KIDS' COVID CURVES: HOW TO HELP?

- Children have piled on the pounds during the pandemic

- Excess weight in childhood is linked to many diseases as well as negative mental health

- But body image is a sensitive topic and needs to be dealt with delicately by parents

- How can parents help an overweight child without making it worse?

Nadine Sabbah’s 10-year-old daughter always loved being physically active. Pre-pandemic she did four hours of gymnastics per week, and like most kids her age she’d spend hours running around with friends in her community. But then COVID-19 hit. Her gym classes were cancelled, and she went from having regular exercise to staying home all day.

With news of the virus so rife and uncertain at the beginning of the pandemic, the little girl even became afraid just to go for a walk outside in her local area.

But it was when mum Nadine noticed her daughter becoming self-conscious about her body that she started to worry. “She started to gain a bit of weight and it really affected her behaviour,” says the Lebanese/ French expat, who also has a 6-year-old daughter. “She started becoming anxious, and we noticed she would wear only loose-fitting clothes to hide her body.”

The pandemic pounds

Nadine is far from alone in being concerned about her child’s weight over the pandemic. As lockdown made our worlds shrink smaller – closing down schools, gyms and travel options – we all grew larger, according to research published in JAMA Network Open.

People put on an average of 1.8 pounds per month during shelter-in-place orders in the US, according to a March 2021 study of 7,500 people. And, although data is sparse with regards to weight gain in children at the moment, experts believe the same trend can be noted in the paediatric population in the developed world.

“We can most certainly assume that there has been an increased number of children gaining weight during the pandemic,” says Jordana Smith, dietician at Genesis Clinic in Dubai Healthcare City. “In my own practice, I most certainly have seen an increase in the number of overweight children and parents concerned about their child’s weight.”

Why have children gained weight?

With group sporting activities and classes cancelled or curtailed, as well as extra caution with regards to going out at all, children’s physical activity levels have plummeted, while screen time and access to sugary snacks has soared.

“Children and teens are going to bed later and getting up later disrupting their ‘normal’ schedules,” says Dr Nancy Ahmed Radian Ghanem, Specialist Paediatrics at Prime Medical Center in Dubai.

“The impact of late nights is compounded daily and affects other aspects of children's lives – such as meals, nutrition and physical activity.”

Online schooling eliminates the opportunity for children to walk to their classes, participate in PE lessons, or run around during recess, all of which provide great exercise that we wouldn’t really notice in a normal day, says Dr Nancy: “Add to that the stress of living in a time of uncertainty, and children may react by reaching for sugary and fatty snacks, leading to unhealthy eating habits that can contribute to weight gain and jeopardize their long-term health,” she adds.

During a time when so many things have felt out of control, food is the one area in which children and adults alike have been able to exert some form of autonomy, says Nadia Brooker, Counselling Psychologist at Priory Wellbeing Centre Dubai – who has also witnessed a rise in the eating disorder anorexia amongst her patients. “The current COVID-19 pandemic is having a significant impact on all of our daily lives – young and old,” says Brooker.

“There is so much uncertainty and change happening right now that it can be really hard to keep track and manage our physical and emotional wellbeing.

We are all experiencing numerous, difficult emotions such as stress, sadness, fear, boredom and loneliness, all of which can often lead to changes in appetite that can eventually lead to disordered eating patterns, such as over-eating.

For children and young people in particular the increase in their screen time goes hand-in-hand with sedentary behavior, and so this lack of physical exercise also facilitates weight gain.”

What is the difference between normal and abnormal weight gain in kids?

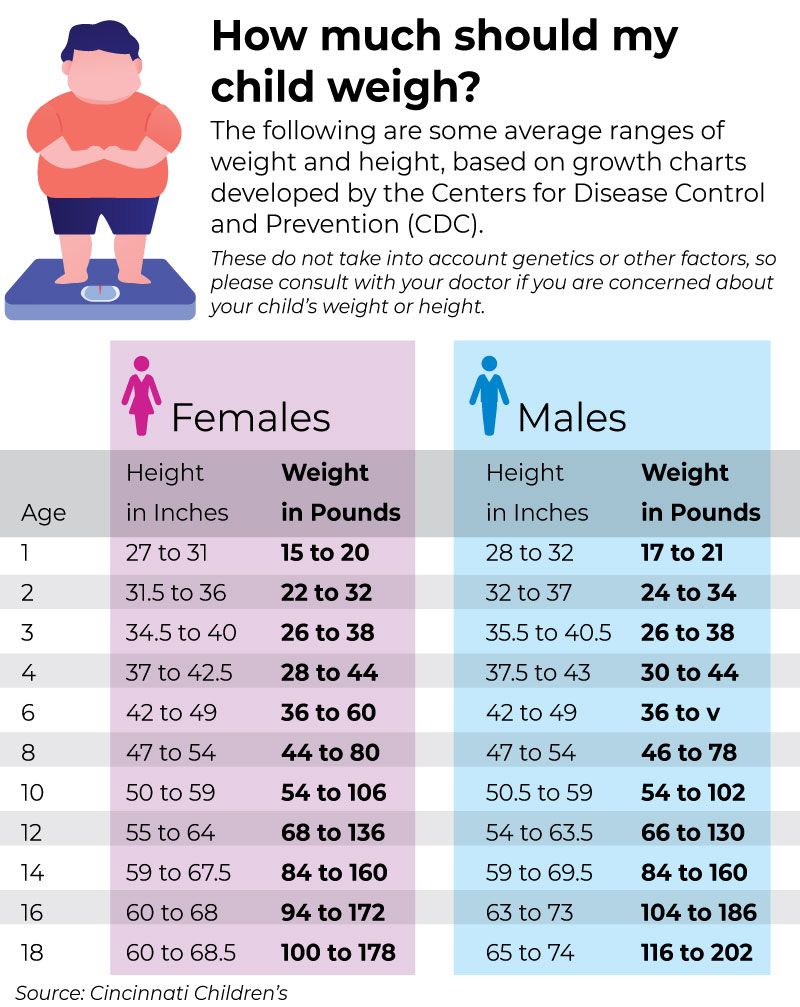

Unlike adults, children are supposed to gain weight steadily as they grow. But when does childhood weight gain slide from healthy into unhealthy? “Normal weight gain varies depending on the age of the child, but the range would be anywhere between 1.8 - 3kg per year in weight, and 5 - 7cm in height until the child reaches puberty,” says Dietician at Genesis Clinic Jordana Smith.

During puberty the childhood growth rate doubles, explains Prime Medical Center’s Dr Nancy, “but because some kids start developing as early as age 8 and some not until age 14, it can be normal for two kids who are the same gender, height, and age to have very different weight.”

She says children gain on average between 13.5-18kg between ages 11 and 14. “A child can gain 9kg or more in one year during this age range.”

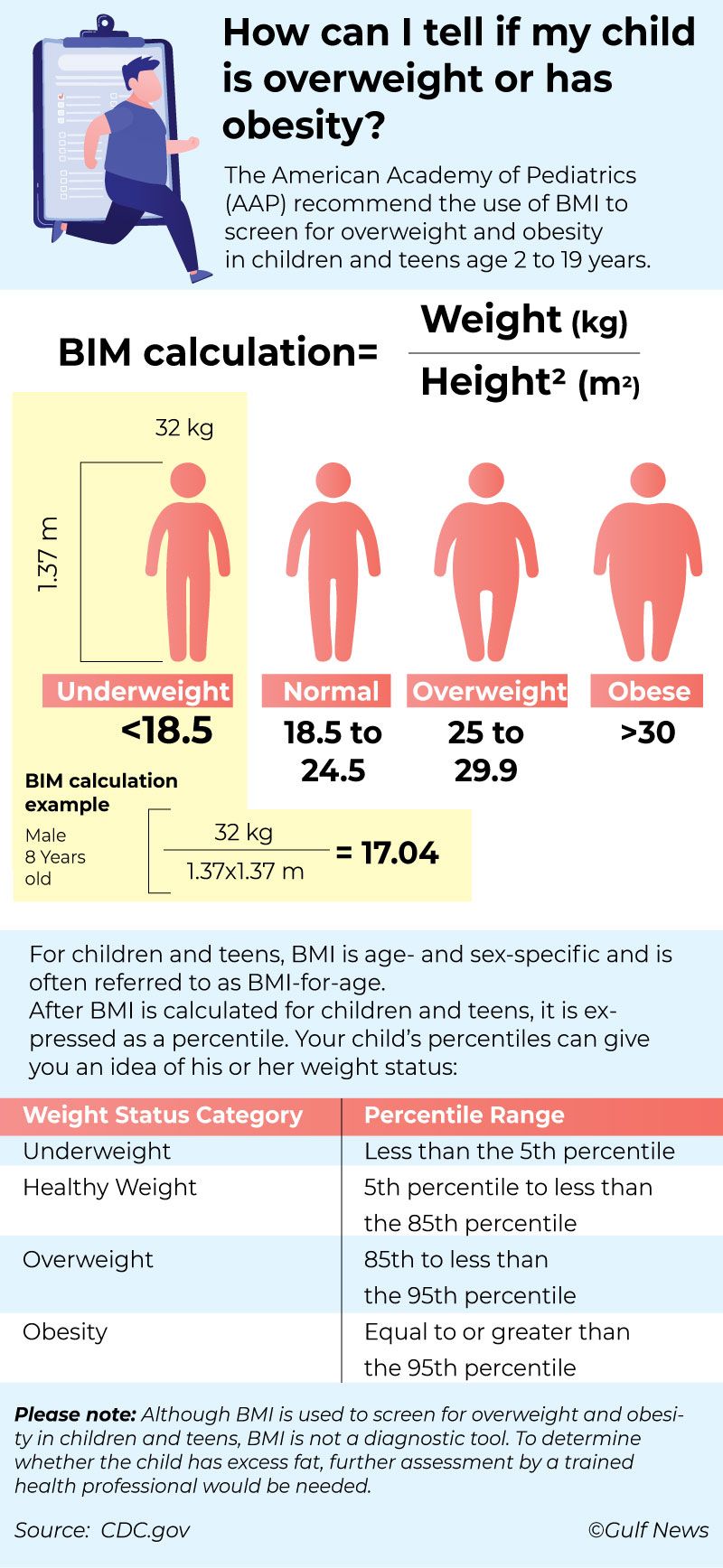

With children, we look at both their ‘percentile’ – which is the percentage where your child falls in height and weight in relation to other children – as well as their BMI (Body Mass Index). “We need to have 3% of babies and children falling on the 3rd and 97th centiles, as this is normal population standards,” explains Jordana Smith. “Not all of us look the same; we have small or short people and we have taller people - this is where genetics starts to come into play.”

But we cannot determine if a child is overweight or underweight just by looking at their centiles. “We would need to look at their curve (at least 3 points), and then also compare their weight-to-height charts (or BMI charts) to see where fall on those,” says Jordana, pointing out that we also need to remember that BMI ranges are different for children than they are for adults.

When should a parent worry about their child’s weight?

A little bit of rapid weight gain here and there isn’t a worry in children necessarily – it can be normal for them to get larger for a while before shooting up in height son afterwards. But Jordana Smith says a parent should become concerned about a child’s weight (under or over), when there is a cross over or levelling out of centiles on their growth charts. “This needs to be a pattern for three consecutive measurements. It is not only about one point taken, we need to be looking at the pattern and also be considering genetics of the family.

“If you child is beyond the 100th centile, I wouldn't automatically go into panic mode, but I would start investigating their full growth chart history and definitely be looking at genetics and what their height measurements are.”

As a general rule a BMI of 95 or above indicates obesity, says Dr Nancy, while percentiles between 85 and 95 indicate a child is overweight, “so parents should be aware of that by closely monitoring their kids for any sudden weight gain that can indicate any underlying problems, or even gradually abnormal weight gain that can lead to obesity.”

“It all comes back to looking at their charts and seeing how they have been growing over time. I will also consider if a child was breastfed or given formula milk. We generally expect breastfed babies to be smaller due to the composition of breastmilk, than formula fed babies who we expect to be bigger due to the higher protein content in formula milk.

"’Puppy fat’ is the fat the children have when they are younger but starts to disappear as child moves into adolescence and starts to get taller. Typically I am not too concerned about a bit of puppy fat - I would still educate the entire family about better food choices and movement.

“If there are rolls on the arms, legs and back then that may start to ring some alarm bells, but if it is centered in the mid area and on the face I wouldn't be too concerned.”

How much does being overweight matter for children?

Being overweight or obese in childhood are well known to have a significant impact on both physical and psychological health. Children are more likely to stay obese into adulthood, and to contract diseases like diabetes, cardiovascular disease and asthma. The emotional impact of being overweight is also well-documented, with children more likely to be teased or bullied for their shape, which can lead to anxiety and depression.

“Many parents consider a heavy child as having baby fat and reassure themselves in thinking that their overweight or obese child will simply outgrow it, but the reality is quite the opposite,” says Dr Nancy. “In a 2014 study published in the ‘New England Journal of Medicine’, researchers evaluated changes in the rates of obesity in more than 7,000 children between the time they entered kindergarten and advanced to middle school age. The results showed that being obese during kindergarten increased the likelihood of being obese during middle school.”

Dr Nancy also points out that being obese increases a child’s risk if they do contract coronavirus: “The virus can affect children’s breathing, immune system, metabolism and cause inflammation. Those with obesity also can develop high blood pressure, liver problems or diabetes. Having these health issues puts them at high risk if they get COVID-19.”

How should parents react to an overweight child?

Parents who are concerned about addressing their children's weight must tread carefully. Weight and body image are incredibly sensitive topics, and those who stumble into the conversation unprepared can inadvertently exacerbate the various stigmas around eating disorders and obesity, which can have their own very serious consequences for a child’s health.

