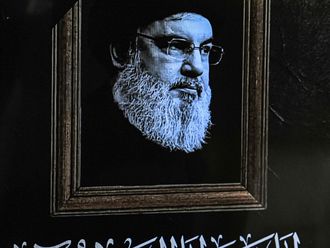

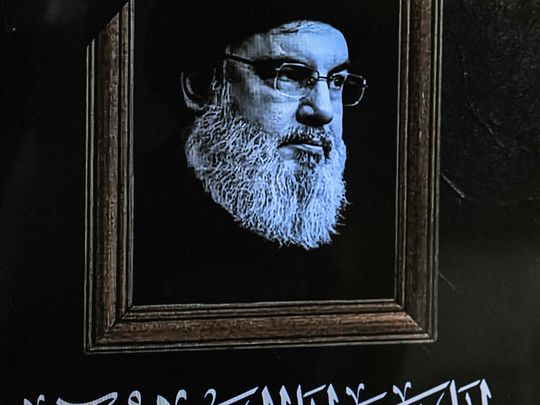

In the Middle East, where regional tensions often dominate the narrative, it’s still too early to predict the full impact of Hassan Nasrallah’s assassination and the ensuing public relations battles, similar to Iran’s response.

Iran claims it struck vital targets in Israel, while Israeli and Western sources downplay the effectiveness of the missile attack. Each side’s supporters are firmly convinced of their own version of events.

It’s a well-known saying that the first casualty in war is truth. From my recent observations of Western military analysts, I’ve learnt that anti-missile systems are costly. If the defending country (in this case, Israel) is confident that an incoming missile will land in an uninhabited area, they might choose not to intercept it.

Simply because the cost of defence would outweigh the potential damage. This might explain how an Iranian missile killed a Palestinian in Jericho, as if the Palestinians needed any more suffering, and how another missile fell in Jordan.

It’s likely that retaliation for the killing of Nasrallah and Haniyeh will involve coordinated missile strikes, intended to placate angry Iranians, Lebanese, and some Arabs. In the broader international context, the leadership can then reassure their people: “We responded as necessary.”

Campaign of coercion and intimidation

The situation on the ground tells a different story. While the missile strike may have been coordinated in terms of timing and location, it has drawn widespread condemnation from the US, UK, France, Germany, Spain, and others, who have held Iran accountable. This further isolates Iran diplomatically, even if the strike was planned.

The root of the conflict lies in Hezbollah’s activities in Lebanon, which Israel views as an Iranian proxy capable of being mobilised if Iran faces direct threats.

Hezbollah’s actions have put Iran in a difficult position, forcing it to search for an exit, even if only symbolic.

At the peak of Iran’s financial and military support, Hezbollah alienated many around it, eroding Lebanon’s long-standing political balance that thrived on compromise. It severed ties with Lebanese partners by targeting and killing numerous politicians and intellectuals, even those within its own sect.

Hezbollah also burnt bridges with Arab nations, launching harsh campaigns against them, particularly those in the Gulf, seemingly serving a different agenda. In Lebanon, intimidation became Hezbollah’s weapon of choice. Whenever it silenced opposition, it believed this strategy was effective.

However, in the era of the communication revolution, even some within Hezbollah’s circles have publicly expressed frustration with the party, only to retract their statements within hours, apologising to the leadership in a humiliating manner. This recurring pattern has become a troubling human phenomenon, but rather than addressing it, Hezbollah continues its campaign of coercion and intimidation.

Hezbollah had grown into a domestic force that many viewed as a monster with its vulnerabilities exposed, making it only a matter of time before it would be targeted, isolated, and eventually lose key figures, most notably Hassan Nasrallah.

A misreading of reality

The critical question now is whether the new leadership that takes over will learn from the harsh lessons the party and Lebanon have endured or if they will persist along the same destructive path. This question remains unanswered, with Lebanese politicians and the wider Arab region waiting, analysing, and watching closely.

To pull Lebanon out of its current crisis, four key steps are essential — none of which involve Iranian missiles. First, a unified military under the Lebanese army, with all other groups transitioning into unarmed political parties, competing under a shared national banner.

Second, the revitalisation of state institutions, from the presidency to the prime minister’s office. Third, Lebanon must be neutralised in regional conflicts. And fourth, the focus must shift to reviving the economy, which has been decimated, pushing a significant portion of the population into poverty.

These four steps are Lebanon’s path to salvation, a way out of the cycle of violence that has used its citizens as pawns in regional power struggles — struggles that have nothing to do with liberating Palestine. Lebanon’s lack of technological advancement, civil infrastructure, and internal support has left it vulnerable. Missiles, no matter their agreed course, will not save it.

While the future is uncertain and difficult to predict, one thing is clear: continuing with past policies will lead only to further ruin. The fatal miscalculation Hezbollah made was in using an excess of power domestically while suffering from a lack of power internationally — a complete misreading of reality.

Mohammad Alrumaihi is an author and Professor of Political Sociology at Kuwait University