World leaders are finalising preparations for this week’s G20 leadership summit in Osaka, Japan. The meeting, which may yet see US-China trade tensions ease or escalate, could become the most important G20 since the 2009 event in London during the storm of the international financial crisis.

Presidents, prime ministers and heads of state will be in attendance from the United States, China, Germany, India, Japan, Indonesia, Australia, Russia, Brazil, United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Turkey, France, Italy, Germany, Canada, South Korea, Argentina, Mexico, and the EU. Collectively, these powers account for some 90 per cent of global GDP, 80 per cent of world trade, and around 66 per cent of global population.

Recent summits, especially in Hamburg in 2017, have been perhaps most memorable for the divisions within the G20 powers. Especially vis-a-vis the United States and key EU countries, over issues such as international trade, migration and climate change.

While the G20 has not yet lived up to some of the initial expectations of it, it continues to be a forum prized by its members as the session in Japan will show.

One flashpoint has been the sometime strong disagreement over global trade. In Hamburg, for instance, Angela Merkel pushed for a strong G20 re-affirmation of international trade, while Donald Trump secured language in the end-of-summit communique that countries can protect their markets with “legitimate trade-defence instruments”.

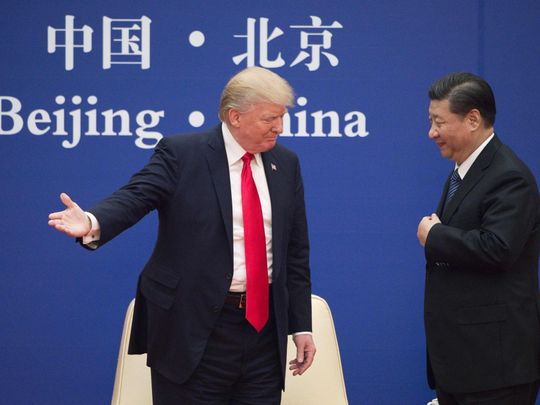

This same topic is also likely to be central to this year’s meeting narrative with Beijing and Washington having been locked, now, for well over a year in what could yet descend into a trade war with both sides having imposed hundreds of billions of pounds of tariffs. While a deal had appeared imminent in March, there has since been a frosty air in US-Sino ties with Trump accusing Beijing of “breaking the [potential] deal” because of alleged backtracking on key issues, including Chinese state subsidies.

Trump’s optimism

Trump has repeatedly expressed optimism that a breakthrough could yet be reached, and the G20 forum could be important here in at least two respects. Firstly, the two sides brokered a truce at last year’s event in Argentina, agreeing to delay imposition of further tariffs, in a move that kick started the flurry of negotiations earlier this year that gave rise to hopes of an agreement.

A second reason why the G20 could be important is that it offers a relatively rare forum for Xi Jinping and Trump to meet face-to-face. Given the importance the US president puts on such personal one-to-one interaction and summitry, it remains possible that the mood music in Japan could yet be more positive than many expect, with the outside chance of a breakthrough with Xi.

In this tricky, uncertain context one indicator of the summit’s success will be in being able to break through disagreements that do arise across the leaders and agree a powerful end-of-summit communique.

All previous G20 sessions have done so, but recent global summitry — including last year’s G7 in Canada and the Apec [Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation] meeting in Papua New Guinea — both saw unprecedented failures to agree communiques.

One other reason why the summit will be noteworthy is that it will mark the last G20 for several world leaders, including Theresa May who leaves office soon. Other leaders who may also lose power, potentially, in the next year include Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, and Merkel.

The significant amount of attention on this year’s G20 this year highlights, yet again, that the body is widely perceived since the 2008-09 financial crisis to have seized the mantle from the G7 as the premier forum for international economic cooperation and global economic governance. It is now more than a decade since the G20 was upgraded from a finance minister body to one where heads of state now meet too — a move which was greeted with considerable fanfare, including from then-French President Nicolas Sarkozy when he claimed that “the G20 foreshadows the planetary governance of the twenty-first century”.

Yet, the fact is that the forum has failed so far to realise the full scale of the ambition some thrust upon it, at the height of the international financial crisis. A key part of failure to deliver on previous high expectations is that the G20 meetings have no formal mechanisms to ensure enforcement of agreements by world leaders.

There also remains concerns by states outside the G20 about the club’s composition which was originally selected in the late 1990s by the United States along with G7 colleagues. While states were nominally selected according to criteria such as population, GDP etc, criticism has been made of omissions such as Nigeria, sometimes called the ‘giant of Africa’, which has three times South Africa’s population.

Former Norwegian foreign minister Jonas Gahr Store has gone so far to call the G20 “one of the greatest setbacks since World War Two” inasmuch as it undermines the UN’s universal sense of multilateralism. Reflecting this, the UN General Assembly convened a rival UN Conference on the Global Economic Crisis in 2009 as an alternative forum.

Taken overall, while the G20 has not yet lived up to some of the initial expectations of it, it continues to be a forum prized by its members as the session in Japan will show.

This year’s event could be especially memorable given the possibility of tensions, easing or escalating, significantly between Trump and Xi in the context of the long-running US-China trade tantrum.

— Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics