Beirut: The 1989 Taef accords led to the end of Lebanon’s civil war but have since become a by-word for the kind of sectarian-based governance that many protesters feel needs to be scrapped.

The protests sparked on October 17 have spread across the country and quickly grown into an unprecedented cross-sectarian street mobilisation against the political class.

But to understand the current protests one must understand Lebanon’s complex political history:

What are the Taef accords?

The agreement - signed in Saudi Arabia on October 22, 1989 - was designed to end the devastating civil conflict that started in 1975 and reconcile a deeply divided country.

The accords shaped Lebanon’s political system, enshrining a 50:50 power-sharing balance between Christians and Muslims in parliament, a controversial system which some see as the best guarantee of peace and others as hindrance to true citizenship.

The document affirms Lebanon’s independence, sovereignty and democratic character, and it apportions key positions between the dominant communities, transferring much of the power from the president to the prime minister.

Traditionally, the president in Lebanon has always been a Maronite Christian, the parliament speaker a Shiite Muslim and the prime minister a Sunni Muslim.

Under the agreement, parliament seats are evenly shared by Christians and Muslims.

“Taef has established a set of customs and practises” that amount to a “parallel constitution for Lebanon”, said analyst Ali al-Amin.

Yet several of its key points have been ignored, including the “abolition of political confessionalism”.

“The Taef accords called for the creation of a commission to abolish sectarian politics, administrative decentralisation, the creation of a senate and a number of structural reforms, all of which remained a dead letter,” political analyst Karim Bitar said.

Were they successful?

The accords not only paved the way for the end of the war a year later but also allowed for the demobilisation of militias, except Hezbollah, and the reconstruction of the army and country’s infrastructure.

The hundreds of thousands of protesters who have been demonstrating for almost a week initially took to the streets over tax hikes and bad services.

Their main demand now is the removal of an entire political class they say has developed patronage networks to ruthlessly exploit the sectarian system for their own benefit.

“That’s a fundamental break from the past. The Lebanese aspire to a new social contract not based on clientelism and sectarianism,” Bitar said.

Within the Taif agreement there are provisions that match protesters’ demands, but the way it is understood and implemented by the political class is diametrically opposed.

What we are witnessing now is nothing less than the emergence of a Lebanese citizen identity. These recent demonstrations are really unprecedented. From north to south, people describe themselves as citizens who want a direct link to the state - not as belonging to a community that just wants its share of the cake

What are the alternatives?

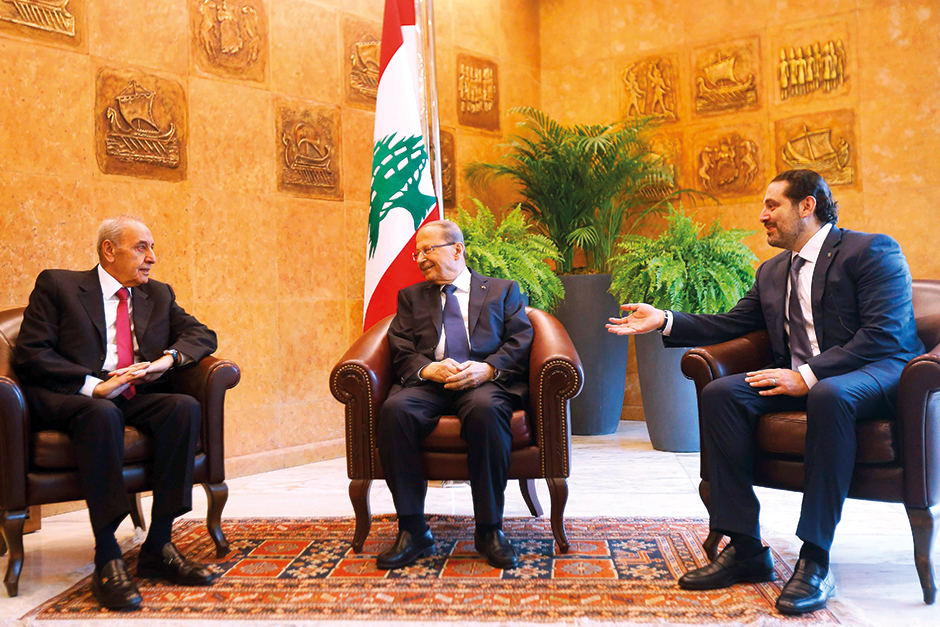

Prime Minister Saad Hariri announced a series of reforms on Monday approved in response to the protests.

But the emergency measures were met with scepticism by many demonstrators, who viewed them as a desperate attempt by politicians to keep their jobs.

“If he had wanted to take really radical measures, Saad Hariri could have announced the appointment of the commission” for the abolition of confessionalism, analyst Karim el-Mufti said.

Putting the Taef accords on the table again is a move many in Lebanon have shunned, saying it could risk sparking sectarian discord.

“Those who still defend the Taef accords today argue that an alternative would be negative and revive debates over the level of representation of each community,” Bitar said.

Hezbollah was not a political force back in 1989, and some parties fear that the Shiite movement would push for a change of the 50:50 ratio to claim a bigger share with a “three thirds” system between Christians, Sunnis and Shiites.

According to Bitar, there is a split “between Lebanese youth - those who are protesting today and have moved into the post-Taef era - and a political class that is bent on preserving sectarian bastions.”

“So this is a limbo. Taef has become obsolete but we still can’t see what could replace it,” he said.