How the Bhatia business started

A hot and dusty day in Dubai. A scraggly youngster struggled to balance the rolls of cloth on his shoulders as he shuffled into the palace premises. There weren’t security men around. After all, this was the 1920s: a time when Dubai was a desert outpost by the creek.

Some palace maids noticed the skinny delivery boy. He was too young to work. Too frail to carry the cloth rolls. He certainly bore the marks of maltreatment. This aroused the curiosity of the maids, who quizzed him. His has been a life of struggle and abuse at the hands of his employer (a relative) since he came to Dubai, aged 11.

The Sheikha promised to help the lad set up a business on the condition that he learns Arabic.

The maids informed the Sheikha of the youngster and the cruelty he suffered. Sheikha Hessa Bint Al Murr, the wife of then Dubai Ruler Sheikh Saeed Bin Maktoum Al Maktoum, was a considerate lady. When she heard of the abuse and torture of the boy, the Sheikha decided to do something about it.

Sheikha Hessa’s lifeline for 15-year-old Uttamchand

Sheikha Hessa summoned the boy. Why don’t you do some work on your own? She asked. No money, was the mumbled reply. The Sheikha promised to help the lad set up a business on the condition that he learns Arabic. The Sheikha and her employees in the palace taught him Arabic, and during the sessions at the palace he ran into Sheikh Rashid Bin Saeed Al Maktoum, the son of Sheikh Saeed and Sheikha Hessa. The two were around the same age, and a friendship blossomed. Sheikh Rashid called him Vattra (something special, in Arabic) as they became close friends.

In less than a year, the boy became fluent in Arabic. In a few years, a new textile shop opened for business at the creek in Bur Dubai. People called it the Vattra’s Shop. It was only natural since all shops in those days were referred to by the owner’s name. The business was good. At 15, Uttamchand Tulsidas Bhatia the orphan from Sindh became Vattra a textile merchant in Dubai. And that was the start of four generations of the Bhatia family business.

How trade sprouted in Dubai

Uttamchand was not the first Bhatia businessman in Dubai. Nor was his employer Lalchand Dhosani, the son-in-law of Uttamchand’s aunt in Sindh, Pakistan. At least two generations of Bhatias had conducted trade in the 1800s in the region.

At the turn of the century, Lingah on the Straits of Hormuz was a favourite port of call for Indian traders. Business flourished as large boats ferried textiles, grains and spices from India. But anger and frustration seeped into the community when the Lingah ruler imposed taxes. It threw trade into disarray, and traders were staring at an uncertain future.

That was when Dubai Ruler His Highness Sheikh Maktoum Bin Hasher Al Maktoum invited the Indians to relocate to Dubai. The Indian businessmen responded to the overture in 1894, and soon the first shoots of trade sprouted in Dubai.

Nagar Thatta, a small port near Karachi, used to be popular with the Arab merchants who came to sell dates and pearls in exchange for foodstuff and clothes. The Arabs invited the Bhatias to do business in the Gulf. And the Thattai Bhatias sailed from Sindh to set up trading establishments in the region.

Sharjah was a business hub. From there, camel caravans travelled to Abu Dhabi, allowing traders to sell their wares: mainly textiles and foodstuff like rice, wheat, pulses, jaggery and spices, which used to be freighted in from Karachi and Bombay (the present day Mumbai) in cargo vessels called launches.

During the 12-hour desert trips from Sharjah to Abu Dhabi on camels, Dubai used to be a transit point for merchants. Dabai, as it was known earlier, was the place where they rested, relaxed and resumed their journey. During a stopover in the 1920s, Sheikh Saeed called on the traders and asked them to set up operations in Dubai. The Bur Dubai Creek was soon bustling with vendors and buyers

Business thrived with traders from Iran and Iraq jostling for space. The Bhatias were there too. Uttamchand’s employer was one of them. Besides textiles and foodstuffs, cattle and even drinking water were imported. “The deals at the souq were confirmed by the Ruler using a ring seal,” said Deepak Bhatia, who referred to the accounts maintained by his grandfather Uttamchand.

Gold too was in demand. Merchants from the Junagadh district of Gujarat were the leading traders, and Chottu Bhai Soni was the biggest of them all. There were so many Indian businesses by the creek, and hence the place was called Souq Al Baniyan (Traders Market). It is now named Souq Al Kabir, but popularly known as Old Souq.

Drinking water had to be imported from Basra, Iraq. Four-gallon containers full of river water would be ferried to Dubai.

Textile tycoon’s pearl trade

Uttamchand focused on selling textiles. Khadi, the handwoven cotton cloth, was the bestseller. Called Kalak Al Gandhi after Mahatma Gandhi (Father of India, who popularised it), khadi was the cloth of choice of the wealthy. A cheaper material called madhar paat was preferred by the less affluent. All the textiles either came from Karachi or Bombay (present-day Mumbai).

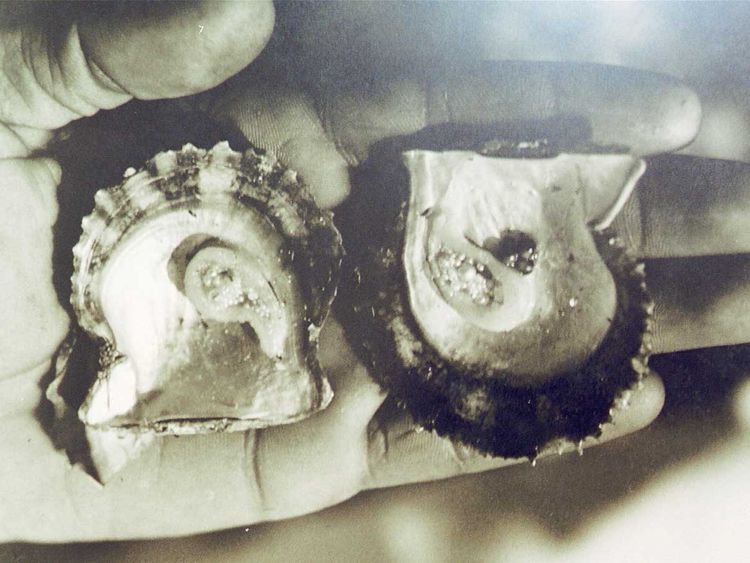

The textile business was booming, but the pearl trade was gathering steam. Uttamchand smelled a business opportunity. In the early 1930s, he rented boats and sent divers (called nakhudas) to the Basra coast in Iraq to dive for pearls. Later the Bahrain coast became a favourite with the pearl divers.

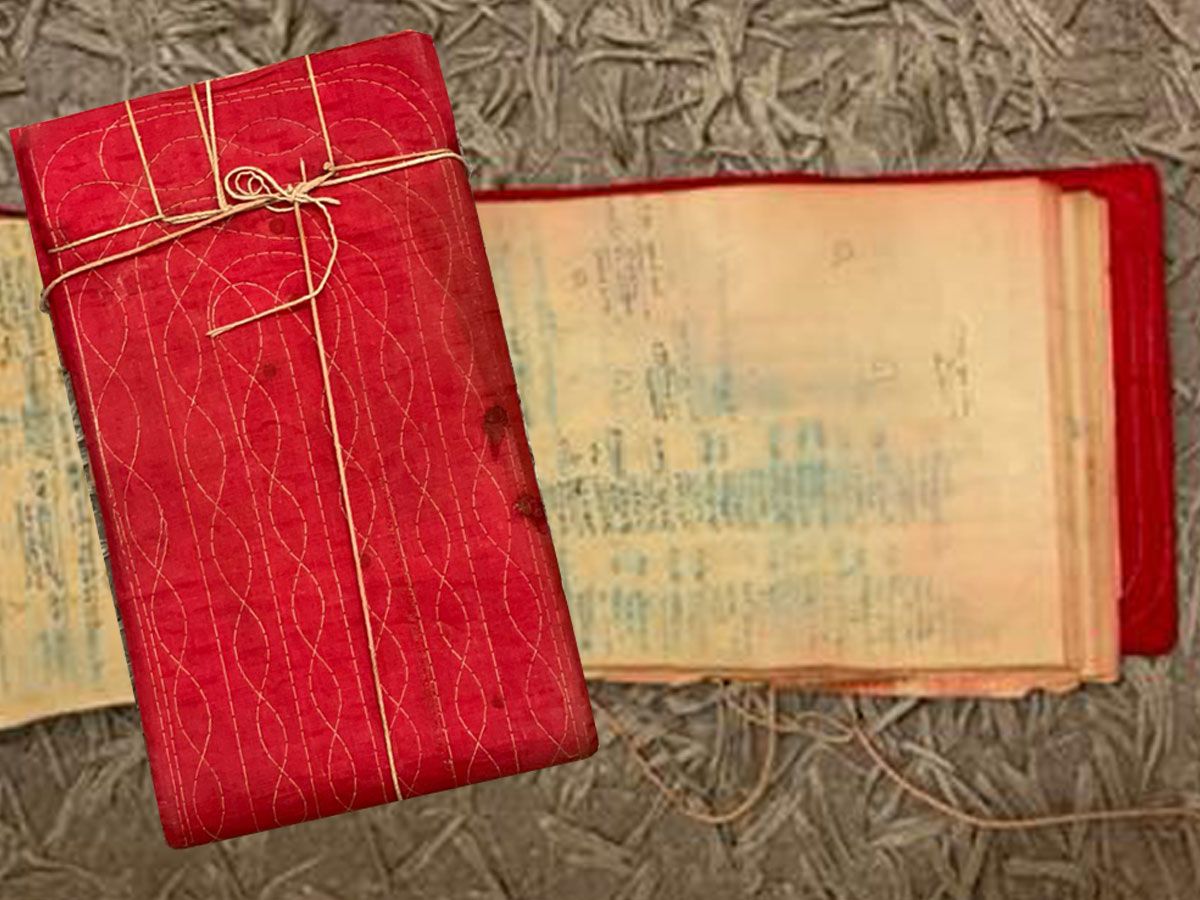

It turned out to be a smart move. He soon became the wealthiest Indian merchant in Dubai and was nicknamed Baniyan Lulu (means Indian pearl trader). Pearl traders often sought financial assistance and loans from Uttamchand. “Pearls raked in money, but textile business continued to be the mainstay for my grandfather,” Deepak said, adding that people trust him with their money saying it safer than the bank. Uttamchand diligently maintained an account on all transactions in a long red book.

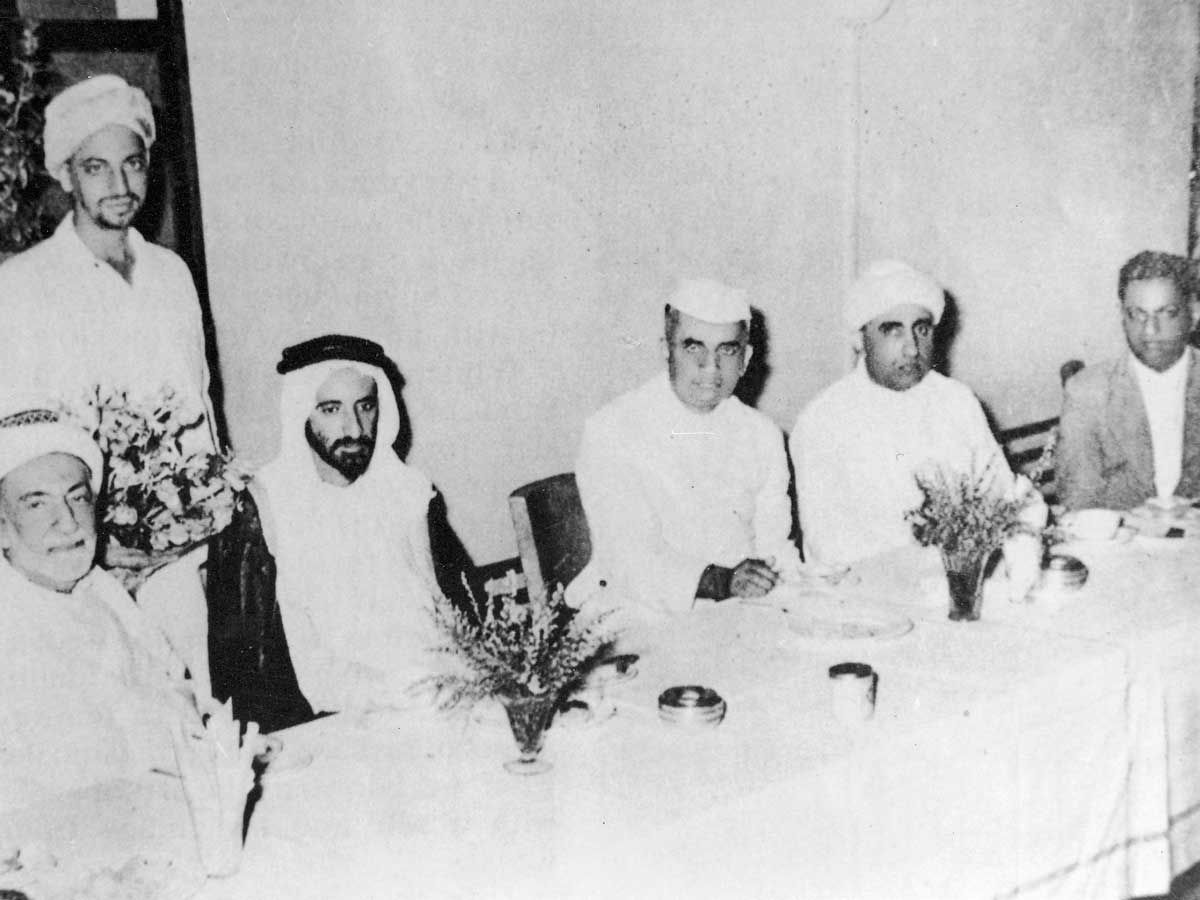

“Uttamchand was the doyen of Indian businessmen,” said Mirza Al Sayegh, director of the office of the late Sheikh Hamdan Bin Rashid Al Maktoum, who was Deputy Ruler of Dubai and Minister of Finance, recalling the contributions of the Indian community in Dubai. “We didn’t regard Indians as foreigners. The relationships were like friends and neighbours. I remember those days with the fondest of memories and remember Vattra as a man who forged a strong bridge between the locals and Indian community in Dubai during this wonderful era,” he told Gulf News in an exclusive interview.

Sheikh Rashid remained Uttamchand’s friend and patron. Uttamchand was Vattra to Sheikh Rashid and other Emiratis, Uttra to Iranian traders and Uttara bha to Indian merchants. [Some Indian communities refer to the community head as bha]

“Those days, the shops were on the ground floor, while the traders lived in houses on the first floor, called gurfas. Many of the shops by the creek faced each other and were barely four feet apart,” Deepak said, recalling the narrations from his grandfather.

“Sheikh Rashid was a man of extraordinary business acumen, but at heart he was a simple man of simple habits,” Uttamchand had told a publication.

When Sheikh Rashid realised that the grain re-exports to Bahrain and Oman were rewarding, he seized the opportunity. And the foundation of the Dubai re-export business was laid in the 1960s, according to a report which cited Sheikh Rashid’s swift move to clear the silt from the Bur Dubai Creek was to facilitate the entry of dhows which were integral to the re-export business.

This was attested by Mirza Al Sayegh, director of the office of the late Sheikh Hamdan Bin Rashid Al Maktoum. “Sheikh Rashid in 1961 dredged the creek so that bigger vessels could come in. Three years later, when there was a need for bigger port, the work Port Rashid began,” he added.

Port Rashid was inaugurated in 1972, and remained Dubai’s commercial port until 2018 when cargo operations were moved to Jebel Ali port. The deep sea Jebel Ali port was inaugurated in 1979 by Queen Elizabeth.

New business avenues

By the 1930s, the pearl trade began to lose its lustre. The demand for natural pearls dwindled with the arrival of cheaper cultured pearls from Japan. The Second World War hastened the death of the pearl trade.

In a world wracked by conflict, new business opportunities arose. Uttamchand took note of the considerable demand for foodstuff. The textile merchant and pearl trader soon branched into the retail food business after Sheikh Saeed gave him special permission to open a provision store that sold goods at controlled prices. Supplies to the store at the abra station came from Karachi and Bombay.

Uttamchand dabbled in gold trade too, rather infrequently. Divers and traders continued to sell him pearls of exceptional quality. He never sold them. Those went into his collection, became part of the family heirloom.

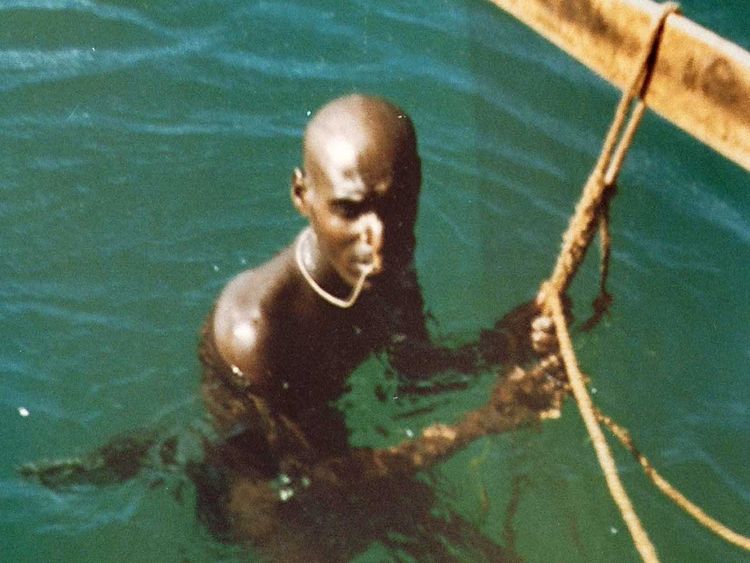

The diving season ran from May 15 to September 15 each year. Only 300 locally-made boats were available in Dubai, Sharjah and Bahrain. They could be hired for 1,000 to 2,000 rupees for each boat. Groups of 20 nakhudas (divers) travelled on these boats with three and a half months’ rations (rice, water, etc.) to Basra or Bahrain.

Diving was tough. With wooden nose-clips and stone weights, they plunged deep to the seabed to bring back oysters. Not all of them contained pearls, yet there were enough pearls to run a lucrative trade.

Secrecy was the key to pearl business, so traders struck deals in a strange manner. The buyer and vendor tucked their hands under a cloth and felt each other’s fingers to decide on the price. This allowed the transactions to remain secret, and even if the deal fails to materialise they could walk away without divulging the price. Peculiar it may be, but it worked for the traders.

Some pearl merchants borrowed money and rented the boats to send the divers to fetch pearl-laden oysters from the seabed. After deals were done with the pearl buyers (tawas), traders gave 10 per cent of the profit to the financier besides the loan amount. The government received a share (equivalent to a diver’s take).

New beginnings after Second World War

After the Second World War, Uttamchand returned his focus to textiles. The war had an impact on people and their purchasing power. So the business was slow. Demand for cloth perked up over time as people preferred to buy from Vattra’s Shop.

China silk soon became popular. It was sold at between 2.50 to 4 rupees a roll. Japanese textiles and synthetic cloth too were introduced into the stock. Sales soared, Uttamchand was smiling again. But he yearned to return to India.

A business blip in India

Long years away from India kindled a longing in Uttamchand. A longing to spend time in India. But the India he knew had changed: the Partition has divided the country into India and Pakistan. Many of the Thattai Bhatia families had moved to India from Sindh. Uttamchand wanted to go to India to explore the prospects of starting a business.

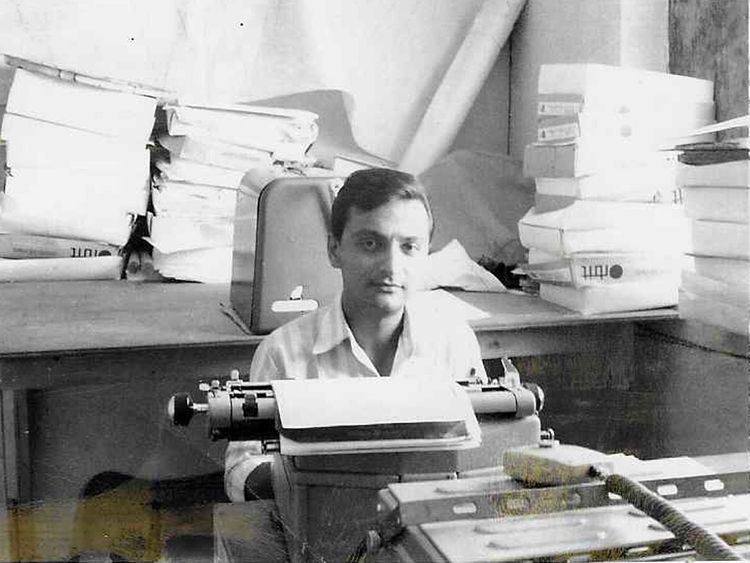

In the early 1950s, he drew up a plan that allowed him to stay in Bombay for long periods. Three of his assistants were entrusted with running his shop, as he remained in India for some time, making shorts trips to Dubai to check on his business.

Uttamchand’s India sojourn turned sour. His business activities ran aground. His cousin Issardas Bhatia started a building construction business in Bombay with Uttamchand as his partner. Issardas later became the first construction moghul in Bombay as he revolutionised the sector by introducing the right to own apartments. But in the early days, the business suffered massive losses. A rare setback for Uttamchand. He called it quits.

Emotionally too, Uttamchand seemed to have suffered. “I felt an alien in what they told was my country,” he’s reported to have said.

Undeterred, Uttamchand returned to the familiar terrain of Dubai and spruced up Vattra’s Shop. His presence reinvigorated the business, and the shop was buzzing again.

The discovery of oil in 1966 catapulted Dubai from a sleepy village into a throbbing town. More people started coming to the emirate, and the demand for goods soared. Other trader communities too arrived from India and other places to set up shops. The business was good. Uttamchand loved it. Far away from his homeland, he felt happy and welcome in a country, which afforded him opportunities to grow. He remained grateful for that.

Uncle’s Shop is born

After the Dubai Municipality was established in 1954, new laws were drawn up to streamline the growing business operations in the emirate. Shops didn’t have names; they used to be referred to by the owner’s name. But the new laws in the early sixties insisted on names and trading licences for shops. So Vattra’s Shop became Uncle’s Shop.

How did it get the name? Sheikh Rashid used to be a frequent visitor to the Uttamchand house. Uttamchand’s children used to call Sheikh Rashid “Uncle”. As a symbol of his friendship and loyalty to Sheikh Rashid, Uttamchand named his shop Uncle’s Shop.

Uttamchand’s son Vijay continued to do business from the premises although he had diversified his portfolio.

Sons and businesses of Uttamchand Bhatia

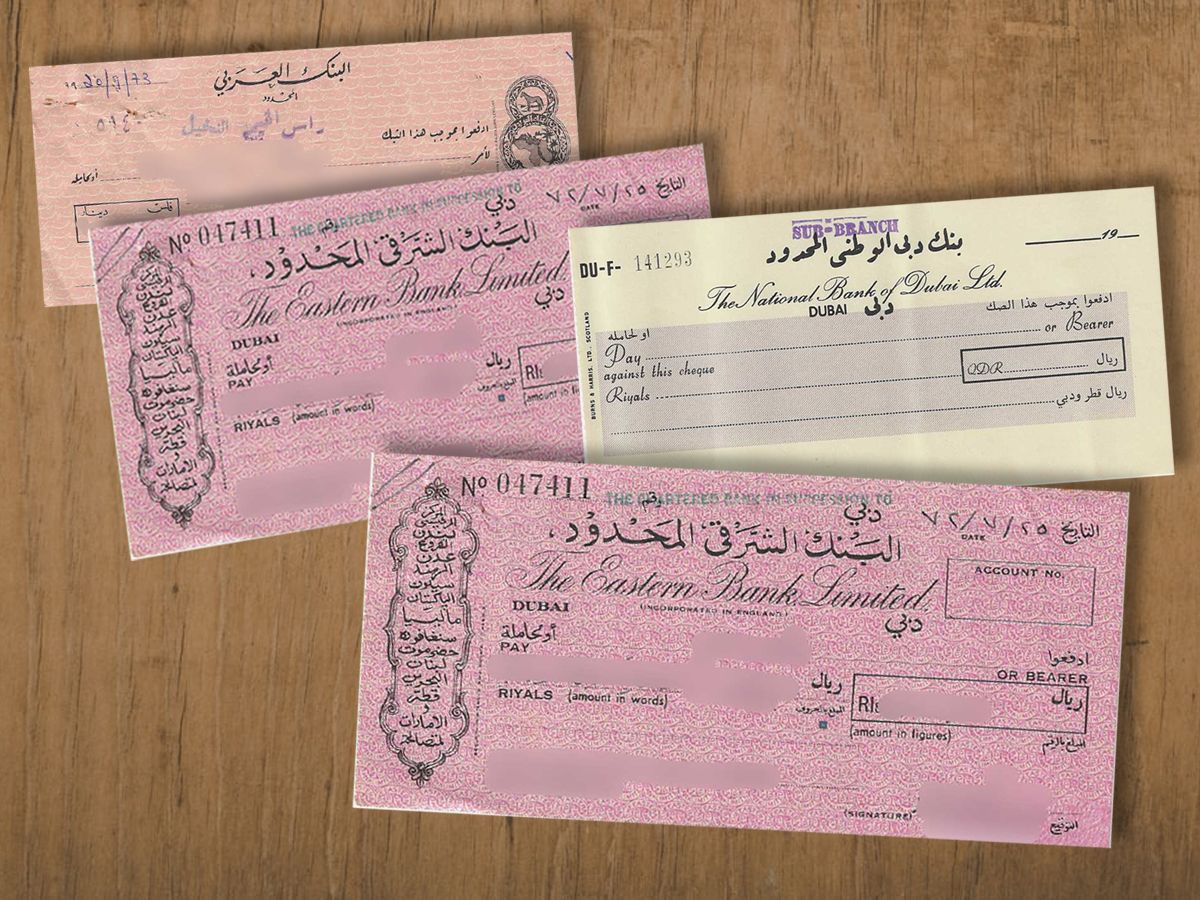

Uttamchand’s first-born Paramanand built a career away from textile business. A commerce graduate, he joined the Eastern Bank in Buraimi, Al Ain, in 1963. His successful banking career was cut short seven years later when health issues forced him to return to India.

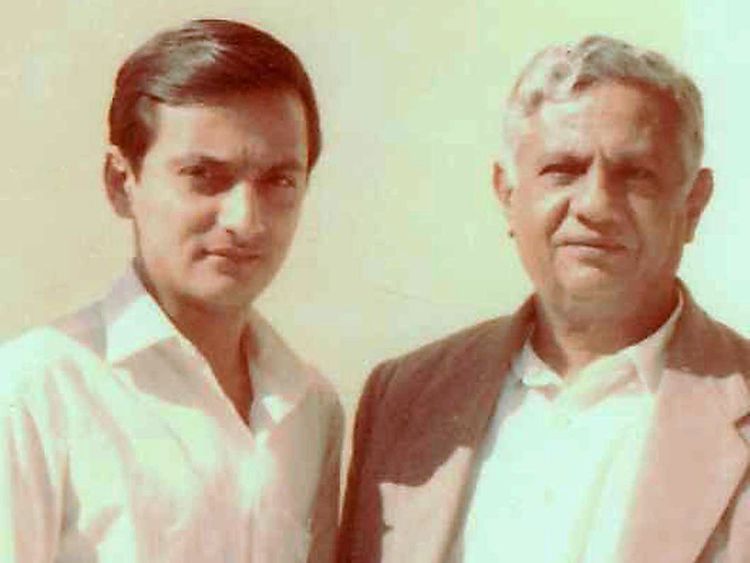

Unlike Paramanand, his brothers Vijay and Ashok joined the family business only after their marriages in 1969 [The weddings were on the same day in Bombay]. The two had stints with Pauling & Co, a major British civil engineering contractor, in Abu Dhabi in the early sixties. That helped them learn about road work and construction.

“Grandfather didn’t want his sons to join his business straightaway. He sent my father and uncle to work in Abu Dhabi. It was a kind of training to prepare them to take care of the family business in the future. Living together away from the family also helped them become independent and responsible,” Deepak said of Uttamchand’s decision.

A new country and new opportunities

December 2, 1971. The United Arab Emirates was formed. Abu Dhabi Ruler His Highness Sheikh Zayed Bin Sultan Al Nahyan became the president and Sheikh Rashid the vice-president. “Nine emirates were called for the talks to unify the country. The rulers met repeatedly, but finally Bahrain and Qatar withdrew. The UAE was formed with six emirates, and Ras Al Khaimah joined later,” Al Sayegh said, recalling the birth pangs of the federation.

Uttamchand continued to look out for business opportunities. He saw the potential in the real estate sector, and he’s had experience earlier when Sheikh Saeed allowed him to buy property. So when Sheikh Rashid permitted him to invest in property in Dubai, Uttamchand diverted his energy to it. This was long before the days of freehold property. Uttamchand was overjoyed at the Ruler’s decision. “I’m not an expatriate, I’m an immigrant,” he’s reported to have said.

He no longer entertained any thoughts of expanding his business to India. Uncle’s Shop in Dubai continued to flourish. Textiles were always in demand in a new nation that began to attract visitors. But Vijay and Ashok diversified the family business: Ashok moved into retail petrol sales through Caltex pumps, while Vijay made forays into the construction and film distribution business.

How the Iran-Iraq war nearly killed the textile business

The eight-year war between Iran and Iraq from 1980 has had a drastic effect on trade in the Middle East. The business in Dubai suffered too. For, Iranians and Iraqis were among the prominent businessmen. Moreover, Basra in Iraq and Bushehr in Iran, two of the main trading posts in the region, could not send consignments to the UAE.

The hostilities made the waters of the Arabian Gulf unsafe for shipping. Fewer cargo vessels arrived at the Dubai port. Imports were severely reduced. Textiles suffered the most. The Bhatias were fortunate. By then, they had diversified their business. But the family was rocked by a tragedy.

A big blow to the Thattai Bhatias

May 16, 1986: Uttamchand paid a visit to Sheikh Rashid ahead of a trip to India. A reluctant parting followed a long meeting. Uttamchand was to fly the next day, but a pilot suffered a heart attack, and the night flight was delayed by four hours.

