Beirut: Lebanese politicians are eying the premier’s position in Beirut, which has been suddenly left vacant by the October 31 resignation of Prime Minister Saad Hariri.

Speculation is rife on who might replace him, with the names of ex-premiers Najib Mikati and Tammam Salam making the rounds, along with that of ex-Interior Minister Raya Al Hassan, a member of Hariri’s Future Movement.

A fourth name—with little surprise—is Hariri himself, who stands a very high chance of being asked to form a new government, for lack of acceptable alternatives within the Sunni community.

“It’s almost certain that Hariri will be re-appointed premier,” said prominent Lebanese analyst Fadi Akoum.

Speaking to Gulf News, he explained: “His two speeches, followed by his resignation, were warmly received on the street because he acknowledged the plight of the people and their legitimate concerns.”

People won’t mind a Hariri comeback, he added, if he manages to get rid of the extremely unpopular Gebran Bassil, his outgoing foreign minister, accused by the angry demonstrators of arrogance, corruption, and misuse of public office.

That would be easier said than done, however, given that Bassil is President Michel Aoun’s son-in-law and leader of the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM), which controls 29 seats in Parliament and almost half of the Christian street.

Other candidates

Najib Mikati’s name has recently resurfaced, given that he is a powerful and independent ex-premier who led the country after Hariri’s 2011 resignation.

A wealthy businessman and a native of Tripoli, he happens to be on good terms with both Saudi Arabia and Iran, the two main stakeholders in Lebanese politics, but lacks parliamentary support, with only 4 out of 128-seats in the Chamber—no match for Hariri’s bloc of 20 MPs.

The second suggestion is Tammam Salam, another former premier who held the job in 2014-2016.

Given that he has no political party behind him or any parliamentary representation, he might be fit for the transitional period, specifically because of his weakness.

More powerful players would be able to manipulate him and enforce their will, both within the Sunni community and beyond.

Some are even speculating that Raya Al Hassan, a powerful two-time minister from Hariri’s team, would be fit for the job.

“Circulating these names is just a waste of time,” said Ghassan Hajjar, managing editor of the mass circulation daily Anhhar.

“If Aoun names somebody other than Hariri, it would be political suicide and the end of his era.”

“Nobody from the Hezbollah-led March 8 Coalition would dare nominate himself against Hariri, something that President Aoun understands only too well,” he told Gulf News.

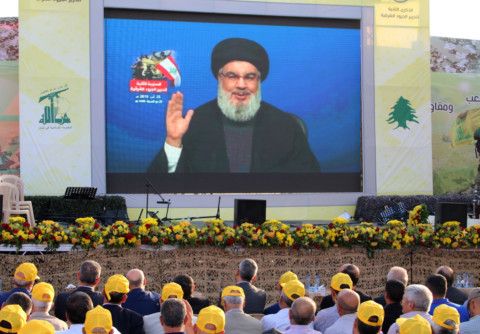

The Hezbollah Factor

Hariri’s 2016 comeback was facilitated by Hezbollah, who agreed to accept him prime minister if Hariri signed off on their ally, Aoun, as president.

“That agreement still stands,” said Akoum, “and Hezbollah might re-invest in it to bring their technocrats into any new government.”

Rejecting Hariri would plunge the country into the unknown, creating a political vacuum that might take weeks to fill—perhaps months.

“Hezbollah can always resort to a one-color government,” said Lebanese analyst Nidal Al Sabe, given that along with its allies, it currently enjoys 72 votes in Parliament.

“But that would bring serious consequences,” he said to Gulf News, “leading to an immediate confrontation with the international community, led by the United States. They would consider it a Hezbollah government and respond with sanctions on the entire executive branch.”

Any government created exclusively by Hezbollah allies will kill also whatever chance Lebanon had of receiving an international loan pledged in Paris last year, worth $11 billion USD.

That money is badly needed to revive the cash-strapped Lebanese economy, and before stepping down, Hariri said that the first stage of its implementation was expected within three-months.

The Gibran Basil dilemma

Hariri has been saying that will consider a comeback if mandated to lead a cabinet of technocrats, where ministers are appointed for their professional merit, rather than political affiliation.

That would mean a definite ouster of Bassil.

“Bassil would never accept,” explained Al Sabe, explaining: “He believes that if Hariri stays, then so should he. According to his logic, neither of them are technocrats, and both are heads of political parties with parliamentary blocs. He is conditioning that they either stay together or leave together.”

“Hezbollah is suggesting a so-called techno-political cabinet, one where service-oriented portfolios go to independent technocrats, while political posts, like foreign affairs, economy, and defense, are kept with the main political parties.”

Who controls what?

Hezbollah currently controls three portfolios in the outgoing Hariri cabinet, being parliamentary affairs, youth, and health.

The Hariri bloc controls 6 out of 30 portfolios, including information, telecommunications, and interior, while Aoun’s team holds eight, including defense, economy, presidential affairs, and foreign affairs.

According to the National Pact, a gentleman’s agreement dating back to 1943, the premiership in Lebanon must be held by a Muslim Sunni, while the presidency goes to a Maronite Christian.

Hariri has held the job twice, first being in 2009-2011 and then from 2016 until 2019. He stepped down last week, in light of massive demonstrations that broke out across Lebanon, calling for economic reforms and rehaul of the entire political system.