The hotline rang exactly at midnight. A concerned Abu Dhabi resident called to report a large charcoal grey-hued bird walking around in the balcony of their 10th storey apartment, looking particularly stressed.

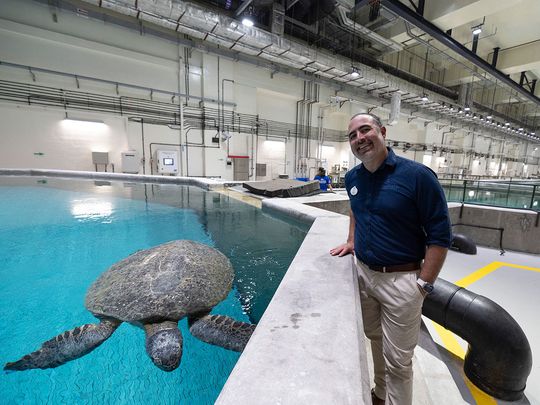

Jonathan Diaz, Zoological Senior Manager of Rescue, at the Yas Seaworld Research and Rescue center, immediately deployed his rescue team, successfully bringing back the marine bird to their facility, where they conduct such operations on a daily basis. Upon examination, the bird turned out to be a Socotra Cormorant – a threatened species in the region.

Engaging the community

Diaz helps operate the region’s first marine wildlife rescue ambulance service.

Whether it’s a stranded sea snake a beachgoer finds or a lost marine bird roaming around in someone’s backyard, Diaz manages the calls that the centre receives on their hotline number – (056)5030060, ready to save injured or lost marine wildlife found across Abu Dhabi and its islands.

The service has given UAE residents a quick way to report these incidents and be a part of the efforts the nation is putting into protecting marine life.

“Calls we get come from people at the beach and concerned boaters who secure the animal[s] and drop them off at our centre,” Diaz said, who came to the UAE two years ago to join the facility, and has worked in marine animal rescue for over 20 years.

Conducting rescue operations

“Once we get a call, we take our ambulance to the rescue site. Our ambulance has a capacity of 6000 kilograms,” he said.

Describing a typical rescue operation, he said: “We first get a call on our rescue hotline - something we carry with us throughout the day. When someone calls, we are looking for certain information that’s going to help us determine how we are going to perform the rescue operation. We typically ask what type of animal it is, why the person thinks it needs to be rescued, and some location information. We ask for a picture and that picture helps us determine what process we will go through.

“If it’s a large animal, it’s going to require different resources than a small sea bird. We are fortunate here to have a variety of vehicles – a large wildlife ambulance, a midsize ambulance, and pickup trucks. Depending on our needs.”

A look inside the ambulance

Diaz gave us a look inside the large wildlife ambulance, designed uniquely to fulfill the needs of distressed marine animals.

“They keep it [the ambulance] largely empty with only equipment that they would need depending on the type of animal they are rescuing and the conditions in which the animal is,” said Diaz.

“It’s also because animals sometimes move a lot, so we don’t want them getting injured and rubbing up against something built into the ambulance,” Diaz said.

The bottom of the ambulance is also lined with a mattress-like sponge material so that the animals are comfortable. Diaz explained that some animals, who are used to living in water, have skin that is not accustomed to hard surfaces, so they need extra care.

Some of the other items in the ambulance are medical equipment, a net to catch animals, and a snake stick in case it’s a sea snake that needs help. And these pieces of equipment are changed around every time the team heads out. For instance, they need to consider whether the nets are big enough to hold a particular animal or whether a holding pool is the right size.

No day is the same

Thinking about catering to the needs of each animal and problem solving does not end at the rescue stage. They have to think out of the box and come up with practical solutions even at the facility’s hospital, making each day different.

Dr Tre Clarke, Director of Animal Health and Welfare at the Yas Seaworld Research and Rescue center, experiences this often first hand.

“What’s consistent about our day is the inconsistency about our day,” he said. For his team, who’s responsible for the marine animals once they are rescued, no day is the same, as Clarke perfectly puts it.

“We could see an injured fish all the way up to looking at a flamingo, or looking at a cetacean, or broken [injured] seagulls that come in or sea turtles,” he said.

Clarke and his team are responsible for the treatment, diagnostics, and rehabilitation of the animals up to the point that they are declared ready to be let back out into their wild environments.

His day usually starts at 8am. He looks at the schedule for all the animals he needs to visit and gets updates from the keepers, trainers, and rescuers. He calls them his “eyes and ears” because of the proximity they have with the animals.

“Animals don’t want to seem injured. That shows that they’re prey for somebody else,” Clarke said.

The team needs to conduct tests to find out what’s wrong. “Unlike humans, animals don’t really tell us what’s wrong with them so we have to do an investigative research, play a little Sherlock Holmes. I also go into meetings, check the husbandry needs for the animals for us to rehabilitate them,” he added.

Working with wildlife

Besides helping the animals, one of the daily tasks Clarke needs to take care of is to keep the workers at the facility safe and that’s tricky when they work with wildlife.