He reached Bombay in the early hours of May 18. Barely did he clear the immigration at the airport, Uttamchand collapsed. The founder of the Thattai Bhatia family business in Dubai suffered a fatal heart attack.

Uttamchand was cremated in India. That was his desire.

Life after Vattra: Business beyond fabrics

Four years after Vattra’s death, Sheikh Rashid too passed away. But the Dubai ruling family’s ties with the Bhatias remained strong. Vijay Bhatia steered the Uncle’s Shop, and he believed that the Bhatia business future lies beyond the fabrics. Under his stewardship, the Bhatias explored newer avenues.

There was a paradigm shift in the Bhatia business strategy.

Besides textiles and readymade garments, Vijay had business interests in construction and film distribution. His son Deepak joined the family venture after a stint at an aviation company. He too wasn’t enthused by textiles, so he worked to add steel and timber to the trade profile.

It wasn’t easy. The moorings in textiles business were strong, but steel and timber were new frontiers. Deepak spent a great deal of time learning the tricks of the new trade. In 1996, he struck pay dirt, clinching his first deal: an agreement to import and distribute plywood from Indonesia. That buoyed his confidence and two years later, Deepak entered the steel business.

The building material business prospered as Dubai grew into a major city. The demand for construction materials kept rising. By the turn of the 21st century, Deepak was selling around 600 products, all catering to the construction sector. Cement boards were a big seller and a major driver of Deepak’s trade.

Dubai was growing at a rapid pace. Deepak was quick to notice it. He was amazed by the speed of Dubai’s development under its Ruler His Highness Sheikh Maktoum Bin Rashid Al Maktoum and Crown Prince His Highness Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum. There was construction activity everywhere: residential towers sprouted in new areas, freehold property took off in a big way, roadworks seemed endless, and infrastructure expanded at a breathtaking pace around the emirate.

Deepak tapped into major government projects to fast-track the growth of the Bhatia business. The Dolphinarium, which was completed in 2001, was Deepak first major project. After that, there was no looking back. Dubai’s ruling family lend support as Deepak helmed the Bhatias’ drive towards infrastructure projects.

The projects and products won the seal of approval from the Dubai authorities. Significant among was Dubai Civil Defence’s approval for fireproof boards in 2019. The same year Deepak’s company introduced electric roofs that integrated solar panels into cement boards. “We were the first in the world to do it,” he said

More projects followed. The Dubai airport expansion, the Dubai Metro, the Dubai Mall expansion, Dubai Parks and Resorts: Deepak Bhatia supplied materials to all of them. Many more are underway, like the renovation of the QE II and the entrance plaza and other major projects at the Dubai Expo.

The patronage of Al Maktoums

Deepak credits the Dubai ruling family for the Bhatia success. “Even after grandfather’s death, the relations remained strong. We could not have done without the patronage and the privileges bestowed by the royal family. It has helped in our business and gave us bigger than expected benefits. For that, I remain grateful,” Deepak said.

Uncle’s Shop exists, but not by the Dubai Creek. It now sits in a swanky premises near Rashidiya. The Thattai Bhatias run their business from there. But it no longer sells textiles. Building materials are the new textiles.

A fourth generation Bhatia in Dubai

2020 was the year of the coronavirus. A year when economies around the world were battered. Vaccines have given us hope in 2021, and the Bhatias took the opportunity to unveil their scion. Yash, a fourth-generation Bhatia, joined the family business. Following the family tradition, he too opted to gain experience elsewhere. An internship in an international bank was followed by some exposure to automobile business. Now, Yash Bhatia says he’s ready. He has joined his father to become the new torchbearer of the Bhatia business.

How does a young man with a passion for cars and cooking fit into the construction business? Yash is under no illusions. He says it will take a while to learn the trade before playing an essential role in advancing the family business.

Yash is aware of his great grandfather’s reputation and his significant role in developing business in Dubai. “It’s an emotional moment for me. A proud one too. I’ve heard about his [Uttamchand’s] honesty and how he maintained relations. I’m very keen to continue the family legacy,” Yash said.

Textiles, pearls, foodstuff, real estate, readymade garments, petrol retail, film distribution and construction materials, the Bhatia’s have been involved in a gamut of businesses. Diversification helped. What would Yash add to the family portfolio? “I would like to get into the hospitality industry someday. Green energy products and sustainable solutions are also part of my plans. But I don’t want to start a business from scratch without indepth study. I need to have a clear picture,” the business management graduate said.

These are early days for Yash Bhatia. Maybe, in the days to come, Yash will chart a new course for the family business. At 26, he’s got time on his side.