“Personally the way I approach it in my practice, is to never single the child out for being over or underweight,” says Jordana Smith. “Rather I would focus on the overall health of the entire family, because more often than not the whole family actually needs to make some changes and not only the child.”

Parents should discuss weight and health issues in a supportive manner, not in a manner of control, to enable them to feel safe to discuss any issues they may be experiencing as well

“I never suggest weight loss in a child, what I then prefer to focus on is for the child to grow into their weight, so we would be looking for weight stabilization for a period of time. The focus is always going to be on education, in terms of food choices, physical activity and I spend a fair amount of time on mindful eating.”

It's important to role model a healthy body image as well as health habits, agrees Dr Nancy.

“Judging your own body or your child's can result in lasting detrimental effects to your child's body image and relationship with food. Set a good example for children in the way you talk about your own body as well as others,” she says.

“Children learn fast, and they learn best by example. Teach children habits that will help keep them healthy for life.”

There is no point in sitting a young child down and lecturing them about the dangers of obesity, says Dr Nancy. “In general, if your child is elementary age or younger and you have some weight concerns, don't talk about it; just start making lifestyle changes as a family. The best thing you can do is make it easy for kids to eat smart and move often. Serve regular, balanced family meals and snacks. Limit the time your child spends watching television or playing video games. Look for ways to spend fun, active time together.”

Should you put your child on a diet?

All of the experts agree that putting children on a diet is a big no-no.

I think it would be a big mistake to think about putting kids on diets or counting calories during the major stress of a pandemic.

“And research shows that childhood dieting can increase the risk of eating disorders later on. So, parents should keep their child’s overall health, including mental health and growth history, in perspective.”

“I would never put a child on a diet,” agrees Jordana. “We don't want any calorie restriction but certainly by making better food choices we do notice a change is the growth charts. I would focus on a child doing more daily movement in the form of non-exercise activity before we look at structured exercise.”

Movement is very important for kids during the COVID-19 pandemic, adds Dr Nancy, “it boosts the immune system, it reduces stress and anxiety and improves sleep.”

Ultimately, this is what worked for Dubai-based mum-of-two Nadine Sabbah and her daughter. They decided to hire a personal trainer for the 10-year-old, who was trained not only in fitness but also nutrition and psychology. His fun and active sessions worked wonders for Nadine’s daughter’s mental and physical health, and she is now back to her old self again.

“I would advise all parents to involve their kids in physical activities,” says Nadine. “It is good for their mental health, not only for their physical fitness. Never focus on the kid’s weight, but just engage them in more activities. Let it be your own lifestyle as well as and theirs.”

5 WAYS TO HELP YOUR CHILD MAINTAIN A HEALTHY WEIGHT

- Be a good role model

- Encourage 60 minutes, and up to several hours, of physical activity a day

- Keep to child-sized portions

- Eat healthy meals, drinks and snacks

- Give them less screen time and more sleep

"This is not to say that the child does not have disordered eating patterns/behaviour prior to this. However, to be classified as an “eating disorder”, the individual does need to meet this set criteria.

"Key to remember is that we do not have to wait until someone meets this criteria to access help. It is far more helpful to access support prior to this, in order to take more of a preventative approach vs. crisis management. Also, the quicker we address disordered eating patterns, the quicker the individual is able to recover.

"Disordered eating patterns become habitual very quickly, thus prompt intervention can have a significant impact on success and is always recommended.

"Unfortunately, families often wait to address eating-related concerns, hoping the child will “grow out of them”, however this can cause more harm in the long-term, and mean that a higher level of intervention or duration of intervention is needed."

Recurrent episodes of binge eating define a binge-eating disorder. An episode of binge eating is characterised by both of the following:

o Eating in a discrete period of time (for example, within any two-hour period), an amount of food that is definitely larger than most people would eat in a similar period of time under similar circumstances

o A sense of ‘lack of control’ during the ‘over-eating’ episode (for example, a feeling that one cannot stop eating or control what or how much one is eating)

The binge-eating episodes are associated with three (or more) of the following:

o Eating much more rapidly than normal.

o Eating until feeling uncomfortably full.

o Eating large amounts of food when not feeling physically hungry.

o Eating alone because of feeling embarrassed by how much one is eating.

o Feeling disgusted with oneself, depressed, or very guilty afterwards.

o Marked distress regarding binge eating is present.

o The binge eating occurs, on average, at least once a week for three months.

o The binge eating is not associated with the recurrent use of inappropriate compensatory behaviour (for example, purging) and does not occur exclusively during the course of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder.