical immunologist and allergist at Genesis Healthcare Center. "What’s increased for sure is real food allergy. Unfortunately, along with real food allergy skyrocketing, so too has the false perception of allergy and the adverse events associated with it. About 25% of people think they have a food allergy, but in adults it’s actually less than 1% and in children it’s about 3-5%."

Since food allergy diagnosis is bound to have an adverse impact on the quality of one’s life, Dr Loubser – who helped develop Canadian guidelines for managing life-threatening food allergies – stresses the importance of correct diagnosis, as non-allergic food reactions and intolerances that don’t involve the immune system can often be misinterpreted as food allergies.

Who is most likely to get a food allergy?

Dr Loubser explains that there are two components to developing food allergy – one is genetic and the other is exposure. "In the main, you have a genetic predisposition to developing allergy and how you manifest your allergies can vary," he explains. "You might have a genetic predisposition but you might get eczema, you might develop asthma and some people develop food allergy. But there are also people who don’t have much in the way of an allergic history who get allergic to food.

"Your immune system is designed to be tolerant to yourself and to pretty well kill everything else, because its job is to stop invading microorganisms. If you are exposed to a food very early on and if you are exposed to it a lot, your immune system tends to see it and go, ‘I’m seeing a lot of that – it’s no risk to me – I’m going to leave it alone.’ However, if you introduce food late, or if you have an intermittent exposure, your immune system starts to get suspicious of that and that’s the risk."

New advice on allergies for parents

The traditional medical advice for new parents was to avoid common food allergens, such as peanuts, eggs, tree nuts and fish, for the first few years of their baby’s life.

But in 2008 the American Academy of Pediatrics reversed these guidelines, noting that there was no evidence that the avoidance was working to prevent food allergies.

According to Dr Loubser, recent studies suggest that this advice to avoid exposure to allergens actually contributed to the increase in food allergies, and that early exposure to allergens may potentially prevent food allergy. "Almost certainly part of this epidemic of food allergy was created by us telling people to avoid foods," he explains."Because now the guidelines are very clear – that you can reduce food allergy by up to ten-fold by early introduction of foods."

He refers to the LEAP trial – a clinical study investigating how to best prevent peanut allergy – which shows a massive reduction with early intervention. The trial showed that the kids who had peanuts introduced early had a much lower incidence of being peanut allergic compared to the group that had avoided peanuts. "We’re talking introduction of peanut at age four months for example, which is the design of the LEAP trial," says Dr Loubser. "So what might have happened when we say no nuts and other allergenic foods until a certain age, is that we may have actually precipitated this issue. All of the very important allergens were being withheld, which was perhaps wrong."

- As a result, a number of chemicals are released. It's these chemicals that cause the symptoms of an allergic reaction.

- Almost any food can cause an allergic reaction, but there are certain foods that are responsible for most food allergies.

- Most children that have a food allergy will have experienced eczema during infancy. - The worse the child's eczema and the earlier it started, the more likely they are to have a food allergy.

- It's still unknown why people develop allergies to food, although they often have other allergic conditions, such as asthma, hay fever and eczema.

Source: NHS

Signs of a food allergy

What should parents look for if they suspect their child might have a food allergy? "Your first clue in most babies is eczema, and then obviously it is the immediate reaction to the food," explains Dr Loubser. "The important thing about food allergy is the timing: 15 to 40 minutes roughly is the average time that it takes somebody to react after ingestion of a food. If you’re getting a reaction that happens the next day, it isn’t food allergy. Even if you’re getting a reaction that happens six or eight hours later, it probably isn’t a pure food allergy. The manifestation in babies would typically be immediate rash and gastrointestinal – they would typically vomit. Babies seldom present with major respiratory problems for their first time. The other thing about food allergy is that it’s repeatable. It isn’t dose dependent. It’s very consistent, it’s very immediate and it mainly involves skin and gut in babies."

Can kids grow out of their allergies?

Is there a cure for food allergies? Dr Baptista explains, "So far, there is no treatment that can cure food allergies, but rather control the symptoms. Immunotherapy with allergens – administration of small amounts of the substance – has been shown to reduce the sensitivity of allergic patients and may protect against accidental exposure. But this is not completely safe, has many side effects and the protocols are circumscribed to only some centres."

However, the good news is that children can typically outgrow some food allergies, although it might not always be the case. "Most forms of food allergy (such as milk and eggs) that affect children are transient, and the mechanism of tolerance to allergenic protein is established even in the first years of life", says Dr Baptista. "An exception is allergies to peanut protein, nuts and seafood, which are usually persistent. Thus, it is important to establish the correct diagnosis of food allergy and adequate diet, allowing the child to grow and develop until they are tolerant and stop being a carrier of food allergy."

How to reduce the risk of your baby being allergic?

Is there anything we can do during pregnancy and infancy in order to reduce the risk of our children having allergies? "The first advice is that you can’t do tests to predict if your child is allergic – we can’t predict who will have an allergic reaction or not," says Dr Loubser. "You can’t use testing as a crystal ball. The earlier you introduce solids, the safer it’s going to be. The guidelines will say that the higher at risk you are, the earlier you introduce, which would generally be around four months of age. If there is a reaction, you need to see an allergist to make a diagnosis. We know that we encourage breastfeeding, and we know that we now encourage early introduction of solids. We ask mothers to eat a broad-based diet, but to the best of our knowledge, there isn’t any ‘primary prevention’ for food allergy yet."