“As a doctor, we are responsible for not only the patient but also for the people in the room. So we have to remember these animals are not your pets, they are not your dogs or cats, they are wild animals, and they can be and are dangerous. So it’s important for us to control that situation and keep everybody safe. My day starts with seeing the animal list and coming up with a plan to not only protect the animals but also the people,” he said.

Animals have different types of faces and we can’t just use a simple mask. We have to sometimes make these things bespoke. We have taken a traffic cone and used that as a mask to anaesthetise animals, two-litre soda bottles to fit different beaks and bills of birds, so my day consists of what I can create to ensure the health and safety of the animal and also the people who are working with them.

Part of that process is improvising and problem solving.

“Animals have different types of faces and we can’t just use a simple mask. We have to sometimes make these things bespoke. We have taken a traffic cone and used that as a mask to anaesthetise animals, two-litre soda bottles to fit different beaks and bills of birds, so my day consists of what I can create to ensure the health and safety of the animal and also the people who are working with them,” he said.

Assess and treat

Besides using bespoke methods, he works with the hospital’s medical equipment to scan, monitor, and treat these animals.

“When we first receive the animal into our research centre and hospital, we are able to monitor the animal and look at it. Because if the animal is rescued, it’s typically sick or injured and one thing that we want to do is assess what’s going on with it, what’s the mental status of the animal, is it broken, is it fractured, or is it emaciated?” he said.

These are the important questions they need to ask so they get an overall picture of the animal’s health. From there, they have a number of diagnostic equipment they use.

“If we are dealing with an animal that is highly stressed out, the most important thing is to anaesthetise the animal with our anaesthesia machines. We can monitor the heart rate, the internal CO2 (carbon dioxide), and the amount of oxygen within the blood. We have ultrasound machines to look inside their bodies to see if there’s anything amiss. If there is free flowing fluid or blood or lacerations,” he said.

“In case we have large animals, we have a large animal anaesthesia unit – we can handle anything like large cetaceans or dolphins. We are able to handle those and get them under oxygen.

“We have an endoscopy machine that essentially has a camera on the end of it. It’s an arm with a camera that looks inside the animal through its mouth if, for example, it has swallowed any trash or anything that we need to get out,” he added.

Reducing stress by mimicking their natural environment

As Clarke mentioned, a lot of these animals that come in are much stressed – the team at the rescue centre considers it important to reduce that stress as much as possible.

“We can accommodate any type of species that come through our doors. Let’s say a bird comes in, there are special built-in rooms that are air and temperature controlled, have nesting posts, and we try to recreate its hiding spots. Let’s say, it’s the spotted crake that we brought in, which is a marshland bird, we brought in big tubs of grass and little huts for it to hide in, and feel safe and secure. We used a kiddie pool for it to be kept,” Clarke said.

“If we have a sea turtle that comes in, we have large pools that can accommodate those animals with floors that lift that are able to bring the animal to the surface of the water to us rather than catching the animal each time we need to look at it.”

Currently, one of the pools, which is around five metres deep, is holding an 80 kilogram female green sea turtle, struggling with buoyancy issues.

Another way the medical team and rescue staff at the facility reduce stress is by having lights that mimic Abu Dhabi’s natural light cycle around their indoor holding pool areas.

“The lighting system is accustomed and in tune to whatever lifecycle we want it to be. Right now, they are following the Abu Dhabi lifecycle so they will dim naturally when it gets dark outside. They provide full spectrum lighting… that’s for every animal enclosure here.”

Collaborating with authorities and educating the public

The team also collaborates with UAE authorities, such as the Environment Agency – Abu Dhabi (EAD), to provide feedback, research, and crucial data on the marine life in the region.

“Once an animal comes in, we are able to monitor and assess it, and hopefully we rehabilitate the animal and get it back to health, so that we can return it to its natural environment. Some of this information is really pertinent to help this not happen again. So, we are giving this information to the authorities. We are working very closely with the environment agency of Abu Dhabi. We are giving them this solid data on what type of injuries they are receiving and giving this data to the officials will allow them to make the right decisions and help regulate policies that can impact those animals in a positive way,” Clarke said.

Once an animal comes in, we are able to monitor and assess it, and hopefully we rehabilitate the animal and get it back to health, so that we can return it to its natural environment.

Speaking about the common reasons marine animals get injured and end up at the facility, Clarke said: “One of the most common things is human interference. Getting run over by boats, ingesting foreign objects like trash, fish hooks, and fishing lines. Animals that were not able to find food and get emaciated, fell sick, there are a wide host of different reasons why animals come to our hands.”

Spreading awareness about these issues is one of the aims of marine animal rescuers, such as Clarke.

“If we don’t educate the public like you and me, they might do the same thing to the wildlife and could hurt them again,” he said.

“The more we can educate people about what’s going on in our environment and how we can help animals, the better those animals will be and they wouldn’t even have to come here. And that’s really the best rescue program. If we don’t have to see anything, we are doing a good job.”