For Indian citizens living outside of India, determining their tax residency status is important to understand the extent to which their global incomes could be taxed in India. This article will guide you through the determination process in a step-wise approach.

For simple understanding, the tax residency status is divided into two groups namely, ‘resident’ and ‘non-resident’.

A ‘resident’ individual could be categorised either as an ‘Ordinarily’ resident or as a ‘Not Ordinarily’ resident, which is a notional categorisation based on the individual’s residency status of the last 10 years.

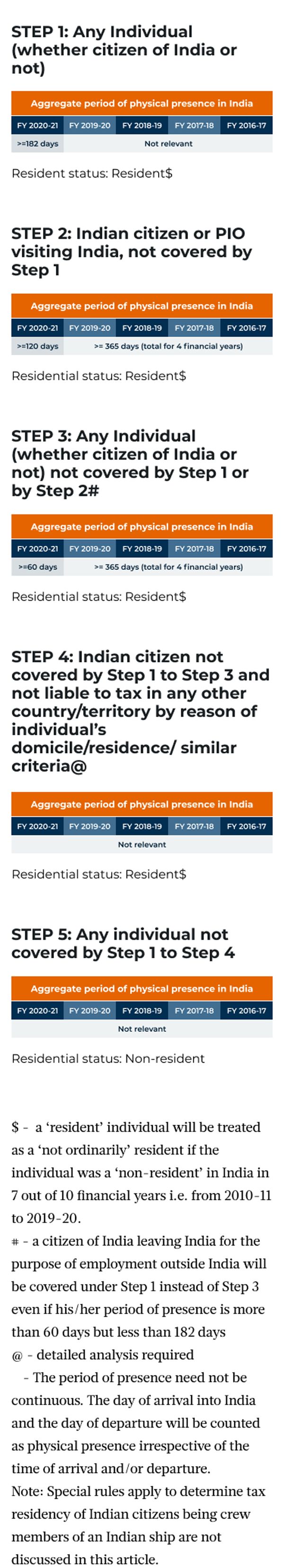

Step 1: General 182 days rule

An individual, whether an Indian citizen or not, is considered as a ‘resident’ if his/her physical presence in India in the financial year, i.e. 01 April to 31 March, aggregates to 182 days or more. This is often referred to as the ‘182 days rule’.

An individual, whether an Indian citizen or not, is considered as a ‘resident’ if his/her physical presence in India in the financial year aggregates to 182 days or more

The period of physical presence need not be continuous as the days spent in India from time to time needs to be aggregated. Further, the day of arrival in India and the day of departure will be counted as physical presence irrespective of the time of arrival and/or departure. For example, if an individual arrives in India at 11pm on 12/02/2020 and departs from India at 2am on 14/02/2020, the total days of physical presence will be three days.

Special rules apply for certain specific scenarios discussed in the following steps. However, if an individual satisfies the ‘182 days rule’, then there is no requirement to check other scenarios. The individual should directly check the category of residency under step 4 given below.

Step 2: Specific 60 days rule

Even if the ‘182 days rule’ is not satisfied, an individual, whether an Indian citizen or not, will still be considered as a ‘resident’ if the individual’s physical presence in India crosses the following two thresholds:

- The physical presence in the current financial year aggregates to 60 days or more; and

- The physical presence in the preceding four financial years aggregates to 365 days or more.

However, the following two special exceptions apply to the '60 days rule’.

Exception 1: Indian citizens or PIOs visiting India

The first exception to the ’60 days rule’ applies to Indian citizens or persons of Indian origin (PIOs) visiting India from outside India. Such individuals could visit India periodically for family visits, work, etc., exceeding 60 days in a financial year.

From financial year 2020-21, such individuals are proposed to be treated as ‘resident’ only if their physical presence in the financial year aggregates to 120 days or more and their physical presence in the preceding four financial years aggregates to 365 days or more.

Exception 2: Indian citizens leaving India for employment

The second exception to the ’60 days rule’ applies to Indian citizens leaving India for employment outside India. As such individuals may possibly receive the employment offer anytime during the year, they may have stayed over 60 days before leaving for employment.

Such individuals will be considered as ‘resident’ only if their physical presence in the financial year of leaving India aggregates to 182 days or more.

Step 3: Overarching rule for Indian citizens not liable to tax in any other country or territory

From financial year 2020-21, it has been proposed that an Indian citizen shall be deemed to be a tax resident in India ‘if the individual is not liable to tax in any other country or territory by reason of individual’s domicile or residence or any other criteria of similar nature’.

The varying interpretations of the budget proposal had initially led to a widespread confusion amongst the non-resident Indian (NRIs) working in the Middle East/Gulf region as they are not otherwise taxed in the respective Middle East countries. However, the Indian tax officials have issued a press release stating that there is no intention to tax Indian citizens who are bona fide workers in the Middle East.

However, more clarity is expected on the scope of the overarching rule.

Step 4: Type of residency

Once an individual determines that he/she is indeed a tax resident in India as per above steps, the category of residency should be determined that is whether the individual is an ‘ordinarily’ resident or ‘not ordinarily’ resident.

From financial year 2020-21 onwards, a tax-resident individual would be treated as ‘not ordinarily’ resident if the individual was a ‘non-resident’ in seven out of 10 financial years preceding the current financial year, that is from 2010-11 to 2019-20.

It is a debatable issue whether the status as ‘non-resident’ in the preceding 10 financial years should be examined as per the income tax provisions as it existed in the respective financial years or as per the provisions of the current financial year.

Having determined the correct tax residency, the scope of taxation based on the tax-residency status is as follows:

- ‘Resident (and ordinarily resident)’ are liable for tax in India on their global income

- ‘Resident (but not ordinarily resident)’ are liable for tax in India in respect of income which accrues or is received in India (or, is deemed to so accrue or received in India) and in respect of income from a business controlled in or a profession set up in India.

- ‘Non-resident’ are liable for tax in India only in respect of income which accrues or is received in India (or, is deemed to so accrue or received in India). They are not liable for tax on their global income.

An individual may seek benefits under Double Tax Avoidance Agreements between countries to ensure that the he/she is not taxed twice for the same income.

Separate rules apply to Indian citizens working as crew members of Indian ships, which are not discussed in this article. But, if you have any specific queries related to that, please feel free to comment or email us on readers@gulfnews.com.

Conclusion

With the scope of taxation increasing in the Middle East with developments around economic substance regulations (ESR), country by country reporting (CbCR) and Value Added Tax (VAT), India’s Union budget has never before raised as much interest as this year. It is becoming important for individuals as well as businesses to keep a track of tax developments and their obligations under tax laws around the world.

The writer is the Managing Director of AskPankaj tax consultants and tax agency