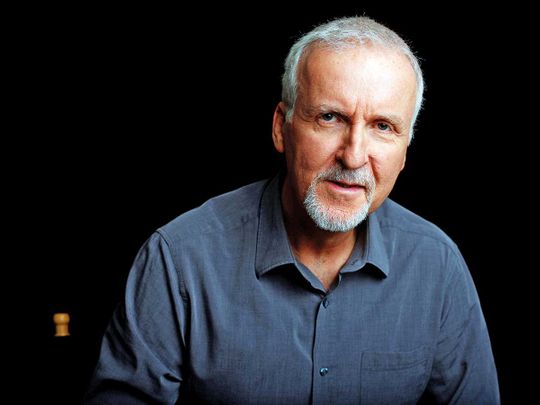

Nearly 13,000 feet underwater, James Cameron was again tucked inside a submersible vessel toward the bottom of the North Atlantic on one of his many dives documenting the Titanic. But as the crew finished its dive near the wreckage of the 1912 tragedy that killed an estimated 1,500 people, Cameron and his colleagues had no idea of the American nightmare that awaited them on the surface.

The date was Sept. 11, 2001.

When Cameron climbed down from the steps of his submersible inside the expedition’s main ship, the “Titanic” director was told what had happened 12 hours earlier: Roughly 3,000 people were killed in terrorist attacks in New York City, at the Pentagon and in Pennsylvania, and thousands more were injured.

“What is this thing that’s going on?” Cameron asked actor Bill Paxton, who starred in 1997’s “Titanic” and would later be part of the expedition for the 2003 documentary “Ghosts of the Abyss,” which toured the ship’s disintegrating wreckage.

“The worst terrorist attack in history, Jim,” Paxton replied.

As Paxton explained to Cameron and the stunned crew about the planes that crashed into the World Trade Centre towers only minutes apart, the filmmaker who dedicated years of his life to bringing both the historical and fictionalized versions of the Titanic story to the world realized he “was presumably the last man in the Western Hemisphere to learn about what had happened,” he told Spiegel International.

The Sept. 11 attacks also forced Cameron to question why crew members were still diving toward the Titanic at that crucial moment in time.

“The day the 9/11 terrorists murdered 3,000 people in New York and Washington, I was just diving to the Titanic,” he told the German outlet in 2012. “For a while, I thought, ‘Why are we diving into history while new parts are made, while the very ground we are standing on is shaking?’”

He added in the documentary, “We were all very wrapped up in what we were doing and we all thought it was desperately important. And then this horrible event happened and slammed us into this perspective.”

One of Cameron’s crew members agreed: “The morning after the attack on September 11th, I kept thinking how trivial this expedition suddenly became. It just wasn’t a big deal anymore.”

Many are now reflecting on the Titanic and the dives to the wreckage as the search for a submersible vessel that vanished on an expedition to the site enters its third day. Rescuers and officials are concerned about the dwindling supply of emergency oxygen that will soon run out for the five people onboard the deep-sea submersible, which lost contact with the Canadian research vessel Polar Prince during a dive 1,450km east of Cape Cod, Mass., on Sunday morning.

Monumental task

Finding the submersible that far underwater has been described by experts as a monumental task. The wreckage of the Titanic, which was touted as unsinkable before hitting an iceberg and sinking in April 1912, now lies on the ocean floor under 12,500 feet of water, roughly 370 miles off the coast of Newfoundland, a province in northeastern Canada.

Cameron’s experience in submersible dives dates back decades. When Cameron signed on to direct “Titanic,” he made about 12 trips to the wreckage on a submersible, according to National Geographic. He recalled to Playboy magazine in 2009 that he made the film “because I wanted to dive to the shipwreck, not because I particularly wanted to make the movie.”

“The Titanic was the Mount Everest of shipwrecks, and as a diver I wanted to do it right,” he said.

Cameron got the deep-sea diving bug and eventually made more than 70 submersible dives, including 33 to the Titanic, logging more hours on that ship than Capt. Edward Smith himself, according to National Geographic. (A submersible is different from a submarine in that it is supported by a surface vessel, platform, shore team or submarine.)

Cameron, who did not immediately respond to an interview request Tuesday, also told the magazine he was aware of the dangers of going in a submersible thousands of feet underwater.

“You don’t want to put a big emphasis on it because you’re there to do a job and stay focused,” he said. “But every time I close the hatch of a submersible I say to whoever is gathered to see us off, ‘I’ll see you in the sunshine.’ Of course there’s no sunshine down there, so to say that means you’re coming back to the surface.”

Paxton, who died in 2017, recalled to the Guardian in a 2002 interview how in August and September of 2001 he was helping Cameron make “Ghosts of the Abyss,” which mimicked the opening sequence in “Titanic.” He was back on the ship and not in the submersibles when some of the crew members found out what was happening hundreds of miles away on land in Manhattan.

“When we first got word, Jim had just gone down with the two subs,” Paxton said, adding that it was the last dive of the day before Hurricane Erin arrived. Cameron and the crew had lost one of their robotic cameras, Ellwood, named for one of the Blues Brothers, and they were attempting to recover it.

Don Lynch, the official historian of the Titanic Historical Society, who was on one of the two submersibles, recounted to the Reagan Foundation how the crew got an “acoustic” call from Cameron’s brother, telling the filmmaker how “there had been a terrorist attack on the World Trade Centre” and “all flights were grounded.”

“These two sentences didn’t seem to connect,” Lynch said in 2017, noting that they believed a terrorist attack was more of a bombing. “We ended up getting so involved in the dive that we pretty much forgot about it.”

When they came back up, Cameron and the crew were excited to talk about how they had retrieved Ellwood. But not long passed before their happiness seemed almost inappropriate given what was happening in the US.

“It was the strangest feeling that I had left the surface, and I had left one world behind,” Lynch said. “When I came back, it was a new planet. It was a whole different world and there was no going back again.”

Paxton echoed the sentiment to the Guardian: “I said, ‘Jim, the world changed from the time you went down till you came back.’ It was strange. We felt a little bit like survivors out there.”

In the days following the 9/11 attacks, Cameron wrestled with why he and others were still doing submersible dives all these years later. But he soon understood that his 1997 film - an Oscar-winning cultural phenomenon that made more than $2.25 billion at the box office - offered a blueprint for how people could cope with a tragedy with a death toll twice as high.

“Some days later, I realized that ‘Titanic’ gave us help in interpreting the new disaster, in exploring the feelings of loss and anger,” he told Spiegel International. “Why do people watch ‘Titanic?’ It’s partly because they can cry. Loss is a part of our life; it’s about love and death and about death partly defining love.

“And these are things we all have to cope with.”